What do feminists and anarchists have in common? What's the story behind the Squamish Five, the Wimmin's Fire Brigade and the porn shop bombings of the '80s? Burnaby resident Eryk Martin has all the answers. The SFU student is working on his PhD dissertation in history, and he's focusing on anarchism.

Jennifer Moreau: What got you interested in anarchism?

Eryk Martin: I became interested in anarchism for two reasons, really. First, anarchism came into my life through music. Punk, in particular, provided me with an accessible and creative medium to learn about political ideas. It wasn't just one band, or one song, but a slow process of soaking up radical politics through punk. Second, the anti-globalization movements of the late 1990s and early 2000s seemed, in my experience, to be awash in anarchist activism and culture. Since I was becoming interested in history at the same time as this was happening, I wanted to know where this anarchism came from. Where did it want to go? What could it tell me about the world? So I turned to history to find out.

JM: Most people imagine anarchism as lawlessness and violence. How would you define it based on your historical research?

EM: There is no simple answer to this. Broadly, anarchists are concerned with building alternative ways of living, working, and organizing human affairs. In particular, they are interested in promoting direct democracy, personal freedom balanced with the absence of coercion, and communal forms of organization that are decentralized and not based on top-down power dynamics.

Violence has a complicated place in this. Some anarchists have engaged in illegal political action, often in ways that are non-violent. In other instances, anarchists have used violence. There is also no consensus, either in anarchist or non-anarchist communities, on how we define violence. But regardless of how we define it, we can't understand anarchist tactics unless we also understand the social problems they are attempting to address.

JM: What do anarchism and feminism have in common?

EM: Anarchist and feminist ideas both become more prominent in Vancouver starting in the 1960s and 1970s. Both were active in the student and anti-war movements, so there's a certain amount of mixing because they were part of the same activist community. But they also shared common ideas, including a belief that politics should be based on direct forms of democracy.

JM: What was the relationship between anarchism and feminism in the Lower Mainland?

EM: In many instances it was transformative. Often, feminists found anarchist history and culture to be inspiring and fascinating. Others found anarchist ideas on direct action, political organization, and personal politics to be completely in line with their own experiences. As a result, the two approaches sometimes merged together. At the same time, not all feminists thought this way. Some were highly critical of certain anarchist ideas, including its critique of the state. And of course, anarchist men could be just as sexist and oppressive as non-anarchist men.

JM: Tell me a bit about the group Direct Action, also known as the Vancouver Five or the Squamish Five. What did they do?

EM: They were five anarchist activists who were involved in a range of social movements, including environmentalism, feminism, and anti-militarism. Over the course of the late 1970s and early 1980s they decided that social movements could benefit from an armed component. It's important to note that they expressly rejected using violence against human beings. Instead, they advocated a program of industrial sabotage that would, in their view, contest, slow down, or halt specific projects.

In 1982 they bombed a B.C. Hydro power station on Vancouver Island over concerns that it was going to lead to harmful patterns of environmental degradation, both locally and globally. They also bombed a Toronto factory that was producing parts for American nuclear weapons. It's also important to see these actions as part of a much wider pattern of dissent. Other environmental and anti-nuclear movements had tried for years to fight against these issues but had failed to gain significant change. As a result, Direct Action (the Vancouver Five) felt that legal options had run their course, and that popular protest needed to be augmented with radical action.

JM: The two women from the Squamish Five were also involved in the Wimmin's Fire Brigade, which was responsible for fire-bombing porn shops around the Lower Mainland. Can you tell me a bit about what they did and why?

EM: In the early 1980s, a number of different women's groups began organizing against the pornography retailer Red Hot Video. These stores, and others like them, stocked extremely violent pornographic films. Activists argued that these films were not only illegal under the Criminal Code, but that they also encouraged men to equate sex with violence. When the government refused to take meaningful action against the stores, the Wimmin's Fire Brigade decided to do it themselves.

JM: In a post-911 era, we'd be quick to call that terrorism, but what was the public's attitude at the time.

EM: In our current political climate it's easy to imagine that public commentary would uniformly dismiss these actions. And certainly, in 1982, there were many people who did. But what I've seen through my research is that there was a vigorous middle ground where people were able to voice a complex and diverse array of opinions on the issues and the tactics. This was most prominent in the case of the Red Hot Video and B.C. Hydro actions.

JM: Did any of these people do jail time?

EM: Yes, all of the Vancouver/Squamish Five were convicted and they spent many years in jail.

JM: Was anyone ever physically hurt by their actions?

EM: Yes. Despite being opposed to targeting people, the bomb that Direct Action placed in Toronto detonated earlier than it was scheduled to, probably because of some technical malfunction. At this point, the evacuation of the factory was still under way. Several people were seriously hurt. Although no one was killed, it was a devastating experience for many.

JM: What do you think of the Wimmin's Fire Brigade and the Squamish Five's choice of tactics?

EM: If we are willing to take them seriously, if we're willing to put them into the broader political, social, and cultural context of their time, then I think they can help us to see that movements that use radical tactics are often much more complicated than we might otherwise suspect.

JM: Gerry Hannah, a member of the Subhumans, was part of the Squamish Five, and he grew up in Burnaby. Are you aware of any other local connections to the anarchist movement of yesteryear?

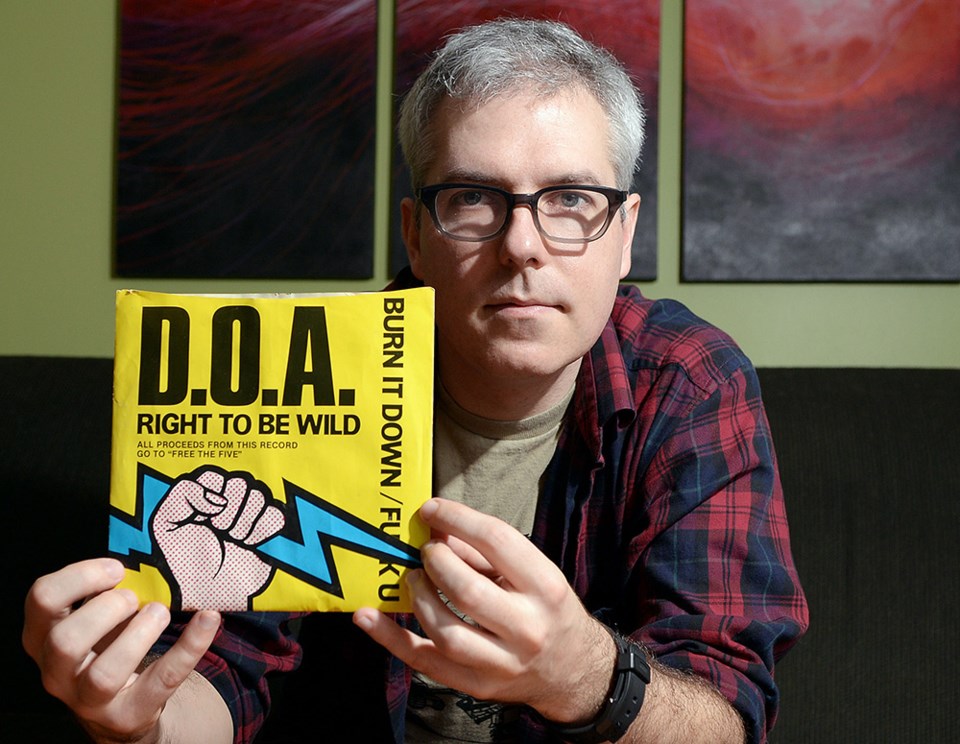

EM: Punk is one of Burnaby's main contributions to anarchist politics and culture during the 1970s and 1980s. And it went beyond individuals such as Hannah. Both the Subhumans and D.O.A. had members from Burnaby, and had close connections to a wide range of anarchist projects in the Lower Mainland. In particular, anarchist activists and musicians from the punk community came together to organize a series of "Rock Against" concerts that raised awareness over issues including racism, nuclear weapons, and deplorable conditions in Canadian prisons.

(Editor's note: Joe Keithley does not identify as an anarchist.)

JM: What lesson can we take away from this history you've examined?

EM: That anarchist activism, be it legal or illegal, has been a critical part of British Columbia's history. But the only way to understand this history is by taking radical politics seriously. You don't have to agree with what these people did or thought, but if you're going to understand these movements, you must be willing to listen to what they have to say.

JM: How do you feel as a man giving talks on "herstory"? Is anyone giving you flack for that?

EM: No one has ever given me flack for being a man and writing about the history of women's activism. I think it's important for men who are historians to think and write about women's lives, as well the lives of other people who do not identify as either men or women. If our job as historians is to make sense of the past, how can we do that if the men in our profession only think and write about the lives of other men, and ignore everyone else? The feminist in me sees that as unjust. As a historian, it seems like bad practice.

JM: Do you have any plans to turn your dissertation into a book? If not, where can the public find out more about your research?

EM: Yes, I'm certainly planning on turning the dissertation into a book. I also have an article coming out this spring in the journal Labour/Le Travail that talks about the relationship between anarchism and punk in Vancouver during the 1970s and 1980s.