In September 2014, five-year-old Amber headed off to kindergarten at Burnaby’s Brentwood Park Elementary with a secret – her father.

He had gone underground a few months earlier to avoid a deportation order that threatened to split up the family and send him back to South America after 45 years in Canada.

He continued to live with Amber, her little brother and her mom, but Amber knew she couldn’t talk about him at school.

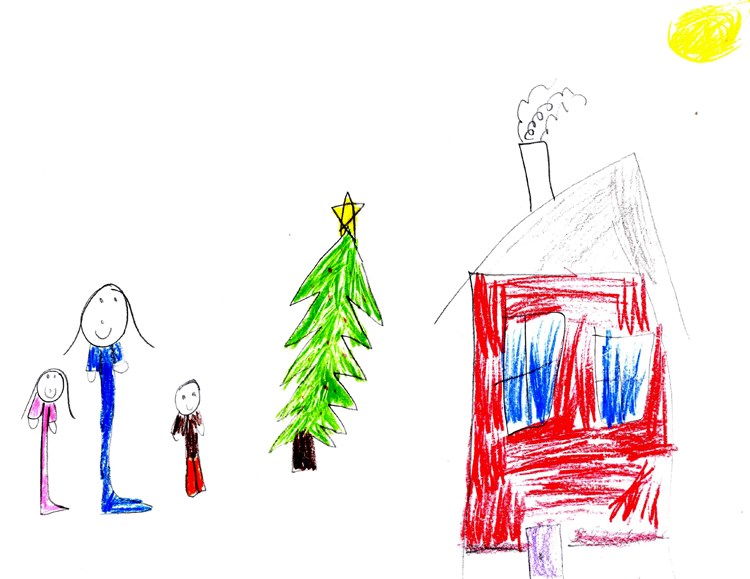

So when it came time to draw family pictures at school, Amber drew everyone but him.

“There was a lot of heartbreaking times,” said her mom, Trish, who asked that the family’s last name not be used.

Sending Amber to school at all was a risk, Trish said, and the family considered homeschooling, but Trish eventually decided to pose as a single mom at the Burnaby school instead.

“I was always hypervigilant, having to bring her to school, worried if somebody might be waiting there, worried that somebody would follow me home, worried if my daughter would say something at school that didn’t match what they had on file,” Trish said.

When her mom got sick, Amber stayed home because there was no one else to take her to school.

“We didn’t want to take the risk of separation by her dad showing up at the school for things,” Trish said.

Not the only one

Local teachers say Amber isn’t the only child in Burnaby whose education has been affected by her family’s immigration status, and the Burnaby Teachers’ Association (BTA) wants the school board to adopt a policy that would make accessing education easier and less frightening for families like hers.

Last month, the teachers’ union invited trustees, the district parent advisory council and local immigrant rights activist Harsha Walia to a meeting to discuss a possible so-called “sanctuary schools” policy.

“What was identified is that, although there was no instances of staff being aware that any student has been turned away, the concern was that’s because parents aren’t sending them in the first place to register because of the fear of being discovered with less than legal status,” said trustee Gary Wong, chair of the board’s policy committee.

The Toronto District School Board was the first in Canada to pass a sanctuary schools policy in 2007 after public protest over Canada Border Services Agency detaining Toronto students to flush out parents who didn’t have legal status in Canada.

The Toronto policy now guarantees all students admission regardless of immigration status and states information about them or their families will not be shared with immigration authorities.

The B.C. Teachers’ Federation crafted a similar policy in 2014 and is encouraging teachers to work with their school boards to use it as a template for their own policies.

Wong said such a policy makes sense and children shouldn’t be denied an education because of their parents’ immigration status.

But he said B.C.’s education law is different from Ontario’s and that could pose an obstacle to a policy that calls on schools to admit students without legal status and to withhold information about students and their families from immigration officials.

“Since 1993, Ontario’s Education Act specifically provides for admitting children without legal immigration status whereas B.C’s School Act is silent,” Wong said.

But Walia, co-founder of the Vancouver chapter of No One is Illegal, said B.C. education law poses no obstacle to a sanctuary schools policy because it is silent on immigration status.

“There’s nothing in the law that says non-status students don’t have a right to education in B.C. It’s just that there’s nothing proactively ensuring that that happens,” she said.

Too many questions

Fear is the biggest obstacle keeping students from families with unresolved immigration issues from accessing schools, Walia said, and a policy is needed to reassure them schools are safe.

She said schools currently exacerbate fears by asking for a lot of unnecessary paperwork.

“A lot of schools, when you don’t have the birth certificate of the student, then definitely they ask for a lot for immigration papers, passports, things like that,” she said.

A sanctuary schools policy would require the district to hammer out exactly what questions need to be asked and which don’t for kids to be registered at local schools, said Burnaby Teachers’ Association president Rae Figursky.

“… some people come to this country very concerned about any question being asked, and we need to make sure that we’re asking only the ones we really need to and that every student in Burnaby has that access to education,” she said.

Besides lobbying the local school board, the BTA is also urging the BCTF to lobby the provincial government to adopt a provincewide sanctuary schools policy.

“It would be nice if it was the whole province, but in the meantime we’re also approaching our trustees to take a look,” Figursky said.

But a local policy has “a ways to go,” according to trustee Wong, who brought the idea up at a recent policy committee meeting, where further information was requested for future discussion.

New beginning

Amber, meanwhile, left the Burnaby school district last spring.

Citizenship and Immigration Canada has since accepted her dad’s permanent residency application on humanitarian and compassionate grounds, and he attended his first parent-teacher conference at Amber’s new Surrey school in December.

“It’s just been such a relief,” said mom Trish. “It’s just sort of lifted this weight off of us and off of the whole situation surrounding schooling. He’s pretty pleased to be a part of bringing her to school, signing her planner and filling out things that come home that need to be signed. It’s kind of like she’s just starting school for him.”