NEW YORK (AP) — Could it really be true? That of all of college basketball’s urban myths, one of New York’s five boroughs is actually the birthplace of filling out an NCAA Tournament bracket?

Before all those office pools truly defined March, betting the bracket was the supposed brainchild of an Irish pub owner in Staten Island — a “creative businessman,” his son calls him — whose straightforward idea of plunking down 10 bucks to pick the Final Four teams and the national champion turned the unassuming spot into a bustling attraction where the special of the day could be a million-dollar payout.

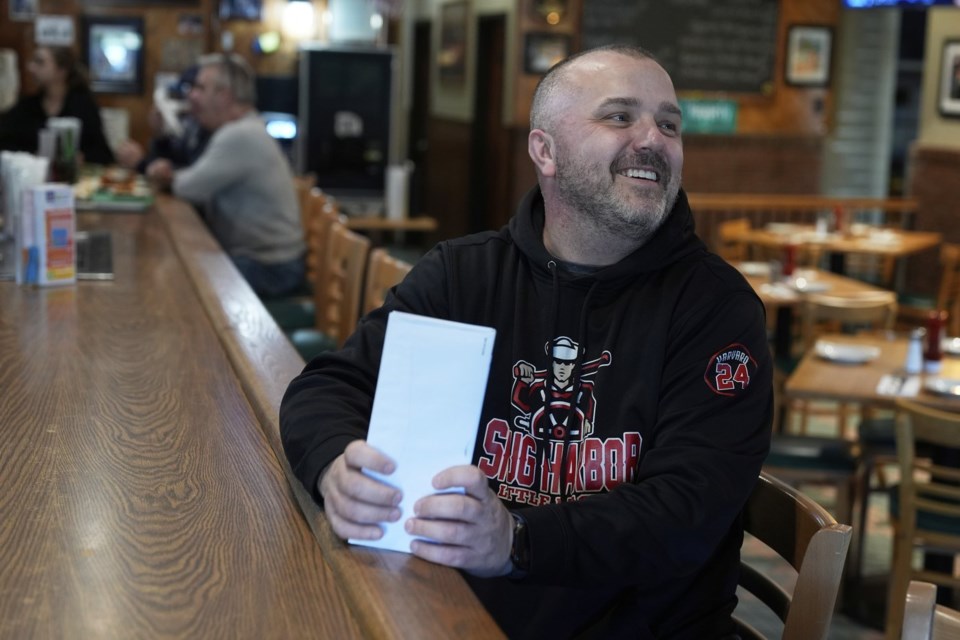

“We created a pool that just blew up over time,” current bar owner Terence Haggerty said. “Looking back at it now, how did we pull it off? How did we do it? It was crazy.”

Through the decades of Larry and Magic, of Jordan and Laettner, through word of mouth and an embarrassment of riches, the contest took off — so much so that the West Brighton neighborhood favorite, Jody’s Club Forest, stakes its claim (though not without at least one other contender to the crown) as the bar that helped ignite the bracket into a billion-dollar business.

Haggerty’s parents, Mary and Jody, opened the club in 1976, and by the next college basketball season, already had hatched the idea of running a college basketball pool to boost business. The rules were simple: Pay $10 to pick only the Final Four teams, the national champ and total points as a tiebreaker in a winner-take-all format. The tournament field of 32 teams — no need to fill a line for every round — was dwarfed by the 88 total entries, with the winner netting $880.

By the time Jody’s Club shut down the pool in 2006, under scrutiny from everyone from the IRS to Sports Illustrated, the jackpot was a whopping $1.6 million to the winner.

“We never in a million years would have ever imagined where it got,” Terence Haggerty said.

Kentucky contender

Every March needs a Cinderella, and Jody’s Forest Club can punch its ticket as an originator in gambling-related contests.

But in the home of bourbon, basketball and the Louisville Slugger, could the idea of penciling in a winner for every line have taken its first swing in 1970s Kentucky?

Bob Stinson, who died at 68 in 2018, was a U.S. Postal Service worker who applied the idea of using his recreational softball league bracket and the furor over Kentucky Derby betting slips to create his own bracket for the 1978 NCAA Tournament.

“My dad just thought it would be fun to fill out the brackets,” said his son, Damon Stinson. “It was kind of a betting thing but not really. It was kind of a who-knows-college-basketball-better kind of thing.”

Stinson said his father used a ruler and unlined paper to sketch out brackets and required only a nominal entry fee. The winner earned more bragging rights than a life-changing bonanza, though that was just fine with Bob Stinson, who traveled around the country for his job and brought brackets with him every March.

“He was proud of it,” Damon Stinson said. “Instead of just watching the games, let’s fill this out. He self-promoted the idea. He was tech savvy back in the day. So when Excel came out, the first thing my dad did was build a tournament bracket off it. This was perfect. He really had the first bracket pool electronically that anybody had, and he emailed it to everybody. That’s how it grew into a much bigger pool and things got out of hand.”

Damon Stinson says he once almost got thrown out of Catholic school for peddling brackets to other students for $10 each and was caught with $350 and a “bunch of brackets in my backpack.”

Trying to prove the real inventor of the March Madness pool seems as implausible as, well, picking a perfect bracket.

Stinson said his father truly believed he made the first one.

“Yes, 100%. Because he traveled for work, nobody had seen what he was doing,” Stinson said. “He traveled a lot nationally around the same time he was coming up with the idea and spreading it. He truly believed. The true 1-64, we’re going to write them down, we’re going to go round-by-round, that literal format is what he started with.”

Hoop dreams

There is not a shred of acknowledgment at Jody’s Club that it was ever a hub for basketball bets. No banner outside, no photos of past winners or framed snapshots of winning tickets. The decor is mostly an homage to Haggerty’s parents, who raised their kids about 12 blocks away.

Haggerty conceded there’s no real proof the bar was the first spot to run an organized pool.

“If somebody said, ‘No, it’s mine,’ go right ahead,” Haggerty said. “Look around here. It’s not something we really promote. It’s not how we were. It’s not how my father was. It’s definitely not how my mother was. If I celebrated that, I wouldn’t feel right doing it.”

Haggerty has no record of ticket winners — not even of the $1.6 million jackpot — but on a recent trip to the pub, a past champion had a barstool seat, a pint and a pining for his share of a six-figure payout won in 2003. Jack Driscoll said he played nearly every year during the life of the pool and recalled the thrill of placing that first bet each March.

“The cutoff day for submitting tickets was as big as any other holiday around here,” he said.

Driscoll struck it big when Syracuse won the national championship. He used the windfall to invest in home improvements, notably a new kitchen.

The real March Madness at Jody’s Club was figuring out where to stuff piles and piles of cash. No ordinary cash register would hold the hundreds, then thousands, and — twice! — millions wagered in the pool. The family once asked a nun to hold a hefty wad of collections.

“It was sprinkled here, sprinkled there, a little bit of everywhere,” Haggerty said. “Banks. It was hidden in houses at some point. It was quite the operation.”

The pool was essentially a mom-and-pop business, and it took days in its beginning in an era without fast and reliable computers to enter all the picks. The lines to buy a ticket — firefighters, police officers, elected officials and even Mike and the Mad Dog, Haggerty said — snaked down the street. Haggerty said ticket collection was forced into a neighboring dry cleaner and even other local bars to ease the congestion and give everyone a fair shot at playing.

“It was the best week of the year,” Haggerty said.

End of the pool

The jackpot swelled to about $997,000 in 2004 and topped $1.2 million the following year — again, much like in that first 1977 pool, the entry fee remained $10, cash only — before it stretched to 166,000 entries and a $1.6 million prize in 2006.

Thanks in large part to the swelling media attention, the numbers raised a red flag in the federal government. After the winner supposedly claimed the winnings on a tax form, the IRS came knocking on Jody’s Club door. The bar was in the clear for the pool — no one skimmed off the top, and the bar never profited from the seasonal business — but the IRS found Jody Haggerty had underreported his income over three years. Haggerty pleaded guilty to tax-evasion charges, received probation and was forced to pay restitution.

The charges were the fatal blow to Jody’s slice of March Madness.

Embarrassed by the notoriety, Jody Haggerty shut down the pool for good ahead of the 2007 tournament. He died in 2016 without another March bet placed in the pub.

“Part of it killed my father, I felt like,” the 42-year-old Terence Haggerty said of the investigation. “My father was really never the same after it.”

Even after his mother’s death in 2019, Haggerty never had any serious thoughts of restarting the pool.

“What we were put through was horrible,” Haggerty said. “But if I did it, I think it would skyrocket right away.”

Jody’s Club Forest remains a destination each March for basketball junkies who know of the bars’ role — was it really the first? Does it even matter? — in making betting pools and the art of bracketology an integral part of March Madness.

“We started something that nobody’s come close to since,” Haggerty said.

___

AP March Madness bracket: https://apnews.com/hub/ncaa-mens-bracket and coverage: https://apnews.com/hub/march-madness Get poll alerts and updates on the AP Top 25 throughout the season. Sign up here.

Dan Gelston, The Associated Press