Prince George veterinarian technician Kristie Waddell is heading back to the Northwest Territories communities of Fort Liard and Wrigley, providing care on behalf of Veterinarians Without Borders.

“They actually called and requested me to come back, so I felt very honoured that they had confidence in me to join them again on another tour,” she said, with the December tour planned for eight days.

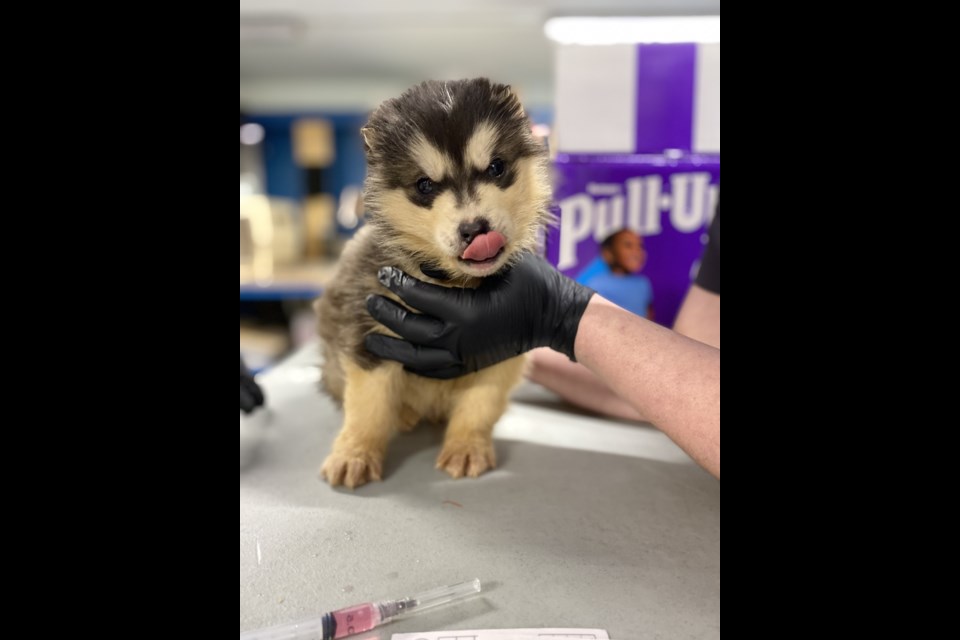

Waddell was invited to participate in their 2023 spring clinics in May, joining a team of vets and support workers, providing much needed care such as spaying and neutering, physical exams, vaccinations, in addition to some quality of life care for animals with chronic conditions.

In Yellowknife, Waddell visited Łutsel K'e, a homeland of the Dene people, before spending some time in Nunavut’s Kugluktuk, an Inuit community.

It’s been a great experience to meet fellow veterinary professionals from across Canada, says Waddell, forming friendships over the short course of the work.

“I love animals, so meeting all the variety of animals and their owners, just having an opportunity to see a different way of life and learn about indigenous values and culture, and how they love their animals so much,” added Waddell of her first visit. “They really want what’s best for them.”

The clinics bring all their own gear, and travel with the supplies they need to help the communities they visit, explained Waddell.

Most pet owners in the far north have dogs, both as companions and for practical reasons, but Waddell did treat some house cats, which are kept indoors from the cold. She also examined a pet rabbit.

“It’s not all just husky-type breeds, you’d be surprised, there were smaller dogs, some Shih Tzus, and a whole group of pugs in one family, and almost anything in-between,” added Waddell, noting most of the larger dogs are suited for the colder climate.

The organization runs clinics through their Northern Animal Health Initiative, and Waddell says the reality is that many communities in the remote North, especially Nunavut, simply don’t have veterinarians available year-round.

“Any veterinary care that they receive is coming in from elsewhere and generally only once a year from our teams,” said Waddell. “And so we work with the community, and certain individuals who are interested can be trained as community animal health workers.”