Scorching temperatures. Erratic rainfall. Drought.

These are the prevailing summer conditions British Columbia is expected to face more of in the coming decades. The changes in climate are expected to drive an exodus of wildlife seeking refuge up mountains and further north.

But for trees — which often rely on gravity, wind and water to spread their seeds — the changes in climate are often coming too fast to get out of the way, especially when combined with pressures from logging, said Suzanne Simard, a professor in the University of British Columbia’s Faculty of Forestry.

“The vast majority of seeds fall within a couple-hundred metres of the parent tree,” Simard said. “The ability to move … It’s pretty limited.”

That is, unless, they get a little help from people.

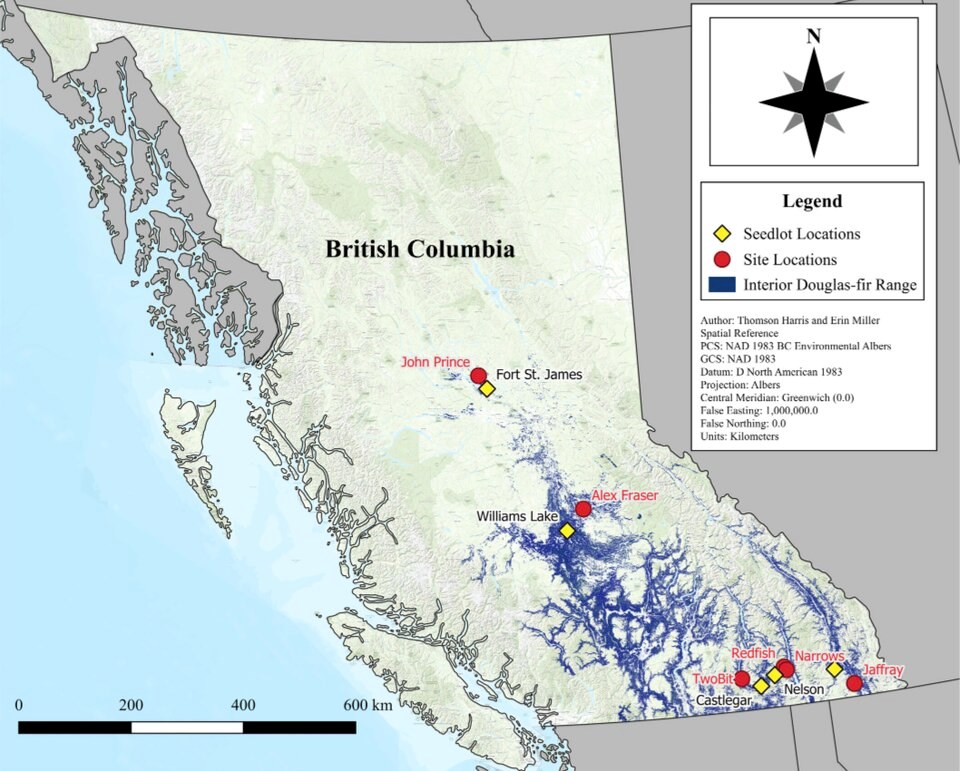

In a new study published in the journal Global Change Biology, Simard and her UBC colleagues took three-year-old interior Douglas fir seedlings from locations in southern B.C. and planted them hundreds of kilometres away, as far north as Fort St. James, the northern limit of the species’ range.

The goal of the experiment was to find out how the trees would handle the human-assisted migration, and if they would do better in a colder climate.

Simard, who oversaw the research, said they also wanted to learn how logging practices could be adapted to ensure the newly arrived trees took root.

Without a canopy of older trees, or overstory, to protect seedlings, clearcut forests can be very dry, hot places in the summer, and devoid of protection from frost in the winter, said Simard.

“We actually expected that the overstory canopy would be helpful to protect seedlings against climatic extremes,” said Simard. “It’s like having a blanket on at night.”

To test that hypothesis, the researchers planted the seedlings in logged forests ranging from completely clearcut areas to zones with 10, 30 and 60 per cent of trees left standing. The big trees tended to range from 100 to 150 years old.

The study found seedlings were indeed most vulnerable to climate extremes in clearcuts.

In drier areas prone to frost and drought, leaving 30 to 60 per cent of the old canopy behind was found to be the best way to help the seedlings recover. In more productive, wetter areas, seedling benefited when as little as 30 per cent of old canopies were left intact.

The results suggest Douglas fir seedlings will survive assisted migration better if they are planted in an intact ecosystem where they have protection, nutrients, water and good compatible neighbours, said Simard.

“Those migrants need a lovely place to land. They need protection from the older trees,” said the researcher. “We expected them to have a protective effect, and we found out that they do.”

Simard said their findings offer a warning at a time many forest ecosystems are already under stress across B.C.

In her hometown of Nelson, Simard said cedar and Douglas fir trees are still showing signs of reduced productivity since the 2021 heat dome.

“Douglas fir does really well when there’s a good snowpack,” she said. “There are basically no snowpacks in the lower elevations right now.”

Other studies have already shown that drought in the American West has led to tree mortality. And while signs of climate stress have already emerged in B.C., Simard said the province remains a “little bit behind” forests to the south.

Dying forests squeezed by climate change could lead to a great deal of carbon emitted to the atmosphere. It could also lead to a loss of biodiversity if many animals and plants face mortality before they can move.

“It’s quite scary,” Simard said. “We’ll see loss of biodiversity, and we’ll see loss of carbon pools, and all of that doesn’t bode well for trying to mitigate climate change.”

The UBC researcher is not the only one who has been warning about a potential shrinking in the range of native forests.

As early as 2006, University of Alberta researcher Andreas Hamann published a study that concluded climate change could push the range of B.C.’s tree species north at a rate of 100 kilometres per decade.

Within the coming decades, boreal and sub-boreal ecosystems could be largely pushed out of B.C. and replaced by a combination of hemlock, ponderosa pine and Douglas fir, according to the study published in the journal Ecology.

“If currently observed climate trends continue or accelerate, major changes to management of natural resources will become necessary,” Hamann concluded at the time.

In an interview this week, Hamann said the kind of research Simard and her colleagues carried out has been gaining more attention in recent years.

“There is a good rationale for assisted migration,” he said. “You have a forest that burns down. Now you have to pick a species that fits that ecosystem.”

An emerging push to adapt forests to climate change

To make that process easier, Hamann has helped develop an online seed-selection tool that allows planners to source their seeds for the current climate and for experimental test plantations targeting projected climates in the 2050s and 2080s.

Results from one forest management area Hamann is working on near Quesnel suggest Douglas fir could still have a future in the 2080s, but seeds would increasingly need to be sourced from forests farther south in Idaho or Montana.

Others, like the Canada-wide “Diverse” project launched last year, are working with the logging industry and provincial governments to test new approaches to forestry under a changing climate at 22 sites across the country.

For Simard, her team’s latest findings suggest picking the right seeds and planting in colder climates will only be successful if paired with harvesting strategies that leave ecosystems at least partially intact.

“It’s got to be done slowly and carefully,” said Simard. “It’s not like a mass migration of trees.”