Seven B.C. communities will soon have a way to gauge how tsunamis, earthquakes and the fallout from climate change are putting their families at risk — and like many things these days, it comes in the form of an app.

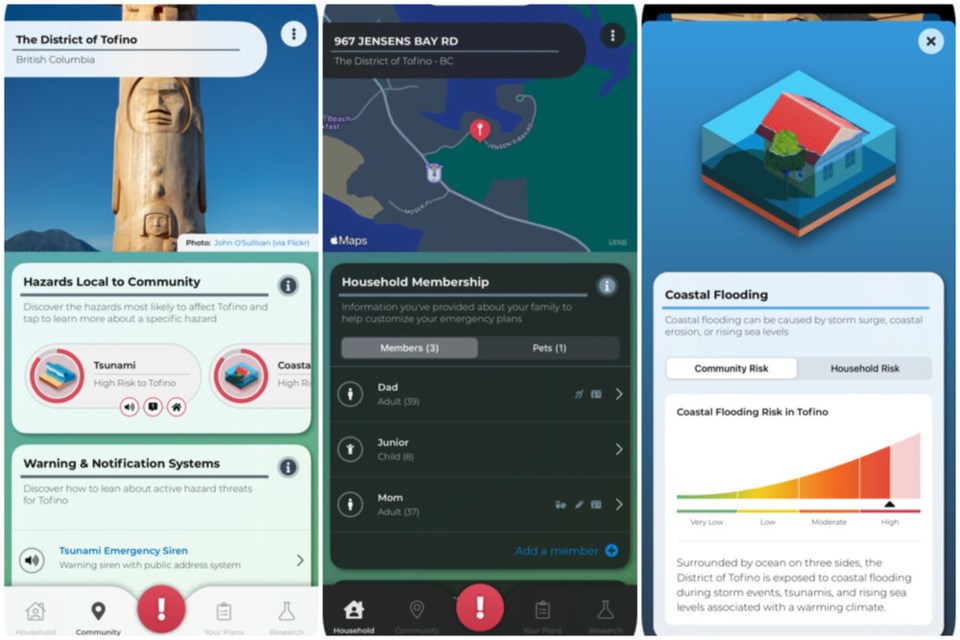

Starting in the next week or two, the Canadian Hazards Emergency Response and Preparedness mobile app (CHERP) will allow roughly 150,000 residents of Vancouver Island to identify potential natural hazards threatening their homes. The app will prompt residents to input data on family members, and then create a custom household emergency plan if things go catastrophically wrong.

“If we have someone in a wheelchair or we have pets, or we have young children, our plans automatically manage it and then update that as people age,” says Ryan Reynolds (not to be confused with the Vancouver actor of Marvel fame), a researcher at the University of British Columbia who led CHERP’s development.

In the event of an actual emergency, anyone with the app will receive tailored guidance on what to do.

So far, the communities of Tahsis, Tofino, Parksville, Qualicum Beach, Nanaimo and Oak Bay have agreed to take part in the pilot project.

“They represent a vast swath of what communities look like in Canada and B.C.,” Reynolds says.

Emergency situations range from blizzards, road closures and power outages to wildfires, a massive earthquake, tsunamis and — as the project looks to expand across Canada — hurricanes, tornadoes and avalanches.

Other disasters already built into the app include releases of hazardous materials, extreme heat and cold, landslides and overland flooding.

Reynolds says he identified a gap in people's disaster planning while researching tsunami risks in the town of Port Alberni. He found residents were confused by hazard maps, and many didn’t recognize they lived in high-risk zones.

“We're not always good at reading maps. We're not always good at understanding where those risks exist in three-dimensional space,” he tells Glacier Media.

The app pulls together a huge amount of information on disaster preparedness, that would otherwise be scattered across multiple levels of government and organizations like the Red Cross or the Canadian National Institute for the Blind.

They all provide a little piece of a very large puzzle, as Reynolds puts it. The more complex a family, the longer it currently takes to hunt through all the pieces of information meant to keep people safe.

“We want to help remove that so that people are getting right to the actual preparedness,” says the researcher, who piloted something similar in Port Alberni with positive results.

Evidence from a number of disasters shows friends and neighbours are often the most effective first responders, whether it’s carrying out early rescue work, providing first aid, bringing injured to hospital, or getting people proper food and shelter. But planning for disaster is also not inevitable.

A recent survey of Hurricane Sandy survivors in several U.S. states found those who had installed window protections and had electric generators recovered from the disaster quicker than those who didn’t. Households who understood the risks before the storm tended to prepare more, noted the study, but how much money a family made limited their ability to prepare for disaster.

The study, led by a researcher from the University of Notre Dame and published in March 2021, suggested governments could help close this gap by offering discounts on insurance premiums or generators.

Another study surveying Houston, Texas, residents recovering from Hurricane Harvey, found similar results: people who prepared for flooding before the disaster — such as installing interior drainage systems and building flood walls — experienced fewer physical health problems, lower post-traumatic stress and faster recovery.

Reynolds says researchers have also found the same patterns in Christchurch, New Zealand, after a major earthquake rocked the city in 2011, killing 185 people.

“So basically, the more prepared you are, the less time it takes to get going on that recovery process and the quicker it ends up being,” he says.

Using technology to bridge gaps in disaster preparedness has also been shown to work. In California, a pathbreaking smartphone app was developed to plan escape routes from wildfire. And during Hurricane Harvey, a geolocation app helped first responders rescue at least 25,000 flood victims, while another ensured tuberculosis patients took their medicine on time.

CHERP builds on the lessons of past disasters and the successes such pioneering technology had in helping people when they needed it most. But with funding for at least five years, the B.C.-built app is meant to act as a tool over the long term.

There are some barriers. Beyond being limited to seven communities, the app currently only works on iOS devices, but Reynolds says his team is working to make it compatible for Android. Like any app, people will need access to the internet to download and set it up. But once a user adds all their up-to-date information, it will continue to provide guidance offline.

If a user lives in a zone prone to wildfire, for example, the app will guide a family on what steps it can take to fire-proof their home, such as removing nearby brush or trees, or changing the siding to something that can resist drifting embers. CHERP will also provide information on how wildfire risk is growing as the climate crisis deepens, and what other options are out there.

Emergencies can quickly change the situation on the ground. An app-recommended evacuation route may be wiped out by floods or blocked by downed power lines.

In that case, says Reynolds, “follow the instructions from local officials. That takes the priority over anything within the app.”

The app will also update as new data clarifies who is most at risk, says Reynolds. Take flooding: roughly 500,000 homes are predicted to be in high-risk flood zones across Canada — either because of sea level rise or rivers swollen by increased rainfall brought on by the climate crisis.

None of those homes show up on national flood maps, which are currently 20 to 25 years out of date. When those maps are brought up to date (expected roughly three years from now), CHERP will receive an update. It will then show a family how flooding could be made worse from some confluence of sea level rise, extreme rainfall, coastal erosion, storm surge or a tsunami.

Reynolds and his team are looking at getting more backing from all levels of government so they can expand to communities across Canada.

“We do have interest from the Metro Vancouver area, interest from the Capital Region on Vancouver Island… but we haven't brought it to the East Coast yet. So we're going to see how this works locally. Our long-term goal is to be sure that we're including Indigenous communities.”

For that to happen, Reynolds says his team needs to show that there's demand in communities across the country. The researcher urges any local leaders interested in taking part to contact him at [email protected].

Stefan Labbé is a solutions journalist. That means he covers how people are responding to problems linked to climate change — from housing to energy and everything in between. Have a story idea? Get in touch. Email [email protected].