When Chris Harley approached the rugged coastline off West Vancouver’s Lighthouse Park, all he remembers was the smell.

“The shoreline was already dead,” he said.

Swathes of barnacles and sea stars lay baking in the sun. The dark blue and purple mussel shells that help underpin a concentrated intertidal life-support system had split open — nearly everything dead.

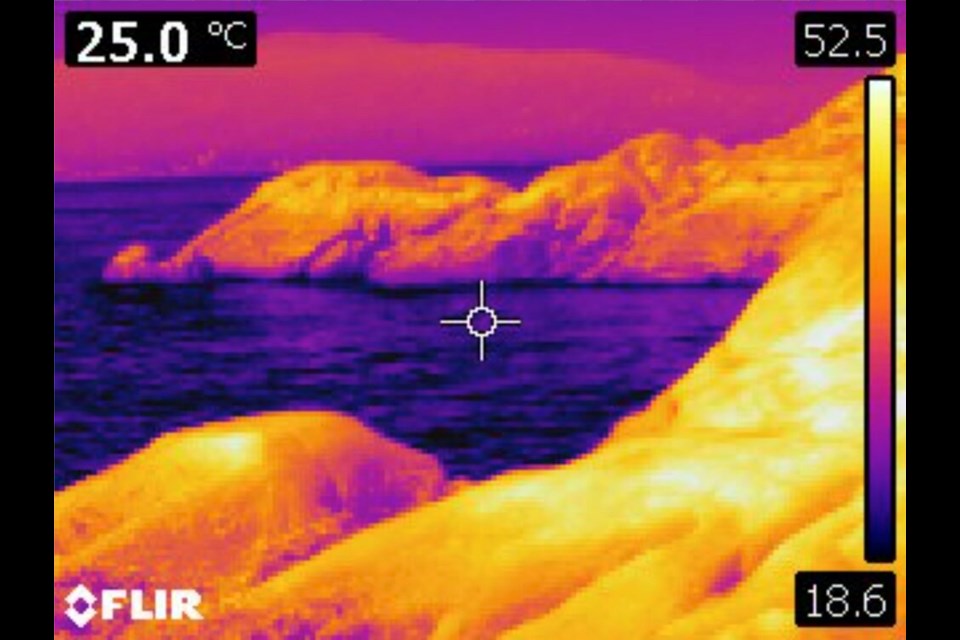

Under the June 2021 heat dome, air temperatures recorded at the nearby lighthouse had climbed to 35 C. But when the ecologist from the University of British Columbia’s department of zoology turned his thermal cameras onto the shoreline rocks, the readings shot up to 56 C, far beyond the limit of the shellfish that call them home.

In the coming days, Harley would visit beaches across the region, in White Rock and Porteau Cove between Vancouver and Squamish. On Galiano Island, he found one tennis court-size patch of rocky coastline where at least one million mussels lay dead.

Other scientists and local residents in the northern reaches of the Strait of Georgia sent him random shoreline surveys. The results all pointed to the same thing: a mass die-off.

In the end, Harley calculated the heat wave led to the death of at least one billion sea creatures across the Strait of Georgia and Puget Sound.

“I think that's a pretty healthy underestimate. I would say it’s probably 10 times that much,” Harley recently told Glacier Media.

The space between high and low tide is one of the richest concentrations of life on the coastlines of the Pacific Northwest. Here a myriad of seagrasses and small creatures create an ecosystem and feeding ground for everything from blue herons and crabs to otters and snails. It even provides shelter at high tide for migrating salmon.

In the nine months since the heat dome, Harley joined a group of researchers desperately trying to assess if the death of so many bottom-rung species would change the balance of the ecosystem.

When he returned to the shorelines around Victoria — at 10 Mile Point, Saxe Point, and all the way down to Sooke — Harley saw a remarkable return.

“They looked pretty normal to me,” he said.

But when he returned to the beaches at White Rock, around the Burrard Inlet, and in Howe Sound, the desolation was clear.

“The bad news is recovery is definitely far from complete,” he said. “The spot in Kitsilano here in Vancouver with downtown in the background last year was all seaweeds and mussels in this big boulder field and now it's bare rock and barnacles.”

The fact that the barnacles have returned is a “silver lining,” he said, as they can make it easier for other species of animal and plant life to return too.

Over the next two or three years, Harley says he hopes the ecosystem will start to return to its old self. Long term, he’s less certain.

“The questions are: how often is that sort of thing going to happen? How severe is it going to be?” he said.

According to one study, a similar powerful heat wave could once again hit the coast as early as the 2040s and return every five to 10 years.

One of the effects of the die-off is that Pacific oysters are expected to gain a foothold. Originally, catching a ride on ships from East Asia over 100 years ago, the oysters were already expected to expand their range and density as ocean temperatures warm due to human-driven climate change. The heat wave, worries Harley, will only accelerate that transformation.

“Things die back, that makes way for oysters,” he said. “I think our system is going to turn into this strange stew of things that we're used to, and things would have shown up from across the ocean that just evolved in a warmer climate.”

In other words, he says, B.C.’s shorelines could increasingly look like the subtropical ecosystems of Southern Japan, Korea and China.

Die-off a warning of things to come

It’s not just atmospheric heat waves that threaten life in and near the sea.

Direct human impacts, like overfishing, pollution and habitat destruction, all endanger species across the world’s coasts and deep ocean habitats.

But so do climate-driven ocean warming and the depletion of marine oxygen levels.

This year alone, researchers have warned ocean heat waves like ‘the Blob’ could threaten the carbon-sucking power of the Pacific Ocean and wipe out half of the Pacific’s wild salmon catch by 2050.

And in a study released Thursday in the journal Science, researchers found that if the planet continued on its current fossil fuel emissions trajectory, mass extinction events could ripple across the world’s oceans by 2300.

As sea creatures face their ecological limits, such mass die-offs would spiral into a “Great Dying” equivalent to the end-Permian extinction, a period 250 million years ago when over two-thirds of the planet’s marine species were snuffed out, found two scientists from Princeton University and the University of Washington in Seattle.

Reversing greenhouse gas emissions trends, however, would lower extinction risks by more than 70 per cent, “preserving marine biodiversity accumulated over the past [approximately] 50 million years of evolutionary history,” found researchers Justin Penn and Curtis Deutsch.

For Harley, those findings — as well as the fallout from tragic events like last year’s heat wave — offer anyone who listens or remembers a choice.

“I never root for climate catastrophes, but when they happen, I hope it serves as a wake-up call,” he said.