A SkyTrain extension to the University of British Columbia should include four or five stops and be largely built underground, the region’s mayors agreed at a meeting Friday.

However, many at the Mayors’ Council meeting — held to recommend a “base scope” of the UBC extension — alluded to concerns TransLink was putting the cart before the horse by not assessing costs of the plan and various alternatives.

“When can we answer the elephant in the room: the costs of this project?” asked Jen McCutcheon, director of the North Shore’s Electoral Area A.

The mayors agreed for TransLink staff overseeing the extension to return a cost analysis of the proposals, which form the basis of a business case should funding become available in the future.

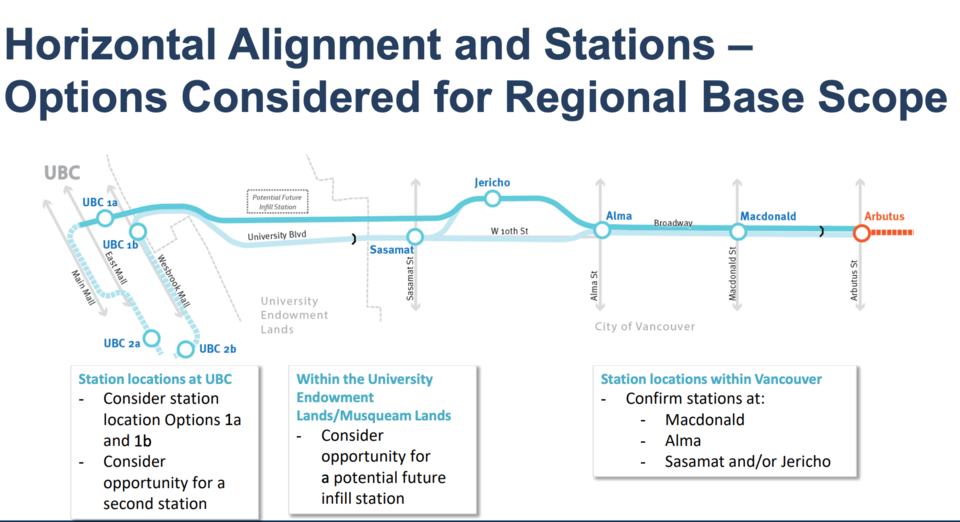

Until then it was agreed that the proposed line should include stops at Alma Street, MacDonald Street, Jericho neighbourhood and the UBC bus loop. A future fifth station will be designated nearby the university golf course inside the University Endowment Lands.

A second station at UBC was not recommended due to costs, which were not stated in a report to the council. (The Mayors' Council oversees TransLink’s planning.)

As well, an alternative station at Sasamat Street was rejected.

The only place an elevated line could be built is within the endowment lands, along University Boulevard; otherwise the line, dubbed "UBCx" will be underground.

In 2014, the Mayors' Council approved the 5.7-kilometre SkyTrain line now being built from Vancouver Community College in East Vancouver to Arbutus Street, to alleviate the Broadway corridor.

However, the mayors stopped short of UBC due to costs, and so the line’s endpoint means university visitors and residents will need to board a rapid bus line to get to the university.

In 2019, the council approved SkyTrain as the go-to technology for extending the line that could carry 130,000 people per day by 2050. Last month, Vancouver City Council endorsed the proposed line.

A 2019 study pinned the costs at between $3.3 billion and $3.8 billion.

Much of what the public may be on the hook for depends on a coalition of First Nations developing condominiums on the 90-acre Jericho Lands, in partnership with the Canada Lands Company, a federal government real estate manager.

A second factor is the Musqueam Indian Band’s desire to further develop its lands around the university’s golf course, where a proposed fifth stop will be “cut out.”

A third factor is the university’s yet-to-be-determined financial contribution to the line, which is partly predicated on land value lift from the line.

Richmond mayor Malcolm Brodie said this “third-party funding” is important to understanding how the line will work.

Many mayors from outside the Vancouver core expressed a desire to better understand transit funding models not just for the proposed line but for public transportation on the whole. This includes what senior governments are willing to chip in.

Pitt Meadows Mayor Bill Dingwall noted ridership is down since the pandemic as are regional revenue streams from gas taxes (which pay for roads) due to fewer people driving and more electric vehicle uptake. And, said Dingwall, more taxes are “unsustainable.”

“Everybody wants to see public transit advanced,” but “we need to look at how we’re funding transportation,” said City of North Vancouver Mayor Linda Buchanan.

Anmore Mayor John McEwan said the line needs to come in at the “lowest cost possible,” a sentiment echoed by Port Coquitlam Mayor Brad West and Delta Mayor George Harvie.

“I want to see the most cost-effective route,” said Burnaby Mayor Mike Hurley.