City council heard Wednesday that it will cost $9.9 billion to build the new Iona Island wastewater treatment plant on land near the airport but the share Vancouver taxpayers will pay is still unknown.

Jerry Dobrovolny, the chief administration officer for Metro Vancouver, said Vancouver taxpayers can expect to pay the bulk of municipalities’ costs because the city sends 95 per cent of its wastewater to the current plant.

Most of Richmond and a small area of Burnaby are also in what is called the Vancouver sewerage area, and will continue to send wastewater to the new plant when completed sometime after 2035.

“We're looking at different models in terms of what the rates would be, but Vancouver pays 95 per cent of the total cost,” Dobrovolny said in response to a question from Coun. Lenny Zhou about taxpayers’ share. “And the more provincial and federal funding we get, that's a direct savings to Vancouver city.”

But how much money Metro Vancouver will get from senior governments is still a work in progress, with Dobrovolny noting he and his staff were in Ottawa earlier this week to meet with Dominic LeBlanc, the Minister of Intergovernmental Affairs, Infrastructure and Communities.

“We know that the elephant in the room is the cost obviously — this is a huge project,” he said. “There's really good awareness of the project [in Ottawa] and really strong support for the project. I didn't come back with a big cheque. We were hoping for that.”

'Quite a thin budget'

The first phase of the project, which will run over five years, is estimated at $750 million. Metro Vancouver’s funding formula is that the cost will be split three ways between senior governments and Metro Vancouver.

So far, the provincial government has committed to $250 million and Metro Vancouver has submitted government grant applications via the salmon restoration fund and disaster mitigation and adaptation fund to help with its $250-million commitment.

Metro is also working with the Canada Infrastructure Bank to borrow money.

“The federal government told us [Tuesday] night that this year's budget was quite a thin budget, and they were concerned about inflation and trying to pull back,” Dobrovolny told council. “We're hopeful that either the fall economic update or next year's budget will include Iona phase one funding.”

The project is already five years behind government-mandated dates to meet regulatory requirements under the federal Fisheries Act and provincial Environment Management Act to have the plant upgraded to a secondary level of treatment by 2030.

Those requirements coupled with the aging current plant, which was built in 1963, have driven the need for a new plant and higher levels of treatment; the current plan only offers a primary level of sewage treatment.

'Greatest salmon rivers in the world'

Council heard the new plant will treat sewage to a tertiary level, which is a standard level of treatment in North America and across the world. The existing plant is one of the few, if not the only, primary treatment plant on the west coast of North America.

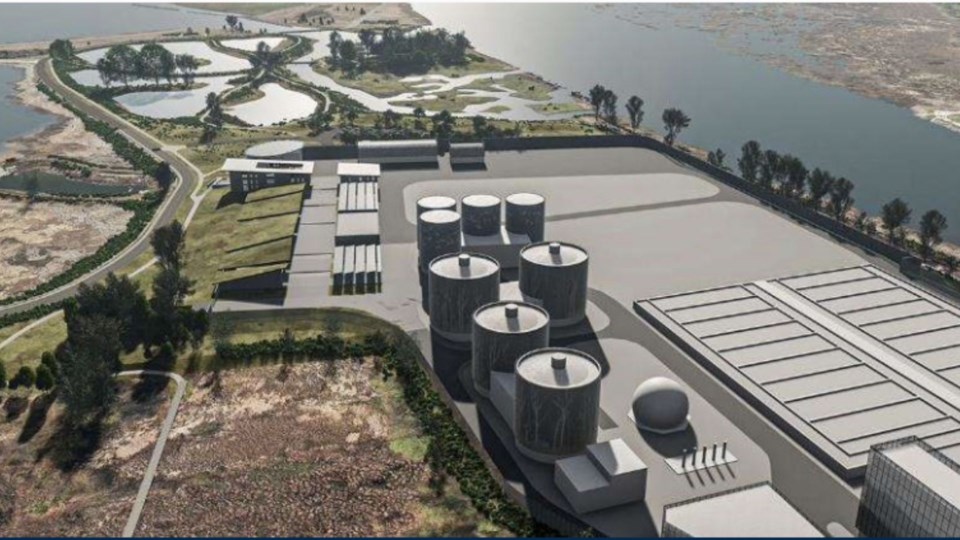

The advantages of that technology will reduce pollutants and better protect the Fraser River — “one of the greatest salmon rivers in the world” — and Salish Sea, but also be resilient to climate change and earthquakes and reduce greenhouse gases.

Ecological restoration projects dedicated to fish and bird habitats is also envisioned for the work, as is a barge facility across from Deering Island. Coun. Lisa Dominato said she has heard from some residents of Deering Island with concerns about the barge facility.

“We know that a sewage treatment plant, and also one of the largest construction sites in the region, is not an ideal neighbour, to put it lightly,” Dobrovolny said.

“So we know that we need to work together over time to develop plans. But we also know that tens of thousands of trucks [moving dirt] as an alternative is a much worse alternative, both in terms of congestion, safety and greenhouse gases.”

Cheryl Nelms, Metro’s general manager of project delivery, added that a consultant has been hired to conduct an “options analysis” of three potential sites for a barge facility. Nelms anticipated Deering Island residents would be consulted sometime this summer.

Musqueam Indian Band

When the existing plan was built in 1963, the region ran a large pipe through the Musqueam Indian Band’s reservation at the southwest end of Vancouver — without the band’s permission or involvement in the project.

The existing plant was built directly across the river from what is now the band’s cultural centre.

Dobrovolny emphasized the Musqueam are “full partners” in the new project. He noted the band has some “really ambitious business opportunities with us,” and are planning a very large district energy system using the heat from the sewer.

Dobrovolny said construction of the new plant will result in 100,000 person years of work.