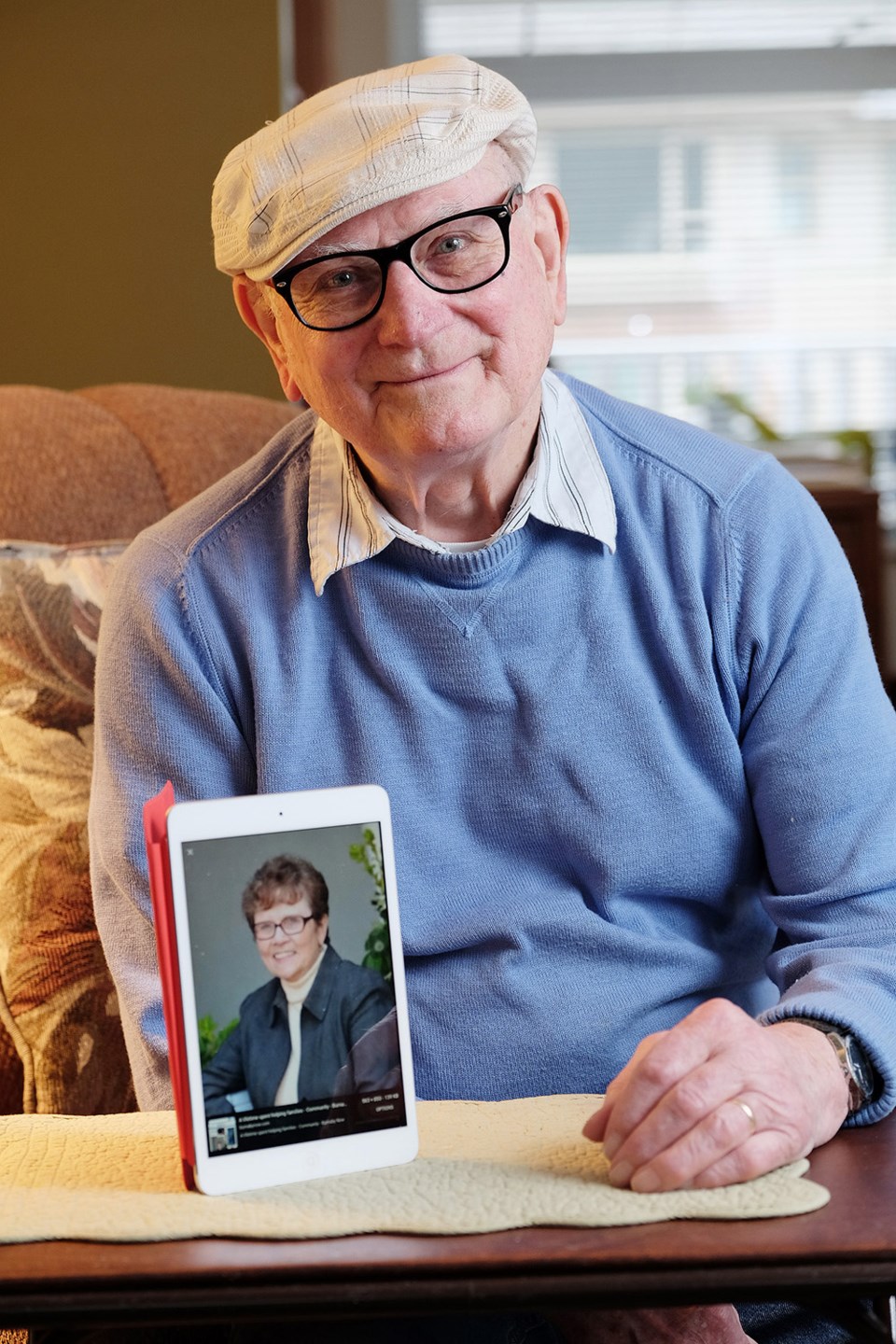

There were three things that kept Carol and Leo Matusicky calm in the face of death. A deep faith in God, a profound and abiding love for each other, and a sense of humour. It was that trinity, as Leo calls it, that kept them going, while Carol, a longtime Burnaby resident and advocate for children and families, lived out her final days at home.

How they met

It was the `60s, and Carol Storrow and Leo Matusicky were grad students stuck in a symbolic logic class together in the University of Notre Dame.

"It was all mathematical nonsense. They didn't talk in words; they talked in symbols and numbers," Leo recalls.

One day, after everyone had left the class, Leo noticed Carol crying by the window following a particularly vicious exam.

"Why the tears?" he asked.

Carol explained she had always earned As and Bs, but this time she received a D.

"I showed her my exam, and I had an F," Leo says, laughing. "I said, 'By the way, miss, what are you doing tonight?'"

Leo took her out for dinner, and that was that.

They married in 1975, moved to Burnaby and raised two kids. Carol went on to pursue a doctorate in family studies, which led to a lifelong career helping children and families at the policy level.

"We had a deep respect and admiration of each other. It was a beautiful relationship, and I can't express it other than we were deeply attuned," Leo recalls. "Mutual respect, a sense of humour, balance, humility and sense of judgment - it's very difficult to express, but we sensed it in each other almost immediately."

The diagnosis

In 2012, Carol, then in her 70s, began to have trouble holding things. She assumed it was arthritis, until she got her first diagnosis in November. It was amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, or ALS, an incurable, fatal disease that kills the brain's neurons till the patient can no longer move or breath.

"Being so close to Christmas, we decided to keep that to ourselves," Leo says.

In January, they informed the family.

"We decided to be strong together in confronting this malady so we could be strong for others," Leo says.

Progression

The Matusickys had help from the ALS Society, Fraser Health's palliative care team, the ALS team at Vancouver's GF Strong Rehabilitation Centre, and compassionate friends and family. Leo was at his wife's side, along with their two children, but the disease tightened its grip on Carol.

"(When) ALS reaches a certain stage, there's no stopping it. It's like a train without brakes going down the hill. She could hardly help herself - lost the use of her hands and arms, couldn't walk, she would lie hours and days on end. ... Slowly, slowly she just withered away," Leo says.

'I'm such a burden'

At times, Carol would say, "Oh honey, I'm such a burden," and Leo would snap at her, "You're not a burden, you're a pain in the ass!"

It was her debility that made her a burden - she had to accept that - and it was his duty and to care for her, Leo says.

"Don't you remember the vows were took some 40 years ago?" he said to her. "For better or for worse! Well, you're in bad shape, kid. Accept that fact and accept that I have a right and privilege to serve you."

And with that, she finally got the point, because she was a very independent woman, Leo explains.

The choice to die at home

In the last days, Carol knew she wanted to die at home. Leo helped get the paperwork in order. The doctor visited, and Carol signed a do-not-resuscitate order. They had all the necessities to make her comfortable at home.

By Dec. 5, Carol was nearing the end of life. Her breathing was shallow, and her pulse was terribly low, about 15 times per minute, and her eyes were rolling back in her head. The family was given a shot for this moment - morphine, enough to ease any pain and put her over the edge. Their son, Joey, offered to administer the dose, wanting to ease his mother's suffering.

"Dad, if you don't give it to her, I will.'" Leo recalls him saying. "I said, 'Joey, give that to me. It's my duty.' And I said to myself, my privilege."

The nurse offering guidance over the phone said Leo had to give her the shot even if it was the last thing he would give her.

"That was tough," he says.

"You can see we weren't there to kill her. We didn't want her to suffer anymore than she was already willing to suffer for us and for herself, so I said, 'Honey, this is it. Sometimes true love is letting go.'"

Leo administered the shot. There was enough time to call in relatives and a minister to read her last rites. Carol's breathing slowed and then stopped. Her grip on his hand loosened.

"I went to a bathroom, got a mirror and held it up to her to see if there was any moisture on that mirror, and I knew she was dead," he says.

Dying with dignity

Leo has been clipping and saving news articles on the recent Supreme Court of Canada decision allowing people suffering with an incurable, fatal illness to choose when to end their lives. But he makes a very strong distinction between assisted suicide and palliative care.

"The goal of euthanasia is to end life in order to forgo suffering. The goal of palliative care is to live well until you die, not to hasten or postpone death," he says.

It's the motive and the means that make the difference, Leo explains.

"There is a distinction. I know it's very fine, but there's a difference. One begs to get out of this life by ending it. The other accepts the fact that they are leaving this life, and they asked for compassion and to help us ease them out of life. They accept the same consequences."

If more people saw the possibilities of compassionate palliative care, Leo suspects there would be less interest in taking one's own life in the face of an incurable, fatal illness.

Advice for others

Carol's death was an incredibly emotional, intimate experience for Leo. He supported his wife's decision to die at home, even though some family members thought she should be in hospital. The ALS didn't affect Carol cognitively, and she was fully capable of making competent choices, Leo explains.

"I never made a decision for Carol. I listened to her, and I would turn to her and go, 'Honey, we're going into this together. What is your take on this? How do you feel?'"

He also has advice for caregivers who plan to be at their partner's side in those final moments.

"Make sure your decision coincides a with the psychological, emotional and physical needs of the one you care for. In other words, your feelings cannot override her choice and needs. That's what a caregiver is, and that calls for sacrifice on the part of the caregiver."

Leo also suggests making up a "trinity of care" with one's partner. For Leo and Carol, it was faith, love for each other and humour.

"There should be that mutual understanding that this is the way we're going and we chose it together.

I bend my will to her needs. That's the best advice I could give," he says.

"She was able to die in the peace of God," Leo adds. "We gave her the best, most loving care, and she died amidst the ones she loved, that she chose, and we honoured that."

There are some things no amount of planning or medical care can cure. Leo is now deeply grieving the loss of his wife, his lifetime partner.

"Tis better to have loved and lost than never to have loved at all," he says, quoting Alfred Lord

Tennyson. "I can say with an oxymoron, that I am happy I have loved and lost, because it at least shows I have loved."

Planning to die at home

Source: Fraser Health

Fraser Health runs an End of Life Care Program and provides hospice palliative care services to clients and their families in the end of life.

Fraser Health has an interdisciplinary hospice palliative care consultation team that works with Home Health nurses to relieve suffering and improve quality of life for people with a life-limiting illness. This includes exploring and supporting the wishes to stay home at the end of life, or in a home-like hospice residence such at St. Michael's Hospice Residence in Burnaby. People may also need additional care and support through tertiary hospice palliative care units, like the one at Burnaby Hospital.

Talk with your doctor and family, particularly if you have a life-limiting illness. These conversations aren't always easy, but it's important that they know and understand what your wishes are for advanced care.

Once you start these conversations, or if you don't have a doctor or anyone else to talk to, you can call Fraser Health's Home Health Service Line at 1-855-412-2121 to find out about the type of services you can access. Our staff can help guide you and your loved ones through the process, and explain what is needed to fulfill your end of life wishes.

For more information about hospice, palliative care, visit http://fraserhealth.ca/your_care/hospice_palliative_care.

For more information about advance care planning, visit http://www.fraserhealth.ca/your_care/advance-care-planning.