To know where we’re going, it’s always good to know where we’ve come from. In honour of this summer of celebration, as Canada marks the 150th anniversary since Confederation, we’re taking a wander back in time to see what life was like closer to home. While the Fathers of Confederation were gathering to consider forming the new country of Canada, life on the West Coast was still rough and tumble. Here, in what was not yet Burnaby, was a forest with a handful of settlers. Here, too, was an unfolding political drama as opposing forces eyed two different sites for the capital of the new colony of British Columbia. It was the forces of Col. Richard Clement Moody setting up the capital in New Westminster who shaped the beginnings of Burnaby. At Moody’s side was a private secretary who was “in it to win it” – a man who would give his name to a lake and, eventually, a city. The man was Robert Burnaby. For more, read below.

Burnaby would have looked a whole lot different had Col. Richard Clement Moody not made New Westminster the first capital of British Columbia.

“B.C. was its own colony during the gold rush in 1858. The biggest trajectory change in Burnaby’s history was Moody selecting the capital,” says Jim Wolf, a local historian and author of Royal City: A Photographic History of New Westminster.

Burnaby would incorporate on Sept. 22, 1892, but before then, it was nothing but a dense forest with around a dozen settlers.

Wolf, who’s now the senior long-range planner for the City of Burnaby, says a lot of pieces had to fall into place before Burnaby would become the city it is today.

Before Confederation

Prior to joining Confederation in 1866, British Columbia had been its own colony since 1858.

Gov. James Douglas had set his sights on Fort Langley to become B.C.’s capital.

“He was basically your first politician that had, let’s say, alternate intentions,” says Wolf. “The alternate intentions were that he and his friends and family all benefited through decision making. He said, ‘I’m going to create a little town site, I’m going to sell it off and guess who gets first pick? Me and all my friends.’”

But the colonial office in England had a different view of things. The Brits were worried B.C. would be annexed by the Americans since the gold rush in California had petered out, and a host of Americans were making their way up to British Columbia’s Cariboo for its gold, according to Wolf.

“(The Brits) were like, ‘We’re going to lose this place if we don’t take control,’” he says.

Building the foundation

In response, Britain brought in the Royal Engineers who were led by Moody. The colonel was appointed lieutenant-governor of the colony and the Royal Engineers were tasked with building roads, bridges and everything that goes with setting up a community.

“As he’s coming up the coast, he’s hearing rumours that Douglas had established the capital without consulting him. Moody says, ‘We’re not doing this; that’s the wrong thing to do,’” says Wolf.

Shortly after his arrival, Moody found New Westminster by travelling up a channel of the Fraser River.

“He immediately says, ‘This is going to be the capital city; this is going to be a great metropolis and New Westminster is easily defendable. It’s on the north side of the river; it’s at the confluence of where all the forks of the delta come together, a perfect site from a military perspective,” Wolf tells the NOW.

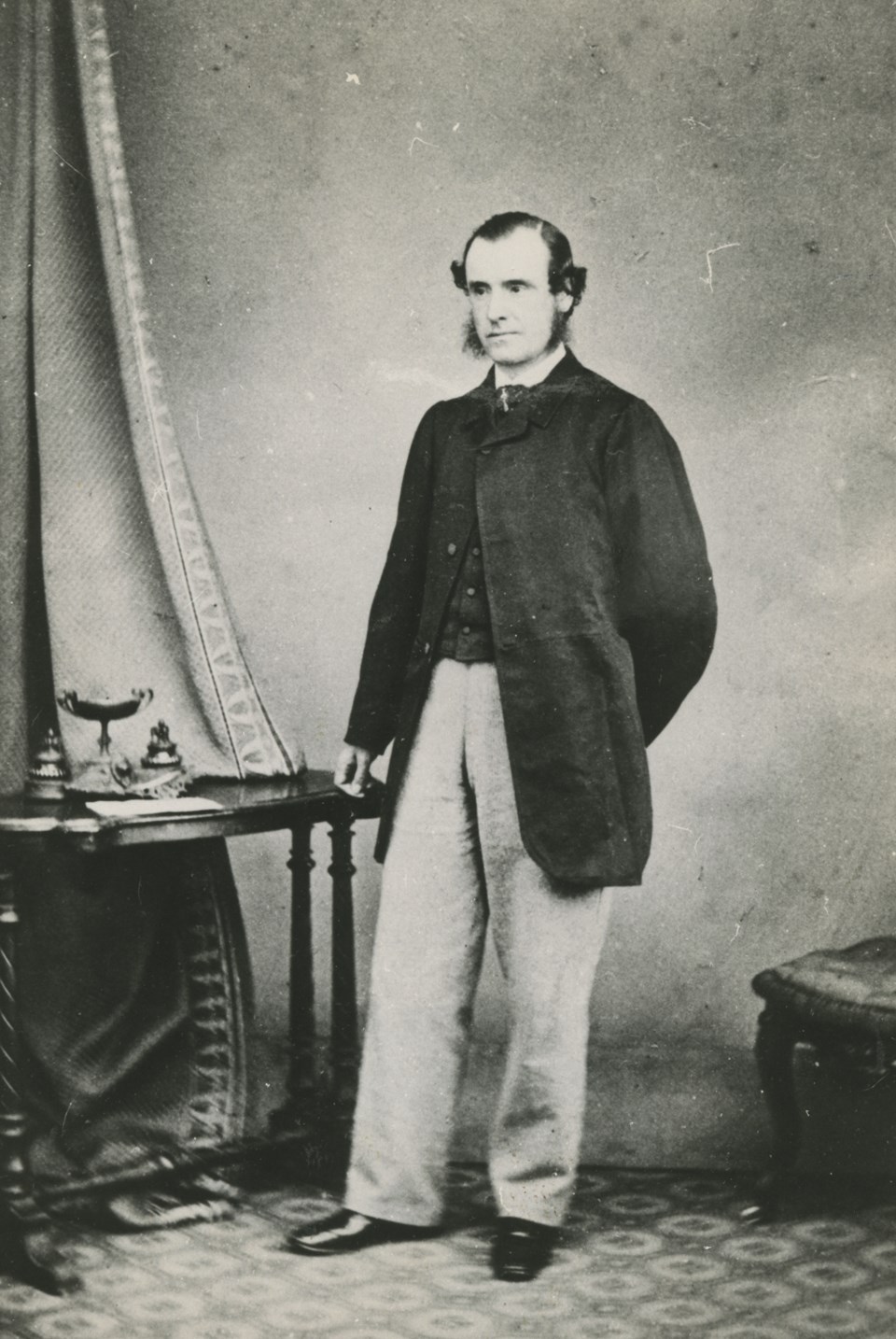

It was at that point Moody needed a private secretary, so he hired Robert Burnaby – someone who was “in it to win it,” says Wolf.

“He doesn’t take the position for money. He takes the position to see what he can get out of it.”

Learning from First Nations groups that a fresh water lake existed on the other side of New Westminster, Moody sent Burnaby to go find it. (New Westminster needed a source of water to serve the newly minted town.)

“Certainly, they find it with their (Indigenous) guides, and the lake gets named after Robert Burnaby,” explains Wolf.

The river, meanwhile, was named the “Brunette” after its brown colour, stemming from the peat-rich soil.

Moody quickly realized that once winter came, the freshwater river would freeze over.

“There’d be no way for the ships to come out, so he says, ‘I need a back door to the salt-free Burrard Inlet.’”

That’s when a military trail going north was built (today’s North Road).

“That created the grid for the City of Burnaby,” says the historian.

Following North Road was Douglas Road (today’s Canada Way), which went from Eighth Street and Columbia straight up into the woods and headed right for the Burnaby Lake valley.

Moody then built what is now Marine Drive in 1862, followed by a trail all the way to English Bay (today’s Kingsway).The colonel wanted a 360-degree view of the Lower Mainland, and out to English Bay, to protect New Westminster.

Moody found an area at the top of the ridge where a natural fire had burned the whole hillside. It’s there he set aside a military reserve for the defence of the city that is today’s Central Park.

Subdivided land

At the time, Burnaby was subdivided into some 200 160-acre chunks. Colonels like Moody were paid in land, but for anyone who wanted to settle in the area, they had to apply for what was known as a Crown grant. Settlers had to move onto the land and clear an acre in order to get the title. After that, they could move on.

Burnaby’s first settler was William Holmes from Ontario.

“It was a land grab like no other,” says Wolf. “They (England) wanted British subjects coming in, grabbing the land and settling there, and creating ownership. It was all part of a strategy in order to protect British Columbia from annexation by the United States.”

Co-existing with First Nations

But the settlers weren’t alone. Burnaby’s small population also consisted of the Kwantlen, Musqueam, Squamish and Tsleil-Waututh First Nations.

“In North Burnaby, you had the Tsleil-Waututh, and where Barnet Marine Park is today, that was called Thluck Thluck Way Tun, meaning the place you go to peel bark in the springtime,” says Wolf. “The women would go there to peel the cedar trees to get the cedar, to make the clothing, the blankets, and everything else they needed. There was this wonderful sense of First Nations people using all these lands in Burnaby, and that completely changed by the 1860s because of pioneer settlement.”

Wolf adds the Colony of B.C. never put in the infrastructure to help First Nations.

“The colony made up its own rules and did not protect the interests of local First Nations, including not creating treaties or reserves for them,” he says. “They just sold the land to the highest bidder, alienated First Nations land from those people. That legacy is probably one of the most enduring impacts that we see to this day.”

‘Everything falling apart’

In 1867, Burnaby had transportation networks leading out of New Westminster.

“You had the makings of a community already,” notes Wolf. “Those early years and the work of the Royal Engineers created the foundation of the city we know today.”

But when the gold rush ended in the late 1860s, “things were at their most dire for British Columbia.”

“It did not look good,” he says. “All of a sudden, very quickly, you have everything falling apart. All the miners and all the people that flooded into the province to do this, all of a sudden were looking around and there’s no gold. There’s no reason to be here. Everyone started to go back home.”

B.C. joined Confederation in 1871, a deal sealed by the promise of a national railway linking B.C. to the eastern provinces.

Wolf says had there been no gold rush and everything that followed, Canada’s and Burnaby’s history may have been different.

“I think there would have been more likelihood that this unorganized territory could have been taken over by American interests.”