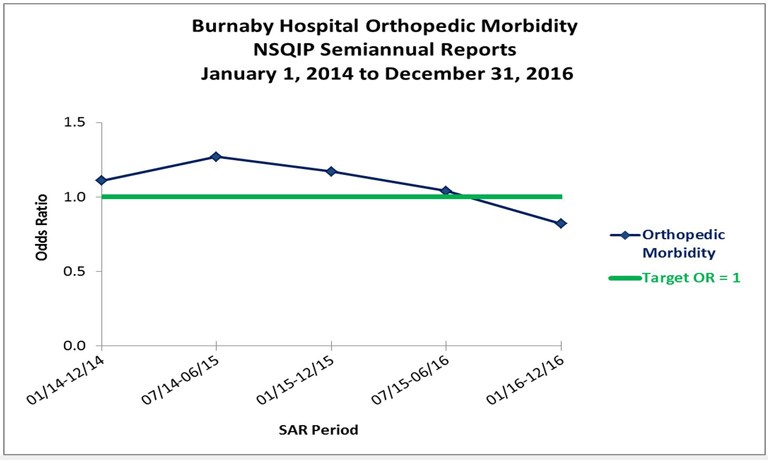

For orthopedic surgeon Dr. Tim Kostamo, the downward curve on a graph showing orthopedic surgery complications at Burnaby Hospital over the last few years is a thing of beauty.

“We’ve just got this beautiful kind of trend that just shows that, as our volume has gone up, our experience has gone up, that our complication rates are just coming lower and lower,” he told the NOW. “It’s beautiful to see that.”

The orthopedic data, which includes things like blood clots and infections, is just one set of indicators tracked through the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (NSQIP).

This year, Burnaby Hospital’s NSQIP numbers were so good it earned “meritorious” standing, putting it in the top 10 per cent of 680 Canadian and U.S. hospitals in the program.

For Kostamo, who is going into his 10th year at the facility, it’s validation the local hospital is no longer the “ugly little sister of Fraser Health.”

“Here’s these numbers saying that, hey, it’s not,” he said. “Burnaby right now is doing an awesome job in these things. I think that’s big news.”

Things weren’t looking so good for the hospital three years ago, when it was hammered in a provincial review of the Fraser Health Authority.

The report found Burnaby Hospital had been the worst in Canada for two years straight between 2010 and 2012 for “nursing-sensitive adverse events,” a category that includes hospital acquired urinary tract infections, pneumonia, pressure ulcers and in-hospital falls leading to fractures.

It also ranked in the worst three per cent of similar hospitals for fixing fractured hips within 48 hours and had “multiple outliers and needs-improvement areas” in its NSQIP data.

Politicians and doctors have blamed some of the hospital’s problems – including deadly outbreaks of the superbug C. difficile about six years ago – on the facility’s age.

Parts of it are more than 65 years old.

During the provincial election, Premier John Horgan promised to fix up the hospital and then replace it for an estimated $2.1 billion.

"We're going to make sure that the existing facility is up to a standard that the people of Burnaby can be comfortable with, but that hospital needs to be replaced, and we're going to build a new one," Horgan said in April.

Despite its age, however, Burnaby Hospital currently “totally punches over its weight,” according to Kostamo.

“Sure, we have an older facility,” he said, “but there’s nothing I as a surgeon can do about that. There’s nothing the staff can do about that, but we’re the highest volume of total joints in all of Fraser Health. We’re doing operations in our little community hospital that they’re not doing anywhere else in Fraser Health, like hip arthroscopy.”

NSQIP is one of the tools hospital staff have used to turn things around, according to Kostamo.

Burnaby was the third B.C. hospital to join the program – run by the American College of Surgeons – in 2009.

A NSQIP dedicated nurse, Darlene Jaeger, gathers and submits data on 238 different procedures for six broad categories: general surgery, orthopedic surgery, urology, plastics, otolaryngoscopy (ear, nose, and throat) and gynecology.

The hospital can access raw NSQIP data any time, but four times a year the program also sends reports showing how Burnaby’s numbers stack up compared to other hospitals.

“It’s easy to look at what you’re doing yourself and say, ‘Hey, I’m doing great.’ I think that’s just how we are,” Kostamo said. “To prove it, I think you’ve got to look at what the other hospitals are doing. I think the more you compare, the more powerful it is.”

Take hospital acquired urinary tract infections (UTIs).

About three years ago, Kostamo said, the NSQIP data showed Burnaby was consistently registering high UTI rates in relation to other hospitals.

After discussions about possible causes, the hospital changed its practice of automatically inserting catheters in certain patients (like those with hip fractures); implemented an education push reinforcing proper, sterile techniques for catheterization, and switched to a different kind of catheter.

Since implementing the changes, the hospital’s UTI rates have gone from “needs improvement” to “as expected” in all surgical areas, and to better than average for general, orthopedic and plastic surgeries.

Like many other improvements at the hospital in recent years, the process was sparked by solid data, according to Kostamo.

“If you don’t have the data, you can’t make decisions,” he said.