To Anelyse Weiler, crops rotting in the fields and alleged violations of migrant workers’ rights are just two sides of the same coin.

That relationship is essential to modern food production in Canada, explained the professor of sociology at the University of Victoria, and one that puts farmers and their foreign employees in difficult positions — but for different reasons.

“The food system has positioned producers, including farmers and farm workers, in a pinch point,” said Weiler.

“It’s one of the expected outcomes of a globalized, capitalist food system. That's one of the directions that we could predict from the system that we’ve adopted to feed ourselves, and it’s one that we take for granted.”

COVID-19 laid bare cracks in that system. Cracks that run deeper than disrupted supply chains and empty shelves. Cracks that tie together sky-high farm debt, land speculation, and Canada’s reliance on migrant agricultural workers.

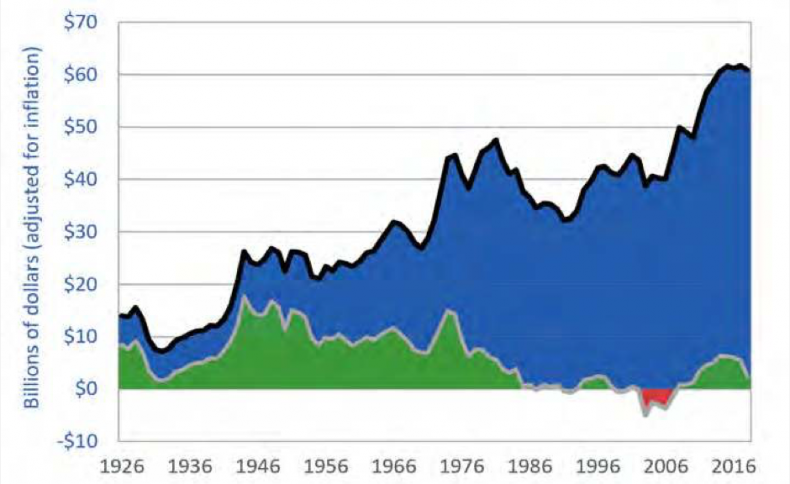

That’s because the prices farmers receive for their products often don’t cover their costs of production, a situation that’s largely been caused by consolidation at both ends of their production cycle.

Most mid- to large-scale farms sell to a few major grocery chains and food processors, the result of decades of consolidation in the industry in both Canada and the United States. This, in turn, allows those companies to set their preferred buying price — and these are often lower than the farmers’ costs of production.

Meanwhile, the cost to grow food has risen exponentially in the past 30 years.

“Over the last three decades, the agribusiness corporations that supply fertilizers, chemicals, machinery, fuels, technologies, services, credit, and other materials and services captured 95 per cent of all farm revenue,” noted a 2019 report by the National Farmers Union.

Farmland has also seen its value skyrocket since the Second World War, making it increasingly difficult for farmers to compete against other, more lucrative uses — golf courses or shopping malls, for instance.

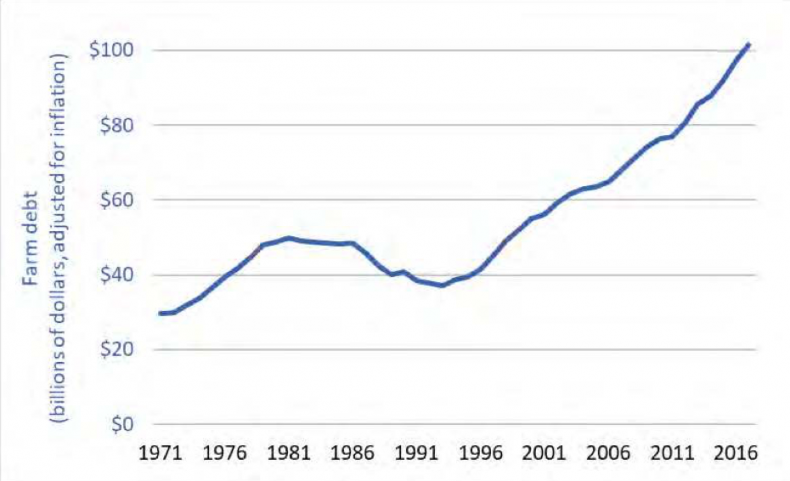

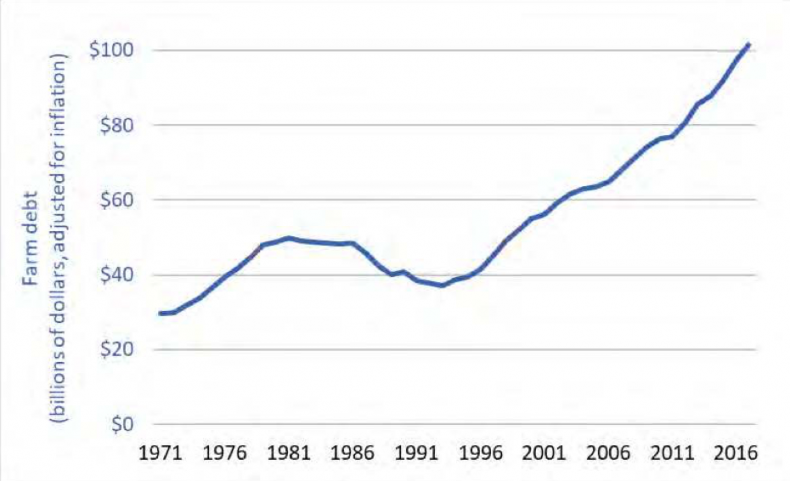

Combined, these factors have pushed Canadian farm debt to skyrocket, reaching $106 billion in 2019.

“Farmers have made the case that labour is one of the few variable costs they can control when they’re facing a price squeeze,” Weiler said.

That’s where migrant workers come in.

In the 1970s, Canada started developing a suite of temporary work permits designed to help Canadian employers fill specific labour needs with foreign workers — without giving them a means to emigrate permanently.

Two of these permits — the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program and the Temporary Foreign Worker Program’s agricultural stream — were designed specifically to supply Canadian farmers with workers.

Since they were established, these programs have become essential for Canadian farmers, Weiler explained.

In 2019, 58,800 people came to Canada through these two programs. About 10,950 went to B.C., most of them Mexicans arriving through the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program.That number decreased by about 17 per cent nationwide this year because of the COVID-19 pandemic.In B.C. this year, there were 39 per cent fewer workers in the province as of August, compared to the same period in 2019.

“Many migrant workers have extensive experience and training from repeated years of coming back to work in Canada,” Weiler said. “But their experience and expertise isn’t materially rewarded in the same way that we would see in other kinds of industries.”

Most of the Mexican workers hired through the Seasonal Agricultural Worker Program are farmers or have a farming background, Hugo Velázquez, an official at the Mexican Consulate who helps co-ordinate the program, said.

The program allows B.C. farmers to request specific workers by name — about 80 per cent of the Mexican workers in B.C. get their visa this way, he said — and many go back to the same farm year after year. Workers’ visas are tied to their employer, meaning they can’t change farms once they get to Canada.

Despite this continuity, they’re still usually paid about minimum wage to spend hours performing back-breaking and often dangerous work on farms.

It’s a job that only makes sense compared to the migrant workers’ possible earnings farming back home, explained Velázquez. If they were farming in Mexico, they’d be making roughly 200 Mexican pesos a day (about $12) compared to roughly $115 in B.C.

That means they’re willing to work for less than Canadians with similar levels of experience, a fact evidenced by Canadian farmers’ consistent failure to find reliable local employees.

It’s a discrepancy Amy Cohen, a professor of anthropology at Okanagan College whose research focuses on the experiences of migrant workers in B.C., said exposes deep flaws in the program.

“The power imbalance is so intense that workers are really incentivized to do anything that can please their employer or not anger them in any way,” she said.

Cohen said workers will hide injuries, won't complain about bad working or living conditions, and avoid criticism of their employers to Canadian or Mexican authorities to ensure their contract will be renewed yearly.

“We can’t speak out. It’s like shackles around our feet. We cannot say nothing, because we want to come back.” Migrant farmworkers across Canada discuss how some employers have prevented them from leaving the premises, even to purchase groceries. https://t.co/OkHL5ifKQs #cdnimm

— Anelyse M. Weiler (@anelysemw) August 4, 2020

The issue is particularly acute for women.

“Women are under a lot more pressure to maintain their positions because there are fewer options for them to obtain work on another farm, so they are incentivized in that way to put up with a lot more,” Cohen said.

“Also, for the female workers, they are mostly single mothers — whereas men are married — and these women are primary breadwinners without the support of a spouse.”

It’s a situation she said could be significantly improved if migrant workers were given permanent residency upon arrival — or at least an open work permit that would allow them to move between different employers.

It’s an issue Cohen has been lobbying the federal government on alongside several migrant workers’ rights organizations across the country.

Velázquez said that doesn’t align with his experience visiting farms and talking to workers. Most are relatively content with their situation, and the consulate tries to respond diligently to complaints of abuse. Many workers also don’t want to stay in Canada, he said.

“Farmers are very attached to their land, and many of them are like, ‘This is nice, but I just want to go home to my family.’”

Still, whatever its value for Canadian farmers and the temporary migrants working for them, the program is symptomatic of deeper issues in B.C.’s food system, Weiler said.

It’s critical to rethink the idea that if Canadian can’t hire cheap foreign labour, the entire system will collapse, she said. If farms can’t break even by paying their workers a Canadian living wage, it points to a fundamental devaluation of food — and the labour and resources needed to produce it.

“I think it’s something we really need to look at as a society and to think about what we value. I think there’s appetite for change — and there’s a lot to consider.”