Every time you see a group of crows mobbing a raven, seven million years of evolution are in play.

At about the same times that chimpanzees and humans began their separate genetic path, crows and ravens set out on their journey to become distinct species. Even though a raven might look like a beefed up version of a crow, and they share an equally keen intelligence, their fork in the evolutionary road means they are very different from one another.

Whenever UBC postdoctoral fellow Benjamin Freeman saw crows on campus ganging up on a raven — and winning the altercation — he was intrigued.

Shouldn’t the raven win because it was bigger? Isn’t the raven's size supposed to give it an evolutionary advantage?

Freeman wanted to know if his observations were just anecdotal or if there was empirical proof of this behaviour in nature. He turned to the data submitted to Cornell University’s eBird program. (Freeman completed his PhD at Cornell’s department of ecology and evolutionary biology in 2015.)

After filtering through all the volunteer reports about bird behaviour, he found about 2,000 posts pertinent to his study.

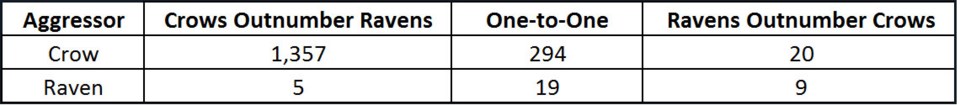

The data showed that what he saw happening at UBC was being echoed across North America. In angry crow and raven encounters, the crows were nearly always the aggressor — but only if there was strength in numbers.

In 1,357 cases when crows attacked ravens, crows outnumbered ravens; in only five similar situations was the raven the aggressor. That means that in 97 per cent of the time, it was crows chasing ravens.

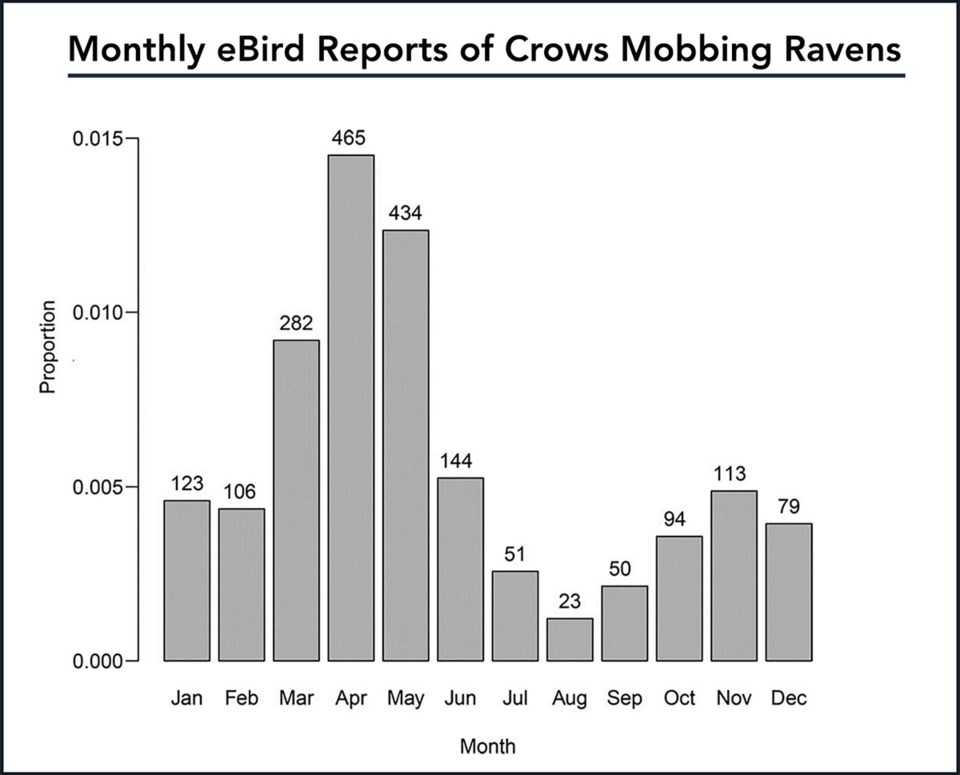

Freeman also charted when this mobbing behaviour occurred. Not surprisingly, most of it was in the spring and early summer — nesting and fledgling seasons. Ravens will eat crow eggs and baby crows so there’s an evolutionary imperative for the crows to fight back. Since crows have long memories and tend to take things personally — as anyone who has been dive-bombed by a crow can attest — their anti-raven behaviour knows no seasonal bounds. They chase ravens year ’round.

“Crows just don’t like ravens,” Freeman says.

And here’s where evolution has favoured crows. Ravens are solitary and usually frequent wilder habitats, which is why they tend to be outnumbered in urban environments. Crows are social creatures who do well in urban cities where they’ve learned to adapt to the plentiful food sources.

Attack one crow and you attack the tribe.

“If you gave crows and ravens equal motivation and put them in a boxing ring, the raven would win hands down,” Freeman told the Courier. In cases of low-grade harassment, the raven can easily hold its own.

But crows’ social behaviour allows them to punch above their weight. They put out the caw-caw to action and gang up on the raven. (You can tell a crow by its caw-caw vocalization; ravens croak.)

“The social behaviour of crows is really important,” says Freeman, who published his results in The Auk: Ornithogical Advances, co-authored with Eliot Miller, a postdoctoral researcher at Cornell lab. “It really helps them.”