The lanes went out quietly; the pandemic made sure of that.

If you asked Keith Stevenson why he loves five-pin bowling, he wouldn’t wax poetic about the thunderous rumble of the urethane ball on laminated hardwood nor its satisfying clash with the pins at the end of the lane. Instead, he’d tell you of the cheer that follows a strike or a tough spare. And that’s what he’s missed most.

“It goes back to people. You can’t be in this business and not get emotional not seeing these people,” Stevenson says. “Some of these leagues, I’ve been with them since Lougheed Lanes to Hastings to Old Orchard. I’ve seen their families grow. I’ve seen their deaths. It’s family.”

There was no chance for a last hurrah to celebrate the life of the Old Orchard Five-Pin Bowling Centre, Burnaby five-pin’s last gasp. No triumphant crash of balls and pins at the end of these lanes. No second chance to claim the spare. No closing frame. No final game. Only a few solemn balls thrown between Stevenson and his son – “My son grew up in a bowling centre,” he says – a day or two before, with “mixed emotions,” he surrendered the keys to the property owners.

Like innumerable other businesses throughout Canada, the Old Orchard lanes were snuffed out quietly by the coronavirus pandemic this spring – and with them, the five-pin game that bound a community left Burnaby.

✕

A linchpin for communities

Stevenson, who had run the Old Orchard lanes since 2014, says there’s something particularly special about five-pin that can’t be captured in the 10-pin game – namely, its accessibility.

While 10-pin bowling balls can weigh up to 16 pounds, they’re only about three-and-a-half pounds in five-pin. That allows much of the bowling community – whose members reach well into their 90s – to keep active without too much strain.

In fact, that’s the whole reason the uniquely Canadian sport was invented. In 1909, Thomas F. Ryan shaved a quarter of the size off 10-pin bowling pins at his Toronto venue after hearing from patrons that the 10-pin variety was too difficult for children and seniors.

In the century since the sport’s inception, seniors have found a social boon in five-pin leagues, the gravity around which friendships revolve amid a seniors’ loneliness epidemic. Those social connections can be vital for some senior bowlers who struggle to get out much beyond their weekly bowling day.

“And I think a lot of people would look forward to that day and meet people and maybe go for lunch or whatever,” says Joan Keller, who ran the Tuesday morning breakfast club league at Old Orchard. “You make friendships. I mean, I've got friends now that that's … how I met them is through bowling, originally.”

Phyllis Fox’s friends, who bowl together but not in a league, started out in the Lucky Strike Bowling Lanes in New Westminster. When that closed, they were forced to look at their options. The group ultimately landed at Old Orchard, but with this latest closure, the options for new venues are few and far between.

“I miss it very badly,” Fox says. “I’m so sorry that the virus hit because … I think that’s a big reason Old Orchard lanes closed, and I’m very mad about that.”

She considers her group lucky – being in smaller numbers, they’ll likely have a fairly easy time finding a new hangout. But with 15 leagues all scrambling to find a new space, some may have to disband altogether or fold into another league.

Among them are the church leagues that play in the evenings, the Special Olympics league and, the mainstay of the business, the daytime seniors leagues, such as the Tuesday morning breakfast league.

Keller says she hasn’t begun calling around to find new alleys to host her league of 30-odd bowlers, but she doesn’t sound particularly hopeful. There’s a bowling alley in Port Coquitlam, but it’s already a drive to Burnaby for the members who come from Vancouver. Meanwhile, Grandview Lanes on Commercial Drive doesn’t have adequate parking for a league.

“As of now? Yeah, it’s the end,” Keller says of the league. “It depends on what comes up.”

✕✕

Reclaiming stolen communities

In the 1950s, several bowling leagues hosted Vancouver’s Japanese-Canadian community, which continued to face discrimination and racism in the aftermath of the Second World War.

After the Japanese bombing of Pearl Harbour, the Canadian government stripped Japanese Canadians of their homes and placed them in internment camps. Even as the camps were dismantled in 1949, the discrimination didn’t end for Japanese Canadians – sometimes referred to as “Nikkei” or “Nisei” – as they returned from exile.

“For the young Nikkei returning to the coast, bowling on a Nisei league gave them a safe haven from the racial prejudices some were experiencing in the larger society,” writes Burnaby resident Masako Fukawa in a 2015 Discover Nikkei article on Japanese-Canadian bowling leagues in B.C.

Today, a few Japanese leagues continue, including the Fuji league, which got its start at Grandview Lanes but later moved to the Old Orchard lanes.

As a young girl, Fuji League treasurer Jean Wakahara returned to Japan with her family in 1946, after her time in the internment camps. But because she could hardly speak Japanese, she had trouble fitting in, and she was teased by her fellow classmates.

It was when she returned to Canada in 1958 that she felt she found a home, even though, by that point, she had to relearn English. She found a job and began bowling with the Yaba league, connected to the local Japanese Buddhist community. When that league folded, she continued to play the sport with the Fuji league, as well as a seniors’ league.

“I did have a rough time, a very rough life,” says Wakahara of her struggles as an English-speaking girl in Japan and her return to Canada speaking only Japanese. “But it really doesn’t bother me that much. I’m doing OK now, happy that I’m healthy, yet.”

She attributes much of that to having the Japanese bowling community – when asked if the bowling leagues helped to heal the Japanese-Canadian community, she’s quick to respond with an enthusiastic “oh, yes, very much.”

But now that the Old Orchard lanes have closed, the future of the Fuji league, which takes most of its membership from Burnaby, is also uncertain. Wakahara, now going on 85 years old, says she has no intention of returning to Grandview Lanes.

“If possible, I’d like to continue on. Just crossing my fingers,” she says.

The alternative is the league folds, potentially limiting opportunities to see some of the friends she’s made over the years.

“We got to know each other. I really miss them right now.”

✕✕✕

A kingpin bows out

“I’ve been enjoying my retirement,” Stevenson says, “but I wasn’t ready to retire, yet.”

The community that Stevenson has come to love will surely miss his absence at the helm of the local bowling centre as much as the Old Orchard lanes themselves.

“We had a very good relationship. Not only Fuji league; you could ask anyone that bowled at Old Orchard,” says Wakahara, noting Stevenson got to know patrons on a first-name basis. “You could ask anyone there how good they were, … and I’m sure they are very sad that they closed.”

By his own description, Stevenson stumbled into the business of running bowling alleys. He says he “fell into” a management position at the Lougheed Lanes, which centred his life even more on the game he had developed a passion for. After that, he came to own Hastings Bowl in the Burnaby Heights neighbourhood for 22 years, as well as Middlegate Lanes in Burnaby and another bowling alley in Vancouver.

Bowling was a way for him to find new friends when he moved to the region in 1976, and it became an escape from life and work. And then it became work. But while he’s been busy running the show at these bowling alleys, Stevenson says only a couple dozen days out of the last four decades truly felt like work.

“The passion became the people, the social aspect,” he says, “so many wonderful people that I retained friendships (with) for 30-odd years.”

When he came to Old Orchard lanes, Stevenson was happy to return from semi-retirement. But at 68, this time truly marks the end for him. If a new five-pin alley opens up, it won’t be Stevenson leading the charge – though he admits he’s happy to offer some guidance.

Now, at the closing of a 38-year career, it feels like the rug has been pulled out from under him.

“I was dealing with four or five hundred people a week,” he says, “and now it’s nothing.”

✕✕✕✕

Decades of decline

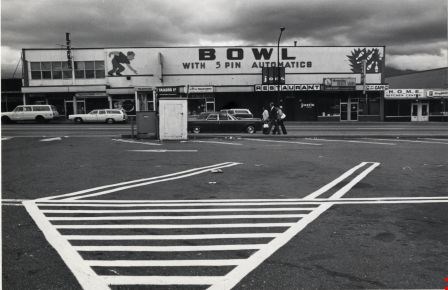

If five-pin is a sunset sport, as the NOW described it in 2014, then Burnaby five-pin has been in twilight for some time, Old Orchard’s lanes the final traces of light before slipping into darkness this spring.

Decades ago, when Stevenson got into the business, there were 13 bowling centres offering five-pin just in Vancouver. Now, there are about half of that in the entire Lower Mainland, and in Burnaby, Old Orchard was the last pin standing.

The game has been plagued with declining participation since the early 2000s, according to Stevenson. In 2014, he told the NOW that league participation had dropped precipitously, from over 1,600 in the 1990s to 440.

While Grandview Lanes attracts non-league bowlers, in part, through liquor sales, Stevenson says he lost potential customers due to that omission. But he doesn’t appear fazed by that – “We serve families, not alcohol,” he says.

What gets him is the challenge of getting youths involved, from children to young adults. That presents the greatest struggle for five-pin bowling, despite the fact the five-pin game was invented specifically to accommodate children, as well as seniors.

For the emaciated industry, the unexpected can be a particularly existential threat.

Hastings Bowl was a “special” bowling centre, apparently immune to five-pin’s decline, Stevenson says. Still, when disaster struck nearly a decade-and-a-half ago, the lanes couldn’t pull through.

In November 2006, the remnants of Typhoon Cimaron waded into Vancouver, where it mustered enough Pacific moisture to dump around 100 millimetres of rain. The weight of the water caused the roof to collapse on the two-storey building that housed Hastings Bowl. The building later caught fire, putting Stevenson out of the business.

But it was the fall of Hastings Bowl that kept Old Orchard going as long as it did, Stevenson says, with many bowlers seeking a new venue.

✕✕✕✕✕

Old Orchard’s last gasp

Old Orchard brought Stevenson out of semi-retirement and back into the bowling business in 2014, when the lanes were ailing financially and on the brink of closing. With Stevenson taking over the business, a new rent agreement was struck with the property owners, holding the lanes on life support.

The new rent agreement – at a lower price than the going rate, according to Stevenson – allowed the lanes to continue month to month.

In the meantime, Stevenson worked to make the place more attractive, including investing in electronic scoring, an upgrade from the manual pen-and-paper score cards. But the property owners continued their search for a new tenant that could pay the full rent to fill the space permanently.

It wasn’t the rental agreement, however, that ultimately did the bowling alley in. Instead, the Old Orchard lanes buckled under the weight of the pandemic.

With the last pin struck down in Burnaby, Stevenson is worried about the future of the sport that meant so much to him and his patrons. A handful of bowling centres have reopened since the onset of the pandemic, but it’s hard for him to see how they can last with physical distancing in place.

For many people, in mid-March, everything about the pandemic was so novel and uncertain, the scale and longevity of this “new normal” still out of focus. The last league Stevenson remembers bowling was the Fuji league, which voted overwhelmingly at the time to continue bowling, despite the pandemic.

But shortly afterward, on March 16, Stevenson wrote on the Old Orchard alley’s Facebook page, saying the lanes were closed “for the next couple of weeks because of the virus.” He would notify patrons when they reopen.

And there it hangs. No announcement comes of reopening – nor of permanent closure. It simply ends on a cautionary note: “Be careful out there.”