Correction: An earlier version of this story said the proposal in question was dismissed by the planning committee. In fact, according to the minutes of the meeting, the proponents were told the city doesn't support spot rezoning and referred the matter to staff.

A B.C. union’s proposal for its new Lower Mainland headquarters with an “affordable” housing component in Burnaby has exposed a sizable rift in a traditionally labour-oriented city council.

The B.C. Government and Services Employees’ Union submitted an application late last year to develop five lots on Palm Avenue into its new Lower Mainland area office, along with “affordable” daycare and rental housing.

That housing is expected to include around 300 units in total, with at least half being at “affordable” rates, defined in this case as being affordable to members of its union. The level of affordability and the number of child-care spaces planned are yet to be determined.

Two independent councillors voted against the city considering the proposal, with one suggesting it offered a sweetheart deal to the union and the other calling the proposal’s appearance before council “fishy.”

Despite the objections from independent councillors Colleen Jordan and Dan Johnston, council voted in early December to direct staff to work with the BCGEU on fleshing out the proposal to bring it forward as a zoning amendment at a later date. That vote split along familiar lines, with the majority coalition – made up of the independent Mayor Mike Hurley, the Burnaby Citizens’ Association’s three remaining councillors and the Burnaby Greens’ sole councillor – voting in favour of the proposal without comment.

After that vote, both Johnston and Jordan voiced exasperation.

“Pretty sad. Pretty sad. Pretty sad, indeed,” Johnston could be heard saying as the next agenda item was introduced by Hurley, who in turn had Johnston’s mic muted.

Hurley and the BCGEU, in turn, have shot back at the two, saying they voted in favour of policies that left many Metrotown residents demovicted with little recourse. The union’s treasurer, Paul Finch, says he’s “appalled” by Jordan and Johnston’s critique of the proposal.

Sticking to the plan

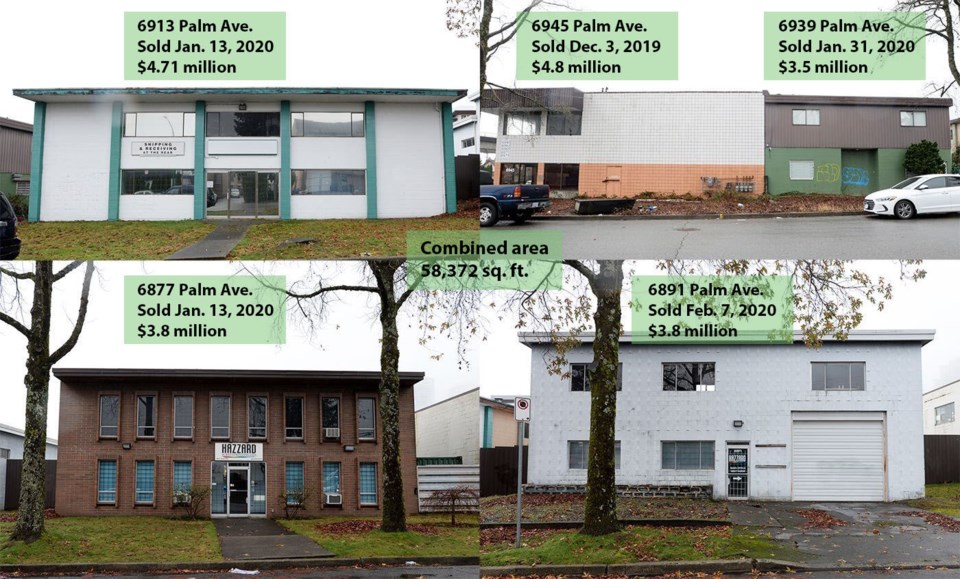

These five lots, spanning an area of nearly 58,400 square feet, sold to the B.C. Government and Services Employees' Union between December 2019 and February 2020 for a combined $20.6 million. By Jennifer Gauthier/Burnaby Now

These five lots, spanning an area of nearly 58,400 square feet, sold to the B.C. Government and Services Employees' Union between December 2019 and February 2020 for a combined $20.6 million. By Jennifer Gauthier/Burnaby Now

The issue is rooted in which developments are considered for rezonings and where. Based on the location of the BCGEU’s proposal, Jordan says the reduced property values would save the union millions of dollars, which she says is an unfair advantage coming from a union-friendly council.

The lots are currently in a light industrial area occupied by small warehouse-type buildings, five of which the BCGEU wants to replace with its headquarters. The problem, according to Jordan, is that the application submitted by the union doesn’t conform with the community plan.

The five lots, between 6877 and 6945 Palm Ave., are about a block east of Royal Oak Avenue and a block south of Imperial Street, which form the borders between the Metrotown downtown plan and the Royal Oak community plan. While the Metrotown plan has been updated in the last few years, the Royal Oak plan, which contains the Palm Avenue properties, is decades old and doesn’t have the same ambitious density aspirations.

The Royal Oak plan currently calls for RM3, or medium-density residential, at that location, while the requested zoning is for a combination of RM5r, or high-density residential, RM3 and a commercial component. In total, the requested zoning amendment would nearly double the density called for by the community plan.

So why is this a problem?

The BCGEU's Palm Avenue properties it just a block south and a block east of the border of the Metrotown downtown plan. If it were within the plan's borders, it would already be zoned for high-density residential. By Google Maps/Screengrab

The BCGEU's Palm Avenue properties it just a block south and a block east of the border of the Metrotown downtown plan. If it were within the plan's borders, it would already be zoned for high-density residential. By Google Maps/Screengrab

Jordan points to the City of Burnaby’s long-standing policy of not doing spot rezonings, in which city council decides zoning on a lot-by-lot basis. Instead, the city leans heavily on its community plans and rarely deviates from them.

Neighbouring Vancouver practises spot zonings without an official community plan in place to guide decisions on the issues. That has left the city largely immobilized by rezoning applications that face significant community backlash – and council can’t easily deflect that backlash without an OCP that allows for such developments.

What’s more, Jordan points to a 2014 Tyee piece by UBC urban planner Patrick Condon, who says spot zoning in Vancouver is “corrupting its soul,” with the city leaning on massive projects and the correspondingly massive fees that come with them to fund community amenities.

In an email, Condon said he “vociferously” opposes spot zoning, which he called a “bad idea in general,” but he said he does not know enough about planning in Burnaby to comment on this particular project.

However, in a later email, after the initial publication of this article, Condon clarified his objections to spot zoning are around the inflation it incurs on land values, which typically benefits land speculators and with little benefit to residents.

"A neighbourhood-wide planning process is always to be preferred, assuming there are development controls in place to stream land value gains into permanently affordable housing. This time, and in the absence of an updated (Royal Oak) plan, BCGEU acted on its own. Rather than the city being the agent for housing equity, it is the BCGEU streaming potential land value into affordable housing for member families," Condon says.

"If I had been on council, I would have voted in favour of the project, which, against the background of discretionary authority the city affords council for projects meeting affordability targets, would have allowed me to sleep soundly post-vote."

With an official community plan – and the various, more granular plans that envision the futures of various neighbourhoods – Burnaby urban planning comes with certainty for developers and neighbours, and it offers a sturdy foundation on which council can base its zoning decisions.

“The big deal about that is (the proposal) could be 20 blocks east of the Metrotown plan, it could be anywhere,” Jordan says in a January interview.

In other words, Jordan warns a spot rezoning could open up floodgates of speculation on properties and cause an influx of applications to rezone properties throughout the city for uses not permitted in the community plan.

That’s because the OCP – because of the certainty it provides – can mean a massive price differential for properties from one plan to the next, depending on how the neighbourhood is planned for zoning.

The five lots proposed for this development, at a combined 58,000 square feet, sold for between $2.1 million and $4.7 million apiece, according to the BC Assessment website, totalling $20.6 million.

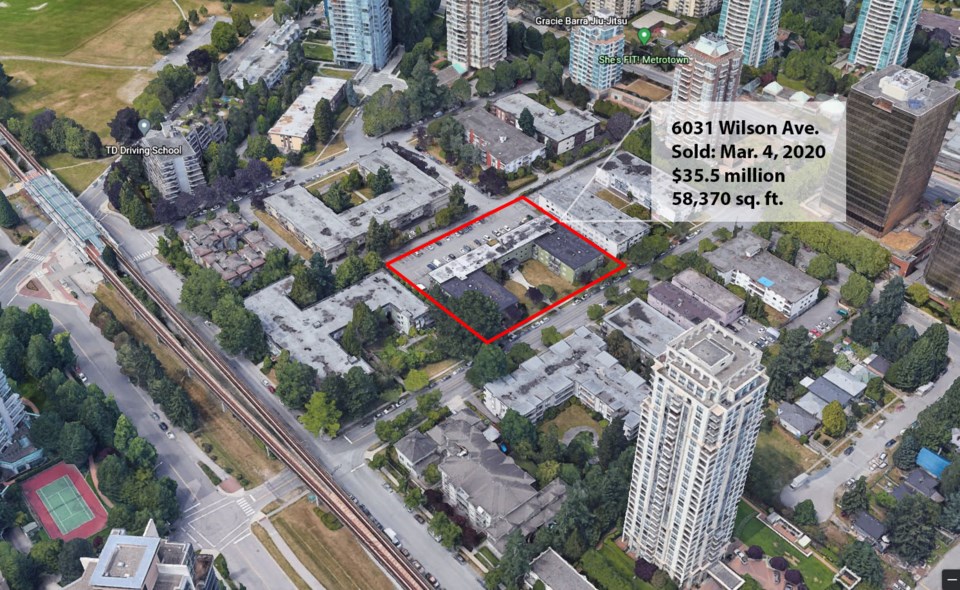

Jordan points to a similar-sized piece of land at 6031 Wilson Ave., which sits a short ways northwest of the Palm Avenue properties and which sold for $35.5 million in March 2020.

The substantially larger price tag is in part due to the property being already zoned for RM5r – the same zoning sought by the BCGEU, albeit without the commercial aspect.

Is this a problem?

This 58,400-square-foot Wilson Avenue property in the Metrotown downtown plan, already zoned for high-density residential, sold for $35.5 million in March last year. By Google Earth/Screengrab

This 58,400-square-foot Wilson Avenue property in the Metrotown downtown plan, already zoned for high-density residential, sold for $35.5 million in March last year. By Google Earth/Screengrab

Hurley disagrees on whether the Palm Avenue rezoning would, in fact, be a spot zoning, besides the commercial component of the proposal. While the proposal calls for doubling the allowable density, he notes the city’s rental zoning policy affords developers more density. However, it’s worth noting the proposal is not calling for RM3r zoning, the rental-oriented zoning that corresponds to the OCP’s designation for the area, but for RM5r, a higher-density rental zone.

And Hurley and Finch both pointed to the final report from the task force on housing affordability, which they said offered the city more latitude to consider proposals like these.

The task force’s second recommendation called on the city to “revitalize” its urban village plans, including through zoning and community plan changes, as well as calling for a review of the OCP “to identify more areas, such as arterial and transit corridors, where multi-family housing can be accommodated in a similar mixed-use, affordable, transit-friendly context.”

Finch says the BCGEU chose this location because of its proximity to major transit corridors around Royal Oak Avenue.

“I think council passed (the task force’s report) knowing what it meant, and that’s why our project is being considered – it’s completely in line with the goals of this community housing report,” Finch says.

“I’m actually appalled that (Jordan) would make that critique.”

‘Smells a little fishy’

A rezoning application by the B.C. Government and Services Employees' Union would change this block into a high-density residential and office space. The community plan only calls for medium-density residential. By Jennifer Gauthier/Burnaby Now

A rezoning application by the B.C. Government and Services Employees' Union would change this block into a high-density residential and office space. The community plan only calls for medium-density residential. By Jennifer Gauthier/Burnaby Now

In the years since the 2018 local election that saw former mayor Derek Corrigan voted out, Jordan and Johnston have remained loyal to the former mayor, while the rest of their former slate has aligned with Hurley. The fissure had already been apparent by early 2020, when Jordan, Johnston and the since-deceased councillor Paul McDonell split from the long-ruling Burnaby Citizens’ Association.

Little has changed in the months that followed, with the schism showing up in some votes, while council has voted as one in others. Since the BCA defection, discussions in council chambers have remained largely civil – if they’re had at all. Jordan has suggested in the past that she and Johnston have often been steamrolled by council, with votes approved by the majority coalition without responding to the concerns they have raised.

But only a handful of times have comments been directed at other councillors rather than on issues.

In this case, however, animosities appear to have surfaced, with councillors’ comments getting more personal and accusatory.

In the December council meeting, Jordan opposed the proposal because it “sets a terrible precedent” for the Royal Oak plan and for the whole city.

The proposal is for “spot zoning for a huge increase in not only the density but also the use,” Jordan said. “This is ridiculous, and I think it’s giving a huge financial benefit to the proponent by giving them such high zoning in an area where the property values are based on a much lower level of zoning.”

Johnston, a fellow independent and ally of Jordan, also voiced his opposition to the proposal in December, noting the BCGEU had previously sought an amendment for three of the Palm Avenue lots 11 months prior.

According to the minutes of the Jan. 28, 2020 planning and development committee meeting, the BCGEU was told “the city does not support/practice site specific rezoning,” and the matter was referred to staff.

“All of a sudden we have a rezoning application on the agenda this evening, and it just smells a little fishy,” Johnston said.

A two-way street

The B.C. Government and Services Employees' Union is looking to move from its current Lower Mainland headquarters in Vancouver to a new location in Burnaby. By Jennifer Gauthier/Burnaby Now

The B.C. Government and Services Employees' Union is looking to move from its current Lower Mainland headquarters in Vancouver to a new location in Burnaby. By Jennifer Gauthier/Burnaby Now

Jordan later questioned to the NOW why the zoning amendment had returned to council less than a year after it was turned down by the committee. She notes the mayor was the only elected council member to be endorsed by the BCGEU, which only endorsed two other candidates in that election.

Hurley, however, says the January 2020 proposal and the December 2020 proposal were miles apart in terms of zoning, with the former calling for a 30- to 40-storey tower on a much smaller site. (Sales on two of the lots were finalized three days and 10 days after the initial committee meeting, according to BC Assessment.)

And the rezoning is being considered, Hurley adds, because, with “affordable” child care attached and at least half of the units slated for below-market housing, it is extraordinary in what it offers, irrespective of who is putting forth the application.

“There’s no other proposal in the city that would bring that kind of rental anywhere,” Hurley said. “If anyone else wants to come forward with the same mix of buildings, we will look at it very, very strongly. Any organization.”

Any upzoning can benefit the owner of a property to some degree, Hurley notes, but in this case, “all that money is going back into the rental market.”

Finch and Hurley point out that Jordan voted in favour of Metrotown rezonings that gave massive land value increases to developers, with the Metrotown community plan upzoning vast swathes of land largely occupied by older, affordable low-rises.

“(Upzoning) happened all over Metrotown all over the last 10 years, … and people made profits. Individuals made profits, and the only ones who suffered were renters,” Hurley said.

“Maybe Coun. Jordan’s OK with individuals making big profits, but the ones that suffered because of that upzoning … were renters who were told they had to leave Metrotown.”

The BCGEU and others rallied against the move at the time, saying that, without protections for renters, it would cause a land rush to buy up more affordable low-rises to flip into towers and lead to more demovictions.

Since the BCGEU launched its Affordable BC campaign, Finch says, a lot of its criticism was aimed at Corrigan and his allies on council, including Jordan and Johnston.

“They came under intense scrutiny and criticism for their stances against affordable housing,” Finch said, adding their criticism aimed at the BCGEU proposal “seems to be a direct response to that.”

And this dispute may cost Jordan and Johnston key endorsements.

Endorsements at risk

Finch said Jordan has since been contacted by the New Westminster and District Labour Council about her vote on the BCGEU proposal.

“Basically, it’s a process to look at withdrawing their endorsement of her,” Finch said.

In a brief email statement, labour council secretary-treasurer Janet Andrews gave sparse details on the matter.

“The NWDLC endorses candidates for municipal office we believe share our values, and we endorsed Colleen Jordan as a member of the BCA in the 2018 cycle. If concerns are brought to us from an affiliated union or delegate between elections they are addressed,” Andrews said, pointing to the labour council’s website for more background on the labour council.

Jordan says she has gotten a meeting request from both the labour council and the BCGEU, but notes she will not be meeting with the latter.

“I have never, and will never, meet with a developer alone and outside of the formal city council venues about a current in process rezoning request,” Jordan said in an email. “In this case the GEU is just like any other developer.”

Follow Dustin on Twitter: @dustinrgodfrey

Send him an email: [email protected]