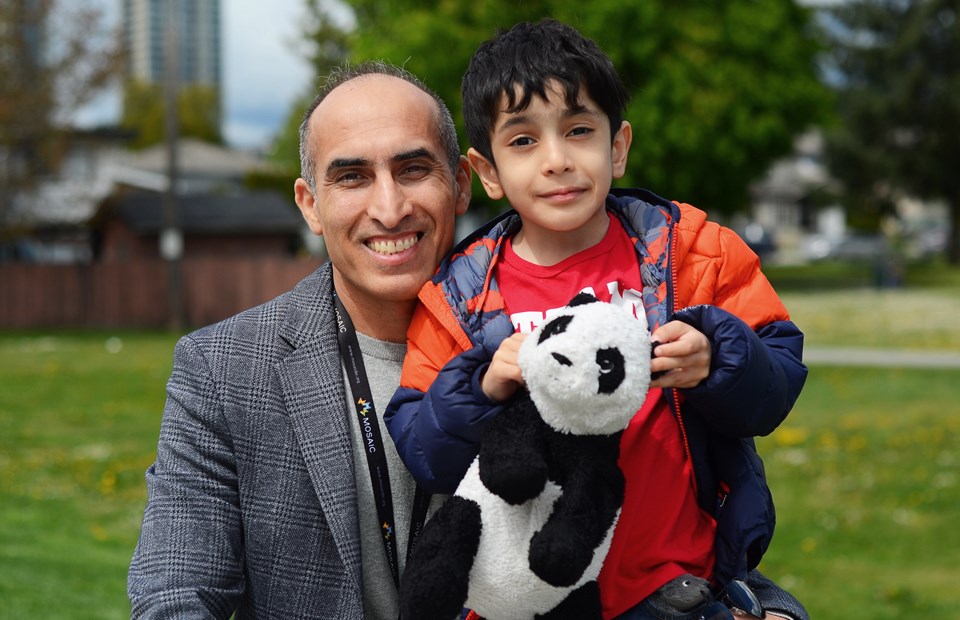

Burnaby resident Zarif Akbarian was nine years old when he decided he wanted to be a doctor when he grew up.

Many of the family members he lived with in his native Afghanistan were sick but had limited access to health care, he said.

“I could see people are suffering because of sicknesses and diseases they had, but there wasn’t really a cure for them,” he said.

He said he had been forced to watch both his grandmother and grandfather suffer for a long time before they finally died of cancer.

So, years later, after he graduated from medical school and started working as a GP, he said every day was “joyful.”

“Because, for a doctor, nothing is better to see than happiness and happy face and relief,” he said.

That all came to an end when Akbarian and his family had to flee the country in 2015.

Since arriving in B.C. as a refugee, Akbarian hasn’t been able to work as a doctor because he doesn’t have a licence.

He has all but given up on the costly and difficult process of getting it – but that hasn't stopped him from putting his medical background to work in the battle against COVID-19.

Help for newcomers

He has been working part time as a health-promotion coordinator with MOSAIC, a Lower Mainland settlement agency, and volunteering with Health Navigator, an initiative that helps refugees and other newcomers who don’t speak English navigate the Burnaby Division of Family Practice’s online COVID-19 self-assessment tool.

“It’s really been a great time for me to get back on track and start to review my medical stuff and also use my education,” Akbarian said.

Since he is plugged in to his own local Afghan community and also knows languages spoken in Iran, Azerbaijan and Tajikistan, Akbarian has become a valuable source of information about the novel coronavirus itself, local COVID-19 updates and the latest public health orders for people who wouldn’t otherwise have access because of language barriers.

“They have many questions regarding the disease itself and also regarding the other implications, financial and school for their children, work, housing,” Akbarian said. “And also they are worried about their extended family members back home.”

Akbarian said newcomers listen to him and trust the information he passes on, in part because of his medical background.

“In our community, people with medical education that they call doctors, they have very special place in people’s life and people’s social interactions, so people really, really trust and believe doctors, and everything the doctors say, it’s scientific and based on the facts,” he said.

Akbarian said he’s grateful to MOSAIC for recognizing his potential as an international medical graduate (IMG) to contribute to the COVID-19 response, but he is still a long way from ever practising as a doctor again.

“It’s a very lengthy and expensive process,” he said. “And for a refugee person like me, I need to also support my family.”

Akbarian is not alone.

Untapped potential

The COVID-19 pandemic, which prompted the government to re-register retired doctors and nurses in case they were needed during the crisis, is once again drawing attention to the untapped potential among internationally trained doctors in the province.

The College of Physicians and Surgeons of B.C. is currently in the process of crafting bylaw amendments that would create a new “associate physician” class that would allow qualified IMGs “to work under supervision in acute care settings to increase capacity and service delivery.”

The proposed changes don’t go far enough, though, according to nearly 1,700 people who signed a recent petition calling for IMGs to be allowed to work during the pandemic.

But Doctors of BC president Dr. Kathleen Ross said it comes down to keeping patients safe.

“We definitely do support the integration of international medical graduates into our workforce plan,” she told the NOW, “but we have to be very respectful of the college’s minimal licensure requirements to ensure that patients are safe.”

That being said, Ross said she feels for internationally trained doctors and the challenges they face.

She said she has seen from her own practice the value they bring to the community, with many – like Akbarian – volunteering support.

“But volunteering support isn’t necessarily optimizing our use of a physician’s skill set,” Ross said.

She said she hopes the college’s bylaw changes will allow those who have the right skills a chance to use them.

It’s unclear whether Akbarian will be among them

He said he has put his hopes of working as a doctor in B.C. on hold for now, waiting for a path forward – and a way to afford it.