Nine hundred and seventy – that’s how many people were reported missing in Burnaby last year and according to the department’s new missing persons unit coordinator, the numbers are on the rise.

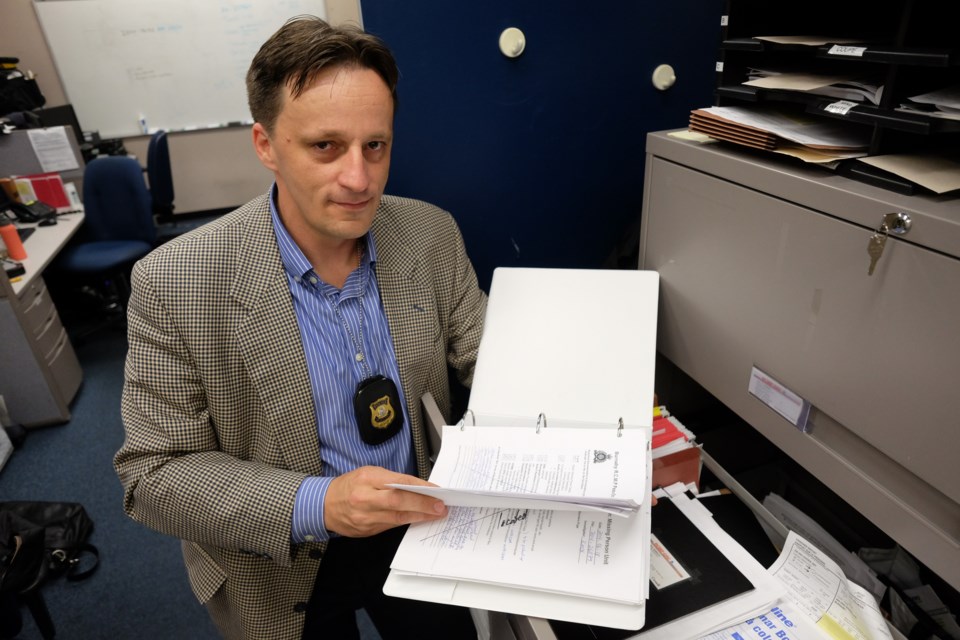

Cpl. Antonio Guerrero oversees a four-constable plainclothes unit charged with investigating the city’s missing persons files. The unit is a dual-duty unit that also handles domestic violence investigations, which has its own coordinator specific to those cases. The department combined the two types of investigations because of their high-risk nature but Guerrero expects that one day, the units will be separated.

“Especially as this trend, this foreseeable trend, continues. As far as calls for service increasing, our future goal is to have two separate units,” he said.

Guerrero said one of the reasons why the number of missing persons reported is on the rise could be because of two medical centres within Burnaby’s borders.

According to Guerrero, 277 people were reported missing from Burnaby Hospital’s mental health unit and the Burnaby Centre for Mental Health and Addictions last year – nearly 29 per cent of all reported missing persons in Burnaby.

“These are ones that are difficult to investigate despite the help of family and help from our other partners,” he said. “Those people tend to lead a certain lifestyle that’s high-risk and on top of that they left voluntarily and they don’t, in most cases, want to be found by the police. The majority of the time they do return, but at the same time we have to make sure we follow our protocol and go through the investigation as thoroughly as possible just to prevent … a negative outcome. We just want to make sure we treat everyone with the appropriate resources and time.”

The same can be said about youth running away from group homes, Guerrero added, but he was unable to provide the NOW with how many youth from group homes were reported missing.

In fact, Guerrero couldn’t provide any specific data in regards to the demographics of missing persons files handled by the department because he doesn’t have access to the data – it is compiled by a civilian staff member separate from his unit. Guerrero added in an email to the NOW that due to a shortage in “civilian staff specializing in that field, a complete report would not be available at this point in time.”

In Canada, demographics on missing persons are tracked by the National Centre for Missing Persons. According to the centre, in 2013 there were 14,193 people reported missing in British Columbia – Burnaby’s 970 reports accounts for nearly seven per cent of the provincial total.

Of the 14,193 reports, 7,262 were adults and 6,931 were children. The data also shows that more than 50 per cent of all files are closed within 24 hours of the reports being made, while more than 85 per cent are closed within one week.

Guerrero agreed most of the cases are solved quickly and his four constables typically only take over an investigation if the case is deemed high-risk.

Children, seniors, physically disabled people, and mentally and medically ill people are all considered high-risk because of the specific needs they often have, Guerrero said. It’s up to the responding officer to review the case and decide whether or not it should be upgraded to high risk.

“The uniform investigator … speaks to their supervisor and goes through those risk assessments. Would this constitute as a high-risk person, in our definition? When they’re identified as high-risk missing, then these four investigators will get engaged and they’ll take over the file,” he said.

In the initial steps of an investigation, the patrol officer dispatched to the call will interview family and friends of the missing person along with the person who made the report.

Despite the rise in missing persons reported, the Burnaby RCMP does not share information on each individual case with media or the public unless the case is high-risk or if all avenues of investigation have been exhausted. Once this point is reached, and only then, will Mounties put out a release through media, Guerrero said.

“I prefer it this way because, obviously, I’d like to see us do the background work first before reaching out,” he said.

Further background work is the responsibility of the assigned officer. It’s up to them to determine any risk factors such as medical issues, suicidal tendencies or possible parental abduction, Guerrero said.

“We’ll also ask about what kind of lifestyle they lead? Are they involved in the gang lifestyle? The drug trade? Do they have a history of going missing? That’s important,” he said. “And if so, how long have they gone missing before they come back?”

If an individual is considered high-risk,then the four specialized investigators from Guerrero’s unit take over. Often that means they will reinterview family and friends of the missing to ensure nothing was missed during the initial stages of the investigation. Guerrero said it’s common for people to remember new details about a person’s disappearance as time goes on, which is why speaking with family and friends a second time is so important.

“We’re always in open communication with family members too, because sometimes they’ll forget … and they’ll contact us,” he added.

If the investigators hit a wall in the case, that’s when a bulletin will be released to the public through the media, which almost immediately generates tips from the community. It’s up to the investigators to follow up on each and every tip that comes in just in case it could lead to a break in the case, Guerrero said.

“We will follow up on every single one but we do look at them as far as what is the content of the tip. If a person indicated they saw a person that’s possibly our missing, but they’re very specific on what they’re wearing and it fits our person, obviously that would be more of a priority,” he said.

Currently, there are seven missing persons cases that remain unsolved in Burnaby – Angela Arseneault, Bryan Braumberger, Zeyu Qu, Asim Chaudhry, Adam Richard Myers, Guifeng Tong and Lon Batchelor.

Still missing

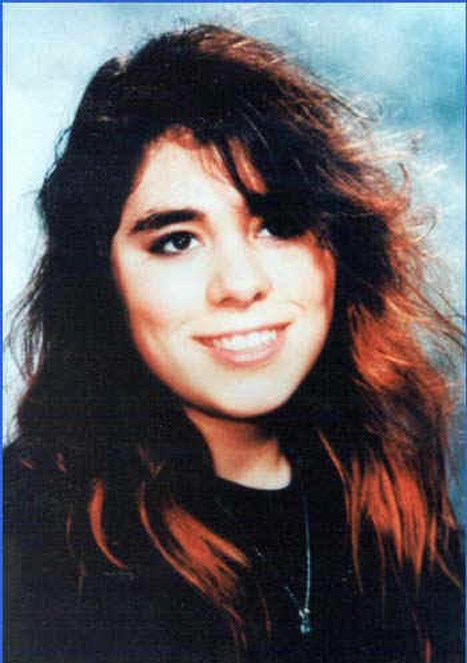

Angela Mary Arseneault

Arseneault was reported missing on Aug. 29, 1994. She was last seen on the evening of Aug. 19 boarding a bus in Vancouver to her home in Burnaby.

She was born May 20, 1977, and was 17 years old when she disappeared. She is 5-6 and weighs 150 pounds. She has a scar left inside knee about an inch long and two tattoos, one of a rose on her right ankle and another of a Chinese symbol on her left shoulder, which reads “Rock and Roll.”

Bryan Braumberger

Braumberger, 18, was last seen leaving his friend’s home in New Westminster in the early hours of May 31, 2007. According to previous reports, Braumberger told his friend he had to work the next morning. That was the last time anyone ever saw him.

He never showed up for work at Maxwell Paper in Coquitlam the next morning and he hasn’t been heard from since.

When Braumberger’s parents, Ron and Janice, returned home the evening of June 1, there was a message from the George Derby Care Centre on 16th Avenue. The message said Bryan’s car had been found in the parking lot and someone needed to pick it up or it would be towed. They quickly alerted police and reported their son missing.

Despite a reward of $30,000 for information on what happened to Braumberger, no new clues have been revealed.

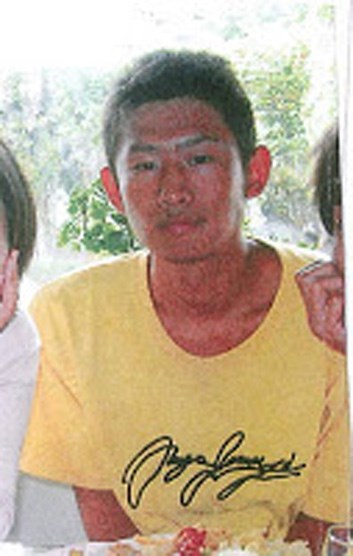

Zeyu Qu

Known as a happy young man, Qu became more quiet and reserved during the days leading up to his disappearance in 2009, according to police.

The international student from China was in Burnaby studying English and on Aug. 9 he left a note for his home-stay family that said he would be back in a few days.

But he never came back.

At the time, police suspected the 18-year-old had taken some of his belongings with him on Aug. 9, possibly carrying the items in either a large blue backpack or yellow carry-on suitcase.

Qu was not believed to have anything to do with drugs or alcohol. His family in China was contacted but couldn’t travel to Canada. Qu was staying in a home in the 6600 block of Broadway.

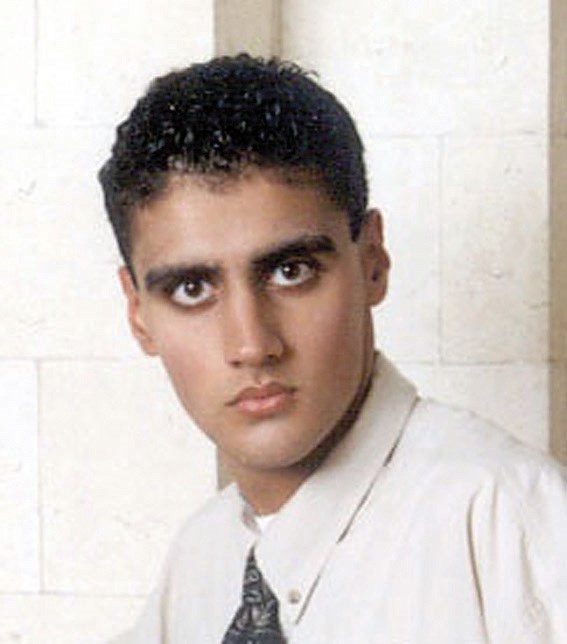

Asim Chaudhry

Chaudhry was always a happy-go-lucky boy. Close to his mother and a good student, the 24-year-old became increasingly anxious and melancholy during his time at Simon Fraser University, according to police. By the time he crossed the stage at convocation, Chaudhry was “agitated and nervous.”

Chaudhry’s bad mood eventually dissipated and soon he was back to his old self, according to his mother.

“Before, he was very, very stressed out or depressed,” Chaudhry’s mother Mansura told media at a press conference in 2008. “In the last three months, two months to three months, he changed. … He was willingly going everywhere with me and seemed happy.”

On July 20, 2007, Chaudhry left his home. He told his family he was on his way to SFU to study in the library.

Police have no record of Chaudhry ever being at SFU that evening. They did determine he met up with an old friend at Brentwood Mall. Together, the two friends had ice cream at the McDonalds before going their separate ways at the Production SkyTrain station around 10 p.m.

At the time, there was nothing to indicate Chaudhry was involved in any criminal activity or partaking in drugs or alcohol.

Adam Richard Myers

Last seen on Oct. 4, 2010 living in his Metrotown apartment. His family has not heard from him since, but did not report him missing right away. Myers was 25 years old when he went missing. He is 5-8 and 190 pounds with brown hair and eyes. Last seen wearing a black winter jacket with blue jeans and white runners.

Lon Batchelor

Batchelor has been missing since July 1, 2013 and was previously of no fixed address. He was reported missing by his family.

Batchelor, 43, is 5-8 with a medium build, with short dark brown hair. Part of his right hand pinky is missing and he is known to wear glasses.

Guifeng Tong

Tong was last seen on Jan. 16, 2013 in North East Burnaby. Despite an extensive search of the area, police were unable to locate her.

Tong was last seen wearing a red hooded rain jacket, black pants and black shoes. The 66-year-old Asian woman is about 5 feet tall and weighs about 100 pounds with a slim build.

Tongs is known to walk and take transit, and often picks mushrooms and collects recycling bottles. She is also known to frequent the Burnaby Mountain and Burnaby Lakes areas. Tong only speaks Mandarin, and has no known medical issues.