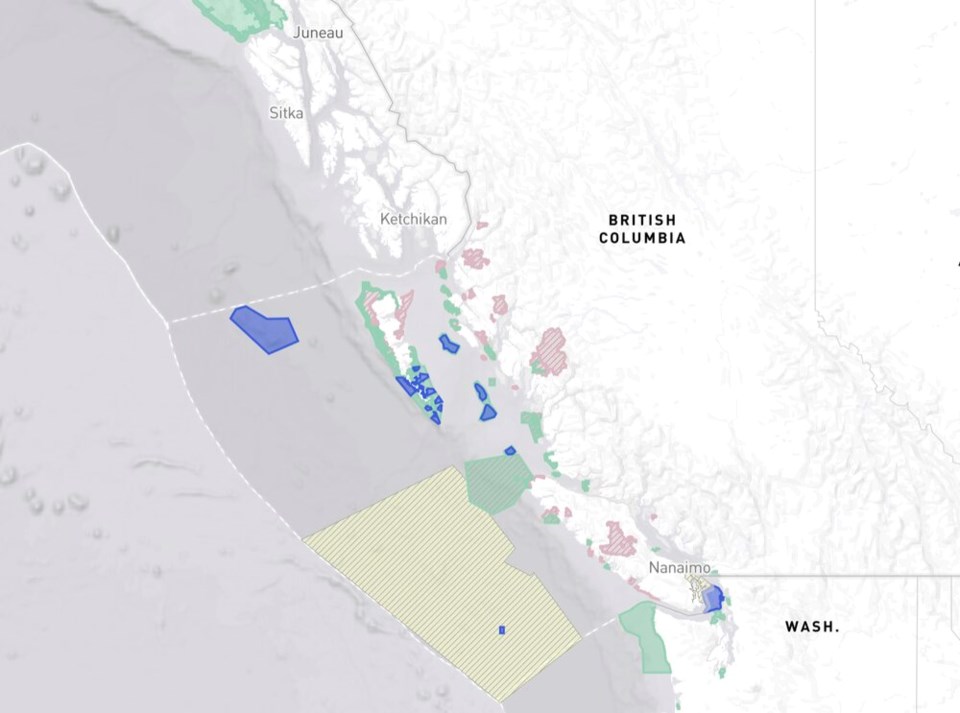

A plan to create a vast network of marine protected areas stretching from Vancouver Island to the Alaskan border inched closer to reality this Thursday after the governments of Canada, British Columbia and over a dozen First Nations released a draft plan to the public.

If enacted, the marine protected areas (MPAs) would protect nearly a third of the Northern Shelf Bioregion — a 100,000-square-kilometre tract of ocean also known as the Great Bear Sea.

The network would help Canada achieve its own targets of conserving 25 per cent of the country’s oceans by 2025 and 30 per cent by 2030 — minimum thresholds scientists say are required to reverse biodiversity loss by 2050. While the proposed network would inch Canada 0.2 per cent closer to those targets, it would also create a blueprint for other sensitive marine ecosystems under threat across the country.

“Even though we've had years and years of delay, this is definitely the closest we've ever come,” said Kilian Stehfest, a marine conservation specialist with the David Suzuki Foundation.

“It’s really the pilot for other regions of Canada.”

The first marine protected area in Canada was established in 2003 around the Endeavor Hydrothermal vents, 250 kilometres off the coast of Vancouver Island.

Since then, 13 more swaths of ocean have been put under legal protection in a bid to preserve everything from Pacific glass sponges, to roving blue whales off Canada’s Atlantic coast, to Arctic feeding and breeding habitats for polar bears and seals.

Alone, scientists say no single chunk of the seabed can protect ecosystems that span entire coastlines or oceans. A network of protected ecosystems, however, could offer ocean-trotting whales or salmon a refuge in the same way intact wetlands give sanctuary to migrating birds.

That's important in B.C., where the province's coastal ecosystems face a complicated set of pressures from a variety of human pressures — and increasingly, climate change.

An 'insurance policy'

Since humans started burning vast quantities of fossil fuels in the Industrial Revolution, the world’s oceans have helped cushion the effects of a warming climate by absorbing and storing heat. But many ocean creatures can only handle so much warming before they die or are forced to move to cooler waters.

Another problem for the web of marine life comes from increasingly acidic oceans.

When carbon dioxide mixes with sea water, the gas transforms into carbonic acid. The more acidic the ocean, the less calcium carbonite it can hold — a key ingredient sea creatures use to grow shells and coral species use to expand their life-supporting reefs.

Over the past 250 years, human-produced carbon dioxide has led to a 30 per cent spike in ocean acidity, threatening the survival of entire marine ecosystems that require the right pH balance.

No amount of MPAs will reverse climate’s impact on ocean life, but they could help limit local threats from a number of human activities, including fishing, aquaculture, shipping traffic, tourism, oil and gas extraction, and coastal development.

“[It’s] a bit of an insurance policy,” said Stehfest.

This isn't the first time a network of MPAs has been deployed as a hedge against threats to the ocean.

In California, early research has shown its network of 124 MPAs — together spanning over 16 per cent of state waters — has helped to boost stocks of rockfish and beds of endangered black abalone since they were introduced a decade ago. In one group of islands under protection, the density of fish species was 50 per cent higher than outside of the network.

Protecting swaths of ocean could also generate millions of metric tonnes of food that wouldn’t be available without them.

One 2020 study found that strategically expanding a global network of marine protected areas by five per cent could increase future catches by 20 per cent.

The proposal to expand B.C.’s MPAs would double the current number of MPAs. The 30,000 square kilometres of protected waters would cover an area equal to three per cent of all Canadian waters in the Pacific.

Designed to safeguard biodiversity, special natural features and fish stocks, the protected seas are also meant to contribute to the social and economic health of the region.

Fishing groups say they aren't being heard

Not everyone is optimistic about the promise of a coast-wide network of protected ocean.

Many communities up and down the coast have not been properly consulted, according to Owen Bird, executive director of the Sport Fishing Institute of BC.

He worries that the network will lock out coastal residents from important resources they need to survive and turn the ocean into “preserves or natural parks.”

“The worst-case scenario is something that is preservationist, where there’s only certain kind of access or only First Nations have access to huge swaths,” said Owen. “That’s kind of a disaster for those small communities.”

Sport fishing employs around 9,000 people in B.C; another 250,000 to 300,000 people hold tidal angling licences at any given time, says Bird.

B.C.'s commercial fishery, meanwhile, has faced devastating closures in recent years. In 2021, a ministerial order from Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) said it would shut 60 per cent of Pacific salmon fisheries.

Watershed Watch Salmon Society's Greg Taylor said fisheries managers have not since met that threshold of closures. But due to a dwindling fleet, limited catch windows and interception of Canadian-bound fish in Alaska, catching a lot of fish can be hard — even during healthy sockeye returns like that seen on the Skeena River this year.

“It’s over,” said Taylor. “The commercial fleet is a shadow of what it was.”

Salmon, however, isn't the only commercially viable catch in B.C.

Emily Orr, business agent for the United Fishermen and Allied Workers' Union, said by setting targets to protect 25 per cent of Canada's oceans by 2025, the federal government has put "undue pressure" on fishery closures.

“The death by a thousand cuts analogy really applies here,” she said.

In the lead-up to the draft protection plan, Orr said fishery groups have been largely left out of consultation until it’s too late to make any difference.

Both Bird and Orr said they hope that will change with the latest round of public input.

Responding to industry concerns, a spokesperson for the proposed MPA network said it would “help create more stability and economic security for coastal communities” and contribute “to a strong future for B.C. fisheries.”

Starting in Sept. 15, the draft plan will open to public consultation until the end of October 2022. First Nations and others living along the coast can provide input on the plan through an online survey, open houses and webinars — all available at https://mpanetwork.ca/engage.

A full report is expected in the spring of 2023. Once the blueprint, known as a Network Action Plan, is endorsed, several new patches of ocean could be officially protected starting in 2025.

Canada playing catch-up

Across Canada's Atlantic, Arctic and Pacific oceans, 14 MPAs are safeguarded under the Ocean's Act, together accounting for six per cent of the country’s coastal waters.

But according to the Marine Conservation Institute, which tracks marine protected areas across the world, only 0.3 per cent of Canadian coastal waters are either fully or highly protected.

Compared to other nations, that figure places Canada tied in 27th spot, far behind countries like the United States, Australia and the United Kingdom. Even Russia, with its massive Arctic coastline, has done a better job in protecting its oceans, according to the institute.

Part of the gap between government and independent assessments comes down to quality of protection.

A 2021 report from the B.C. chapter of the Canadian Parks and Wilderness Society (CPAWS-BC) found that more than 60 per cent of the province’s marine protected areas were not effective in protecting biodiversity.

Kate MacMillan, oceans conservation manager for CPAWS-BC, said many protected areas amount to “paper parks” that don’t have adequate protection from trawling, or in some cases, still have open oil and gas permits on the books.

If Canada has a hope of meeting its marine protection targets in 2030, it needs to take “swift and decisive action” to improve its own standards, she said.

A spokesperson for the MPA network told Glacier Media it has taken over a decade to create the marine network to ensure “due diligence.” The current phase of public consultation, said the spokesperson, will be crucial to “work through issues” and “ensure the future regulatory processes are efficient and comprehensive.”

Still, said MacMillan, “the delays in the process have been concerning.”

“The longer you delay in getting these sites designated means that the impacts on these areas are just going to continue.”

Or as Doug Neasloss, chief councillor for the Kitasoo Xai’xais Nation, put it: “I think we’re light years behind.”

Neasloss recently returned from a global UN Oceans Conference in Portugal, where he said he was struck by how many nations competed to protect a greater share of their oceans.

Back home on B.C.’s central coast, his community has sat at the negotiating table with the federal government for more than 15 years to come up with a plan to conserve Canada’s oceans.

After so many missed deadlines, Neasloss said “we have nothing to show for it.”

The Kitasoo Xai’xais way of life is at stake, he said.

Tired of waiting, First Nation protects marine 'breadbasket' alone

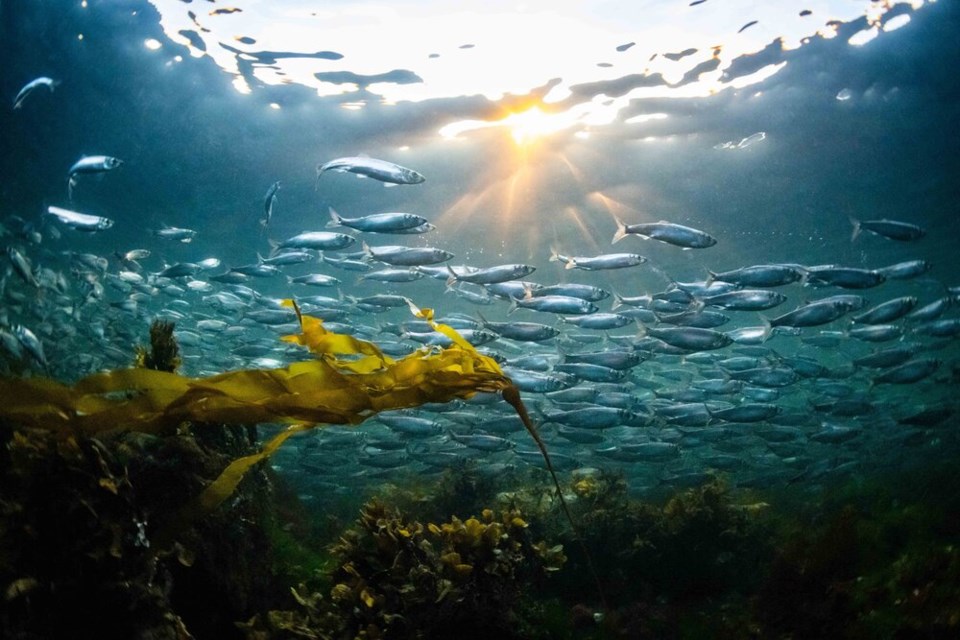

At Kitasu Bay, people have harvested food for generations.

At some times of the year, they set tree branches under water to collect herring eggs during the spawning season. When they are later pulled into a boat, the dark green swashes are covered in a thick mat of white eggs.

“That brings in all the halibut and all the ducks, all the seals and sea lions and rockfish,” said Neasloss, describing the bay as the nation’s “breadbasket.”

“It’s what feeds and sustains our community.”

But in recent decades, the abundance once seen has declined. Abalone has vanished and the salmon run this year has been among the worst Neasloss has seen.

“We couldn’t wait anymore,” he said. “Our nation just said, ‘Listen, we're tired and we're frustrated waiting for government. So we're gonna take it upon ourselves to protect our own areas,’” he said.

On July 21, the Kitasoo Xai’xais announced they would be establishing their own nearly 35 square-kilometre marine protected area in Kitasu Bay.

The First Nation is still consulting industry and gave the federal and provincial governments 90 days to respond to its MPA declaration.

In the meantime, the community is patrolling Kitasu Bay, largely with its eight guardian watchmen, who ensure outsiders aren’t harvesting species that need time to recover.

As environmental stewards, the watchmen are not armed. Instead, they’re trained in conflict de-escalation. Still, some situations have spiralled out of control.

Neasloss says that about five years ago Fisheries and Oceans Canada opened up the herring fishery in Kitasu Bay. At the time, Kitasoo Xai’xais’s own experts and leaders assessed that fish stocks weren’t at levels that justified opening their waters to fishing.

“We sent a letter and said, ‘Don't go to Kitasu Bay.’ And what did they do? The whole fleet went to Kitasu Bay,” said Neasloss.

After an emergency community meeting, a delegation delivered the letter to each fishing boat that had come into the bay, asking them to leave to help the fish recover. Within a few minutes, most boats motored away respectfully and without incident.

“A few said, ‘Screw you guys, I'll fish wherever DFO says I can fish,’” said Neasloss.

“So we basically said, ‘Well, it's gonna end one of two ways: Either you pull up anchor and leave peacefully or we come out here with 50 boats and we drag you out.’”

The remaining boats left.

Such incidents don’t happen regularly, but coming together as a community to eject poachers or uninvited fishers remains “a last resort,” said Neasloss.

“Verbal Judo” and focusing on ways to invite people into the community in positive ways, is the preferred option, he said.

“We want people to come to our territory and make a living as a commercial fisherman or as a recreational fisherman. But yeah, there's some areas that we need to look at stronger measures,” he said.

CORRECTION: A previous version of this story said the draft MPA plan would open to the public Monday. The plan, in fact, was released Thursday, Sept. 15.