Have you ever wondered what happens to an astronaut's health when they return from space?

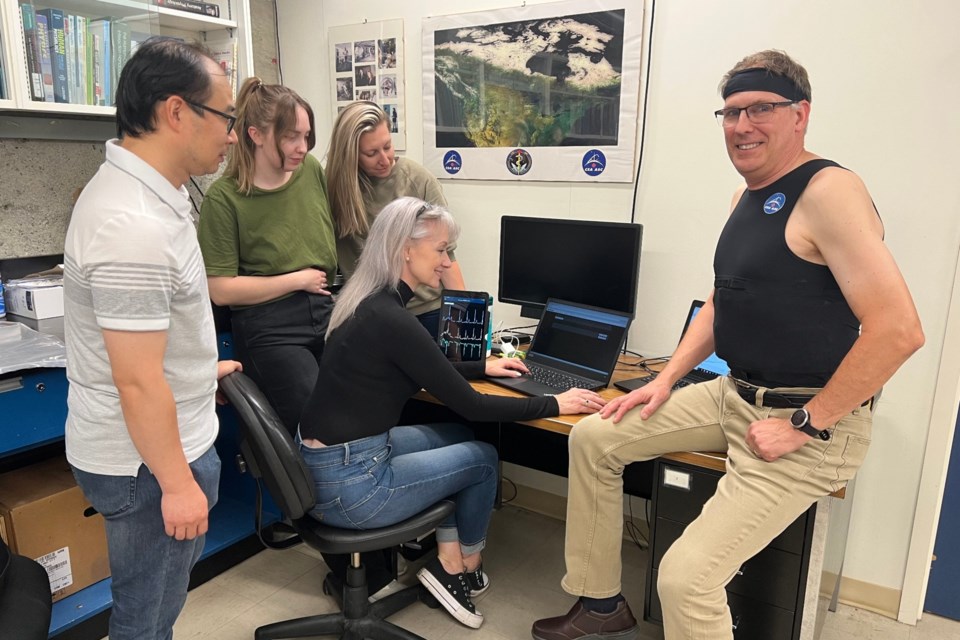

A research study, Cardiobreath, spearheaded by Simon Fraser University (SFU) professor Andrew Blaber has been launched to answer that question.

The team, which includes Blaber, researchers from SFU and University of North Dakota, are in Houston, Texas, until Monday, Sept. 18 to observe how the astronauts' cardiovascular and respiratory systems interact with their blood pressure control systems once they return to earth and provide inference for future space missions.

Human bodies, of course, are accustomed to life on Earth.

But in space, their cardiovascular systems and respiratory systems adapt to a new weightless environment, leaving the astronauts returning with health issues after.

Those returning have to re-adapt to the world — get their reflexes and heart pumping the right way — but it doesn't always happen very quickly.

"Astronauts in space face unique challenges with blood flow and pressure due to lack of gravity, leading to potential fainting spells upon return to Earth," Blaber told the NOW.

He noted the heart is located above 70 per cent of the human body, and a lot of our blood volume is in the lower part of the body.

"So when astronauts come back and they stand, the reflexes that tells them to do those compensation events don't happen. So they don't get blood to the brain and then they can faint."

This study, funded by the Canadian Space Agency, began with early data collection and will aim to study 14 astronauts’ cardiovascular systems — with four members' observations culminating Monday.

How it works

The study employs a Bio-Monitor shirt to measure the impact of exercise on astronaut health before, during and after they return from the International Space Station.

Astronauts wear the shirt to collect data on blood pressure, breathing, heart rate and overall functioning of the heart muscle through electrocardiogram monitoring.

The first set of tests taken on earth are measuring how their systems respond to gravity while wearing the Bio-Monitor:

- Blood pressure and breathing control when standing up quickly from lying down

- Moderate exercise for 20 minutes

- Five minutes of standing

While in space, astronauts will be monitored at rest, during warm-up and while exercising for 20 minutes using a cycle ergometer with Vibration Isolation Stabilization (CEVIS) space exercise bike.

These exercise tests are repeated when the astronauts return to earth.

Blaber acknowledged the data of recovery time for astronauts when they return is few and far between, but that's what the project hopes to study.

"Right now, the vast majority of astronauts stay [in space] for about six months," he said.

"There are a few that are staying a year because they want to see those longer effects… because if we go to Mars, it's going to be at least a year. So we need to understand that but the ones that we're looking at typically will be up around six months."

Astronauts experience severe posture problems after just eight days in space, Blaber added.

"They [astronauts] were up somewhere up for eight days and they came back with severe posture problems… we don't really know when this slows down."

Findings and the next steps

The findings from the study will help develop individualized recovery plans for astronauts.

"We [want to explore] what types of exercises we may have to use to fix it, whether there might be some drugs or other types of therapeutics that we can have the astronauts take to stop the deterioration of the nervous system in the reflex," Blaber said.

As well, the results could potentially help elderly patients who are recovering from a long hospital stay as effects of prolonged bed rest changes blood flow patterns and can increase fatigue and cause fainting.

"We give them these therapeutics we learned about from the astronauts and have them do that while they're in bed before they get out of the hospital so they don't have problems when they're discharged," he added.