Mike Beamish worked as a sports reporter for the Vancouver Sun for 43 years before retiring in 2017. In this submission for the North Shore News, he looks back at the death of race car driver Greg Moore 20 years ago, a loss still felt by many media members who covered the popular athlete during his career.

Even two decades after his loss, the memory of race car driver Greg Moore still exerts force and pull.

His crash and death – at the California Speedway, on Oct. 31, 1999 – is one of those moments in sport that remain etched in time for many Canadians, the unimaginable flip side of Sidney Crosby's Golden Goal, Jose Bautista's Bat Flip or Kawhi Leonard's Corner Shot.

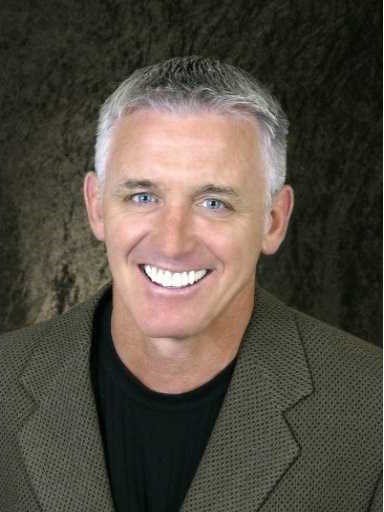

To capture the competitive genius of athletes through print, voice or video is one of the challenges for reporters and broadcasters. Yet, there remain moments when words are a struggle, or don't come at all. Twenty years later, it's still a reach for Barry Houlihan, semi-retired from a real estate career in North Vancouver and Maple Ridge.

"I couldn't tell you what I did the following week (after the crash) because I was in a daze for days. Just in total shock," says the 66-year-old Deep Cove resident. "It's something I don't like to look back on. It's avoidance or something."

To prove his point, Houlihan doesn't remember being in the company of the Moore family at a memorial service in Maple Ridge, four days after the tragedy. Hundreds of mourners showed up in Moore's hometown, the day after a "private" memorial in downtown Vancouver drew 1,200 heavy hearts, packed into St. Andrew's-Wesley United Church.

Houlihan was very close to Moore's family, his dad Ric and mom Donna, to the point where he became a guest for Super Bowl parties at their home. He was stuck somewhere between being a loyal friend and the professional detachment of a reporter and broadcaster.

In the 1980s and ‘90s, when he worked as a sportscaster for CKVU-TV in Vancouver, then BCTV, Houlihan supplemented his income by doing freelance stories for the Maple Ridge Times. He documented Moore's rise from go-karts, through the ladder of North American open-wheel racing to Indy Lights, the AAA farm league of CART (Championships Auto Racing Teams) where the driver's uncanny knack of pushing the envelope to the max, without exceeding it, drew others into his orbit.

Many in the Vancouver sports media had only passing interest in motorsport. That changed with the advent of the Molson Indy Vancouver in 1990 and the eventual graduation of a homegrown hero to the series.

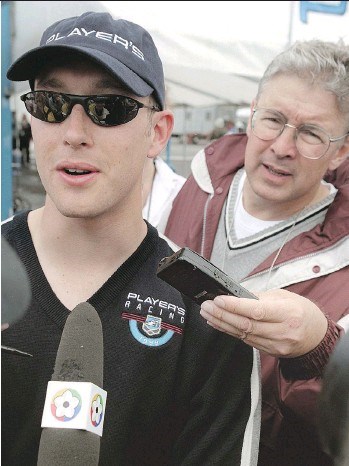

Fascination with the media-friendly Moore turned the disinterested into followers, if not confirmed gear heads. Before others did, Houlihan grew to appreciate the complexity of the cars, and the teamwork, courage and skill required to win.

"I knew squat about it before Greg came along," Houlihan admits. "I thought motor racing was boring as hell, just cars going round and round. But I learned a lot, just through osmosis. Greg was just a special case. He stood out – articulate, bright, good looking, mature beyond his years – the full meal deal."

Potential tragedy lurks at every motor race, and in 1999 CART was hit especially hard over a 51-day stretch. The series first lost rookie Gonzalo Rodriguez, in a crash during practice for a race at Laguna Seca, Calif., on Sept. 11. Then came Moore's wreck in the final event of the season, in a 500-mile race at the California Speedway. The next day, Nov. 1, Pro Football Hall of Famer and CART team owner Walter (Sweetness) Payton died from a rare liver disease.

It was a sombre time in one of the deadliest years in the sport – three fans were killed in the rival Indy Racing League by flying debris – since 1994, when three-time world driving champion Ayrton Senna and rookie Roland Ratzenberger perished during the same Formula One weekend at the San Marino Grand Prix.

Growing up, Moore had a poster of Senna on his bedroom wall and dreamed of competing one day on the same tracks as that mythical figure.

It was not to be.

Senna was 34 when he died, 10 years older than Moore. But the Canadian was so focussed, serious and talented that Autosport, the global motorsport publisher based in London, rated Moore as the 15th best driver never to have competed in Formula One. That determination was made in 2013 – fully 14 years after his death.

"Whether it's the seventh year, the 10th year or the 20th year (since it happened), when the calendar rolls around to Oct. 31, I shake my head," says Eric Stansfield. "His death was hard to take. It still is. To this day."

A former sports television producer in Vancouver, Stansfield was involved in a number of features and interviews with Moore during his career ascent. He now works in Kelowna, where Stansfield and his wife, Lynda, run a small business. There is a photo of Moore on the office wall.

"I remember him every day," Stansfield says. "He impacted people from all walks of life. For Canada to lose someone like him ... it was just a huge, tragic event."

As he enters his late 60s, Houlihan struggles with the grim legacy of an outstanding but short-lived football career, brought on by a horrific car accident.

He played three years as a running back with the Washington Huskies – in an era when Canadians playing at the NCAA Division 1 level was a rarity – and another season at Simon Fraser University. Selected by his hometown B.C. Lions as a territorial protection, he is another example of What If? Those two little words cut to the heart of the Greg Moore tragedy.

Houlihan, too, saw his professional dreams shattered at age 23, when he fell asleep at the wheel of his Pontiac Grand Prix. He spent nine weeks in hospital. His car was wrecked. So was his professional sports career.

"In the blink of an eye, it was over," says Houlihan, who was named to the B.C. Football Hall of Fame in 2015. "I still have a ton of residual damage from the accident and my football career (two knee and one shoulder replacement).

"My accident was just me being young and stupid. It's the greatest regret of my life. But I'm blessed to be here. With Greg, in the blink of an eye, it was over. That's something we're still coming to terms with."