When Adhel Arop learned she’d won a $50,000 grant from the TELUS STORYHIVE program to create a short documentary film, she danced with her friends.

The award will give the 21-year-old Burnaby resident a chance to pursue a passion project she’s been working on since she started writing it for a Grade 12 English class: the story of her family.

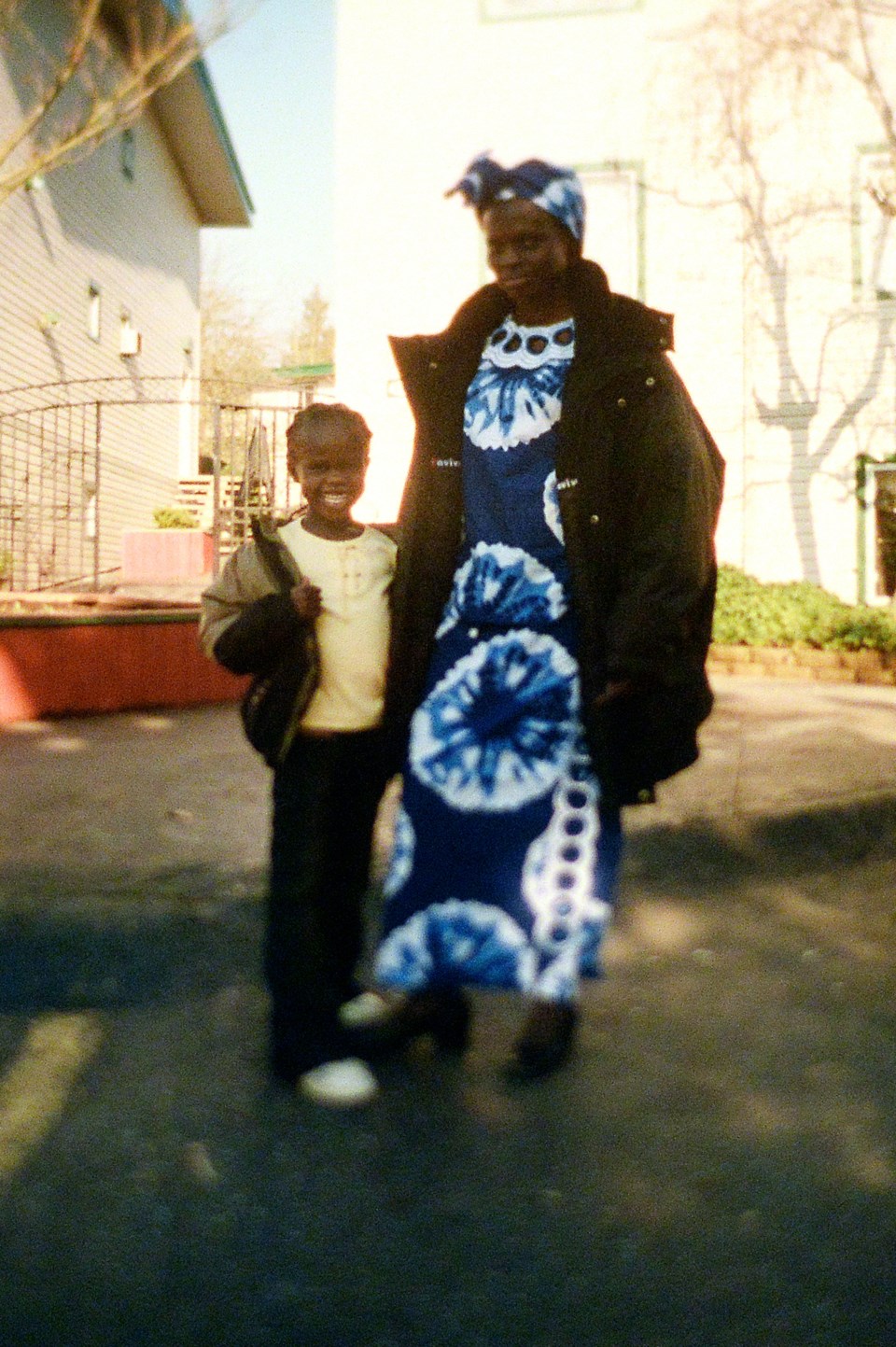

Her documentary, Who Am I?, is planned as a 15- to 20-minute exploration of her quest for her own identity against the background of her life as a South Sudanese refugee. Adhel’s mother, Amel Madut, was a teenage soldier in the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army. Amel survived the war and life in refugee camps in Ethiopia, Uganda and Kenya before bringing the family to Canada nearly 17 years ago.

Adhel will turn the lens on what those experiences have meant to her family and how they have shaped who she is today.

Adhel and Amel sat down with Burnaby NOW reporter Julie MacLellan to talk about the project.

* * *

Adhel Arop’s earliest memories are filled only with joy. She remembers playing, laughing, being surrounded by family and friends and love. And mom. Always mom.

She didn’t know what kind of turmoil was going on in the world around them all. She didn’t know what kind of unimaginable journey her mother, Amel, had travelled to bring Adhel and her siblings to this place, in Kenya – where Amel worked hard and prayed for the day they would be accepted as refugees to a land far away.

When the curious preschooler finally boarded a long-awaited plane to Canada, it was just an adventure.

“It was, hey, we’re on a plane, oh cool, what does this do?” recalls Adhel.

For Amel, that plane journey was much more than an adventure. It was salvation.

LIFE IN A NEW LAND

Life in Canada wasn’t easy at first. They were strangers in a strange land, with no idea where to go for the most basic of tasks – grocery shopping, banking, registering for school. And there was the language gap, too: the children had spoken Swahili at school in Kenya, and the family also spoke Arabic and Dinka, the major language of South Sudan.

Amel made sure they all learned English. She took two jobs to earn the money to support them all.

“I made my children, my siblings, not to lack anything,” she says. “Whatever I get, I have to spend it on them.”

To this day, Amel and Adhel are grateful for the support they found in their Edmonds-area apartment complex. There, immigrant and refugee families from all around the world – Somalia, Russia, Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, Ethiopia – built a community of Canadian newcomers.

The workers at Edmonds Community School were a big part of Amel’s support network in those early years. Edmonds and Byrne Creek Secondary School were key influences in helping the family settle in to their new life.

Education was always number 1 for Amel.

“I pushed them to go to school. I bring them here, I say, ‘This is a land of opportunity, you have to work hard,’” Amel says.

Adhel concedes she probably had the easiest time adapting to the family’s new life in Burnaby, in part because she was then the youngest (she now has two younger brothers).

She picked up English quickly – “languages for me are quite easy,” she says – and got involved in everything and anything she could. Her passions changed over the years, from getting into anime in Grade 5 and deciding to learn Japanese, to running track, writing poetry for school assemblies, doing slam poetry, writing stories, taking acting and modelling classes.

All through those years, Adhel says, she felt unsettled about herself. Wearing the label “refugee kid” means “you go through the school system underestimated or overestimated,” she says.

And there was a part of her that always felt like an outsider – something, her mother says, that remains true even after many years in Canada.

“Even if you say you are Canadian, they will still ask where are you from. You still look like this,” Amel says, pointing to the dark skin of her hand.

Adhel agrees.

“Growing up in B.C. I was always a minority,” she says. “In my day-to-day life there wasn’t a lot of people who looked like me. The only way I found a voice was through my artwork.”

Adhel says she always felt the pull between the two cultures that shaped her: her South Sudanese self and her Canadian self.

“There was a lot of confusion about which parts were me and which parts were given to me,” she says. “Stepping into myself was difficult.”

As she searched for herself, she realized her story was inescapably bound up in her mother’s.

Amel had never talked much about herself, or about the turmoil that had sent the family to Canada. But the curiosity of Amel’s inquisitive fourth child slowly changed that. Adhel would pick up snippets about her mother’s past from her aunts, and she’d badger her mother until she got bits and pieces of the story.

“Her, she liked asking a lot of questions,” Amel says, shooting a smile Adhel’s way. “I always used to say to her, you are going to be the one telling my story.”

AMEL’S STORY

Life wasn’t always hard. Growing up in South Sudan, she had a good life.

The tall woman with the gentle, lilting voice and the watchful dark eyes smiles as she talks about life with her family. Her dad was a teacher; her mom was a midwife. Amel was the firstborn of eight children. She went to school; she helped with the younger ones; she loved her parents.

She didn’t understand the political climate of South Sudan at the time. She’d hear her mom and grandmother talking about the war. Old people, like her grandmother, didn’t want the war to come.

It came.

The Second Sudanese Civil War broke out in 1983, as the central Sudanese government faced an uprising from the group that would become known as the Sudanese People’s Liberation Army. It would become one of the longest and bloodiest conflicts in world history, a 22-year war that would leave four million people displaced and two million dead from fighting, famine and disease.

It would also become notorious for its use of child soldiers.

Amel was 14 when she joined the SPLA after fighting in her town separated her from her family and sent her on the run with other children.

“If you are not a soldier by then, you will have a hard time,” she says, in explanation.

She headed off to training camp with what would become known as the women’s battalion. There, she met other girls her age, and some a little older, who looked out for each other and fought side by side. Going on thirty-five years later, Amel is matter-of-fact about the experience.

“It was dangerous. You can see the shooting. You can see the people die in front of you. You don’t know if you will survive or not.”

She saw friends die, and a teacher too. But somehow, she made it through four long years, trekking day after day en route to Ethiopia, where refugee camps awaited the child soldiers. “It was very difficult,” she says, in her soft voice. “It had to be walking, day and night, walking, walking, walking, from place to place.”

Her long journey took her next to Uganda, then onward to Kenya. By then, Amel had children, and she also had charge of her own younger siblings.

“My son, I had to tie him on my back and then walk,” she says, miming the action of wrapping her baby safely onto her back.

Somehow, she kept them all safe. She found work in Kenya, first as a preschool teacher and later as an interpreter for the United Nations. While the family lived in Nairobi, Amel’s two-bedroom home became known as a place of refuge for others in need – there were times, she laughs, when she had to wake people up just so she could get out the door in the morning, because so many people were sleeping on the floor.

Eventually, her UN contacts helped her find passage as a refugee.

At the time, she says, families weren’t choosing where they wanted to go. Several countries – Canada, the U.S., Australia, New Zealand, Norway – were coming to Kenya for refugees, and refugee families simply waited to be told where they would be heading.

Amel, her siblings and her children were granted refuge by Canada. She remembers the excitement of getting the news, and the profound sense of relief she felt.

“My children will get a good life,” she recalls thinking. “They will go to school. I’m not going to be worried about anything: no sickness, no killing.”

SILENT STRENGTH

As Amel’s story unfolded in bits and pieces for her daughter, Adhel came to understand and appreciate her mother’s strength and determination.

“My mom didn’t ever tell me that she’s strong; she just kind of quietly did it,” Adhel says, noting that strength transmitted itself to her children. “We were conditioned by her; she kind of forced us to be strong.”

Adhel laughs that growing up was “pretty much like a boot camp sometimes.” The kids were expected to get up and keep going, no matter what. She admits she was the family crier, the sensitive one, but everyone around her just kept telling her that she could do it.

“I had people always going, ‘Why are you stopping? Keep going, keep going,” she says. “Then finally I was like, ‘Yeah, I got this.’”

Now, she says, that determination is just built in to her nature.

“I don’t see anything that’s outside of my limitations. I always was encouraged to do whatever I wanted to do,” she says. “The limitations that exist are only within yourself. The worst that can happen is failure. My personal motto is just keep failing until you succeed.”

In 2015, Adhel decided to adopt a new name in keeping with her motto; she grew up as Lois, but, in discussion with Amel, changed it in honour of Amel’s father’s grandmother.

It’s an Arabic name meaning “the road that moves forward,” Adhel says.

“Even when you want to quit, your own name tells you to keep going,” she says with a smile.

A DIFFERENT PATH

It was a goal Amel could get behind.

“Always I tell her I want her to go to school,” Amel says. “I was willing to do that, but the war didn’t let me.”

Adhel admits her path has been “a little more avant garde” than Amel hoped. She chose to study fashion and found her way into modelling. She’s now based in Montreal, where she’s signed to the Dulcedo agency and works as a model. She’s eyeing the idea of going back to school after the documentary project is finished, to pursue a degree at Concordia or McGill.

Mother and daughter haven’t always seen eye to eye on her career direction so far – but then, they haven’t seen eye on eye on everything else, either. (Adhel notes, with a laugh, that they’ve been known to get into arguments about the meaning of words.)

“We are close; we fight, then we come together,” Amel sums it up with a smile.

Nonetheless, for Adhel, her mother’s voice is never far from her mind. Perhaps the single biggest piece of advice she lives by is Amel’s saying: “Be the head, not the tail.”

“If you’re a tail, people will drag you around, but if you’re a head, people will follow you,” Adhel explains.

Adhel is carrying that motto with her as she moves forward with her documentary project.

Right now she’s interviewing people for her filmmaking team, reading up on South Sudanese history and interviewing family members to learn everything she can before she starts filming.

As part of the STORYHIVE program, she gets assigned a mentor and has a chance to take part in creative meetings to help guide her project, and she hopes to start the actual shooting in a month or two. Her deadline to have the documentary finished is the summer of 2019.

Both mother and daughter are taking the documentary project as a chance to get to know each other on an entirely new level.

“It will be a way for her to know me,” Adhel says. “We are still getting to know each other a lot. I did a lot of growing outside my own house, and in my head. And I will get to know what she’s been through. It’s a long journey of discovering one another.”

But fundamentally, Adhel says, nothing will change how she feels about her mother – who was her “superhero” when she was little and who has become so again, but now in a genuine, adult way.

“There’s nothing that can really change how I see my mom,” Adhel says. “She always makes me proud, even the little things she does. Now everyone else can see who I saw. I want people to see the hero I had growing up.”