TORONTO — Merck Mercuriadis is holding a Canadian treasure in his hands.

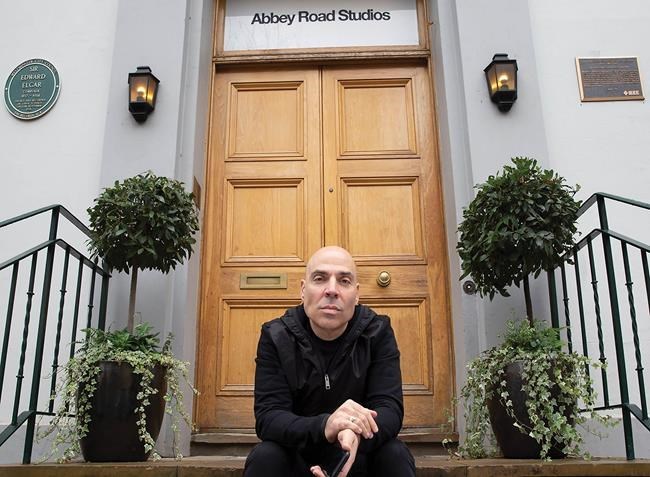

Deep into a conversation about the future of the music industry, the head of the Hipgnosis Songs Fund steps away from his webcam to pull a vinyl record from his shelf.

It’s a copy of Joni Mitchell’s latest archival album released last year.

And even if Mercuriadis won’t say it aloud, it’s not hard to imagine he feels the Alberta native’s "sublime" work is one of the jewels of Canadiana missing from his company's crown.

“It's so life-affirming that someone could be that amazing, that hot, and the words and voice that incredible,” he says of Mitchell's influence while clutching the album.

Mercuriadis, who grew up in Middleton, N.S., knows the value of a legendary song. In his career, he rose from a teenager cutting his teeth at a Canadian record label to helping manage the likes of Elton John, Beyonce and Mary J. Blige.

Over the past three years, he's forged a more public name for himself as the founder of Hipgnosis, which has been on a buying spree throughout the record business. The company is paying billions of dollars for full or partial ownership rights to thousands upon thousands of iconic songs, including the work of many Canadians.

In early January, Mercuriadis secured a 50 per cent stake in the rights for 1,180 of Neil Young’s songs, including "Heart of Gold" and "Harvest Moon."

A few weeks later, he purchased the royalty rights owned by Winnipeg-born producer Bob Rock on some of Michael Buble's Christmas hits and Metallica's "Enter Sandman."

Mercuriadis believes there’s untapped potential in many of Canada’s most classic tunes.

"There’s Canadian music that is amongst the most important music in the world," he said, pointing to Young’s songbook, Robbie Robertson and Rush as examples.

"These people are making music the rest of the world loves, respects, and that's a part of the fabric of our society."

He's not alone in seeing the value in buying up massive catalogues.

Rights acquisitions have become a hot commodity in the pandemic as the global concert industry remains at a standstill.

That's led a few smaller Canadian labels to explore their options, and in some cases sell their assets.

Linus Entertainment, home to Fred Penner and Gordon Lightfoot, made a number of acquisitions in recent months, including taking ownership of independent folk label Borealis Records.

And Quebecor Sports and Entertainment announced on Wednesday it was buying the French-Canadian label Audiogram, home to Bran Van 3000 and Pierre Lapointe.

Songwriters with established names have seen Hipgnosis and others show up at their doorstep with significant lump-sum offers in exchange for ownership of their royalty stakes.

In theory, these companies see a growing flow of income from streaming music platforms, placement in TV shows and money earned through covers by other musicians.

Hipgnosis and other investors behind marquee acquisitions also point to a new generation of revenue streams flowing from less obvious places: exercise bike company Peloton, for instance, pays royalties on music used in its online classes, and TikTok videos can elevate dusty old hits like Fleetwood Mac’s “Dreams” back onto the charts almost overnight.

Canadian music manager Bruce Allen, who helped negotiate the sale of Rock’s songs to Hipgnosis, says for many established performers, shedding their past catalogue makes sense. It gives them a retirement fund to rely on and prevents infighting between relatives when the ownership rights fall to them after the musician dies.

"Look at the mess that we have with Prince or Tom Petty, Michael Jackson, James Brown, Aretha Franklin. It just goes on and on with estates battling over the spoils of the poor fellow who died," said Allen.

"If ... a guy wants to pay me 23 times earnings and I'm 70 years old, I would say, 'You know what, that's not a bad idea.'"

But it's not just estate planning that drives musicians to part with their ownership rights.

Toronto songwriter Dan Hill says he became tired of chasing down companies who were using versions of his 1977 ballad “Sometimes When We Touch” without his permission.

The song had shown up in commercials that aired outside North America, and when Hill heard about it, the offenders refused to pay up. The next step was calling his lawyers to threaten legal action.

"I don't want to spend eight hours a day doing this anymore," he remembers thinking.

"I'd rather just spend time writing songs."

Three years ago, Hill sold his ownership stake in all of his past work to Anthem Entertainment for "well over a million" dollars. The Canadian music rights manager, formerly known as Ole, is also home to Rush's catalogue.

Not everyone is convinced parting ways is the right choice, however.

Bryan Adams has rebuffed offers for his valuable catalogue of 1980s and 1990s hits, while "Sugar, Sugar" co-writer Andy Kim says he’s not interested in handing over his life's work in exchange for a bag of cash.

One of his biggest concerns is what happens if a buyer he trusts winds up in a financial bind.

"All companies can go bankrupt, so what happens (then)?" Kim says.

"My instinct has always been no… What's going on today, I think it's great for those who feel (the need to) cash in now. But in my will, I’ll give (the rights) away to people that I really like and love."

Those sentiments are familiar to Mercuriadis, who's sat across from some of the biggest names in the industry to make his case.

Young was reluctant to relinquish even a fraction of his power over "Rockin' in the Free World" and his other classics, concerned they'd wind up in advertisements for automobiles or fast food joints.

Mercuriadis says he promised the folk singer an exceptional relationship where he'd personally oversee his portfolio of songs.

The rest of Hipgnosis's nearly 80-person staff takes responsibility for small bundles of songs assigned to them. Their objective is to maximize the overall value by placing the songs in the right places while making sure the songs aren't misused or abused in a way that would taint their legacy.

"Sometimes that's as simple as making sure the song is on the right playlist," he says.

"So if someone's got a playlist and it's got Bon Iver on it, there should be a Neil Young song... if it's got Frank Ocean on it, there should be a Neil Young song.

"Or it can be as detailed as getting in front of Martin Scorsese and making sure that for the movie he's making that he's either thinking about songs he hasn't thought about before or being reminded of songs that are important to him."

It's this defining characteristic that Mercuriadis says makes his company stand out from competitors.

"If we're ever in doubt, we refer to the songwriter," Mercuriadis says.

"The acquisition is the beginning of our relationship."

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Feb. 10, 2021.

David Friend, The Canadian Press