When it comes to students graduating from high school, the Burnaby school district is ahead of the curve.

For well over a decade, the district has been ahead of the provincial average – by as much as seven per cent – when it comes to six-year completion rates (the percentage of students who graduate with a Dogwood or adult diploma within six years of the first time they start Grade 8).

But for Indigenous students, who make up about three per cent of the student population, things have been very different.

For as long as Burnaby’s overall grad rate has been above the provincial average, its grad rate for Aboriginal students has been well below it – and even below the average for all Aboriginal students in the province.

Until last year, that is.

In 2017/18, nearly 71 per cent of Indigenous students in Burnaby graduated within six years of starting Grade 8.

That’s a 22 per cent jump from the year before and nearly one per cent higher than the provincial average for Aboriginal kids.

While that means nearly a third of Burnaby’s Indigenous students still aren’t graduating, it’s a long way from nine years ago when more than two thirds dropped out before finishing Grade 12.

‘System-wide approach’

“It’s been a long road, and by no means do we believe that reaching a 70 per cent graduation rate means we’ve figured out how best to support each individual Indigenous student in our district, but I think it’s showing that we’re starting to head down the right path,” district principal of Indigenous education Brandon Curr told the NOW.

One thing that contributed to the big jump in rates last year was what Curr called “a big, helpful piece of useable data” from the ministry of education.

For the first time in his memory, the ministry sent the district a list of names of Indigenous students in their sixth year since Grade 8 who hadn’t graduated but whose last school contact had been in Burnaby.

“There were a number of students last year, who otherwise would have counted as a non-grad in our district, where we were able to reach out to them and connect them with either adult education or an alternative learning environment or connect them back to their home schools to finish the few courses that they had left uncompleted,” Curr said.

The goal however, is to move beyond “playing catch-up in year six,” according to Curr.

Toward that end, he said, the district has been using what he calls a “system-wide approach” that includes professional development for all staff to deepen their understanding of Indigenous culture, perspectives and worldviews.

The district’s goal – supported by the province’s new curriculum launched in 2015 – is to weave Indigenous culture into all school subjects and activities, not just include them as “one-offs” and “add-ons.”

Take math. A “learning team” comprised of math teachers and the district’s Indigenous education team is currently working on ways to incorporate “Indigenous pedagogy into mathematics,” according to Curr.

Student engagement

The district has also worked on engaging Indigenous students in “culturally relevant learning activities.”

That’s made a difference to students like Moscrop Secondary Grade 12 student Jaisen Axworthy, whose family is originally from First Nations near Chase and Mt. Currie.

He remembers his elementary school, Inman Elementary, hosting Aboriginal circles featuring Indigenous speakers and hands-on activities, like making dreamcatchers or drums.

“It was nice because we got to learn a thing or two,” he said. “For me it was nice because it wasn’t really talked about much growing up.”

Axworthy, who is on track to graduate this year, wants to get into BCIT’s Trades Discovery program next year.

Alpha Secondary Grade 12 student Nina Mawji-Sparvier also didn’t know much about her Indigenous heritage until about Grade 7, when Aboriginal circles at her Coquitlam middle school sparked her interest.

“It was about the smudge,” she said of the First Nations ceremony that involves burning sacred herbs for spiritual cleansing or blessing. “They would always smudge us at the beginning and the end, and I loved it. I loved the smell; it made me calm.”

Those activities at school sparked conversations with her mother, who had become disconnected with her Plains Cree family in Saskatchewan after her father, a residential school survivor, left her mother.

‘Safe place’

In high school in Coquitlam, Mawji-Sparvier said there was little support for her as an Indigenous student, but that changed when she came to Alpha, where there is a dedicated resource room staffed with a youth engagement worker.

“It’s just such a safe place from school and even from home for some students, which I do think is very important,” Mawji-Sparvier said.

When asked to name the most important thing the district could do to help Aboriginal students succeed, Mawji-Sparvier is emphatic: Every high school should have a dedicated room for Indigenous students staffed by a full-time support worker.

Currently, youth engagement worker Lorelei Lyons is at Alpha only two days a week.

“A lot can happen those other days for any Indigenous student,” Mawji-Sparvier said. “I think this should definitely be full time, just daily check-ins, monitoring the students. It’s pushing them. A lot of students don’t have that push at home and the support and positive role model.”

Mawji-Sparvier is also on track to graduate this year and plans to study human and social sciences at Native Education College and become a criminal defence lawyer one day.

Student voices

To get a deeper understanding of the day-to-day experiences of its Indigenous students, the district is hosting an Indigenous Student Voice Forum in February.

It’s part of a larger provincial initiative called the Indigenous Education Equity Scan, designed to help districts remove obstacles and make schools more truly inclusive for Indigenous students.

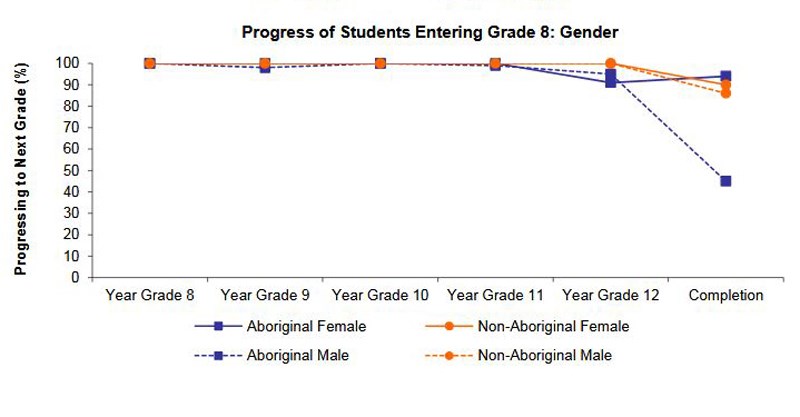

One issue the district will be looking to shed light on is the big divide between the grad rates of Indigenous girls versus boys.

While the rate for girls jumped to 94 per cent last year (four per cent higher than the average for all girls in the district and 21 per cent higher than all Aboriginal girls in the province), the rate for boys stayed flat at 45 per cent (41 per cent below the average for all boys in the district and 21 per cent below the provincial average for Aboriginal boys).

Unfortunately, it’s not a new trend, according to Curr.

“Our boys continue to experience challenges within our schools,” he said. “That continues to be an area that we need to pay attention to.”