In an average year, more than 7,000 residents in long-term care die.

In an average year, their loved ones get a chance to hold their hands or brush their hair, to talk to them or just be with them during their last months and weeks.

This has not been an average year.

COVID-19 has taken the lives of many seniors at B.C. care homes since March, but it has also robbed many others of some of their last moments with family and friends.

In Part 1 of a two-part series on the pandemic’s impact on seniors’ last days in long-term care homes, here are the stories of two such families in Burnaby.

◆◆◆

‘Not this way’

The last time Maria Banath saw her 91-year-old mother alive, Banath was swathed in a surgical gown, face shield, gloves and mask.

Her mother had been infected with COVID-19 at the New Vista Care Home, but that’s not what killed her, according to Banath.

Anna Patano, a longtime North Burnaby resident who had moved to Canada from Italy in 1964, had stopped eating on Aug. 15 and begun refusing all fluids starting Aug. 26, before she finally died on Sept. 13, her daughter said.

Patano’s contact with loved ones during her last few months was cut off for long periods at a time because of lockdowns related to two coronavirus outbreaks at her care home.

COVID-19 had plagued New Vista since a staff member there tested positive for the deadly virus in April.

That initial outbreak was declared over on June 8, but the home was hit by a second outbreak when another staff member tested positive on Aug. 8.

In all, 12 deaths at New Vista have been linked to the outbreaks, one death associated with the first outbreak and 11 with the second, according to the Fraser Health Authority.

Banath said her mother had spent 75 days in total lockdown – 52 days during the first outbreak and 23 days during the second – before she died.

‘A really good place’

Despite her age, Banath said her mother was “full of life” with “lots of spirit in her” before the outbreaks hit the centre.

She took some time to settle in, but New Vista was “a really good place” for Patano, Banath said, since dementia-related behavioural issues made it impossible for her to care for her mother on her own.

“Before COVID, I was there every day, faithfully, because I did her care,” Banath said. “I was there all the time, every day, not a day missing.”

That ended abruptly for 52 days when the care home banned all visitors on April 30 in response to the first outbreak.

Banath’s only contact with her mother during that time was limited to phone calls and one weekly FaceTime call arranged by staff at the home.

New Vista told the NOW in May it had purchased “a whole bunch of iPads” and that staff was facilitating FaceTime calls between residents and their loved ones during the lockdown.

But only two iPads have been made available to about 236 residents for FaceTime calls, according to emails exchanged between Banath at the care home.

New Vista purchased 12 iPads, according to the emails, but there is no Wi-Fi in the building, and data was purchased for only two of the devices.

Banath’s first FaceTime call with her mother on May 8 was “not much of a visit,” she said. Patano was “very groggy,” and staff had to move on to other residents.

When the first lockdown finally ended on June 22, Banath was allowed to visit her for an hour-and-a-half every second day wearing full PPE.

“In good weather after supper I was able to take her out in the garden area within the building as she loved outdoors,” Banath said.

But that reprieve was short-lived.

‘She was totally out of it’

Less than two months later, all visits were banned again when a second outbreak hit.

Patano would be dead before it was over, after she had stopped eating for nearly a month, according to Banath.

She said her mother didn’t want to take the antipsychotic drug loxapine, and, when she refused it, staff put it in her food and drink.

“I think that’s part of it,” Banath said, “and then not seeing a familiar face around didn’t help.”

Patano said her mother, who was in a unit for residents with behavioural issues, was supposed to be given loxapine “as needed,” but neither Patano nor Banath liked the effects of the drug.

“It knocked her out for three days,” Banath said. “When she did wake up, she had no energy. She was totally out of it.”

After seeing those effects, Banath said she had asked New Vista to call her instead of administering the drug when her mother was agitated.

Antipsychotic drugs like loxapine are used to treat behavioural and psychological symptoms in patients with dementia, but their overuse in long-term care facilities has long been a concern, according B.C.’s seniors advocate, Isobel Mackenzie.

She said the province had succeeded in bringing down the use of antipsychotics at care homes over the last five years, but those numbers surged when COVID-19 hit.

“In the last six months, we’ve almost given up the gains of the last five years,” she said. “This is not a trend we want to see.”

By the time Banath was allowed to see her mother again during the second outbreak at New Vista, the visits were considered “palliative,” she said.

Because Patano was COVID-positive, she was in isolation, and her daughter had to make her half-hour-a-day visits in full PPE until Patano’s body finally gave up 13 days later.

“Mom eventually would have passed, yes, and so will I, but not this way,” Banath said. “Not this way. It should have never happened this way.”

The Burnaby NOW contacted New Vista for this story. New Vista Society CEO Darin Froese declined to be interviewed or provide a comment.

◆◆◆

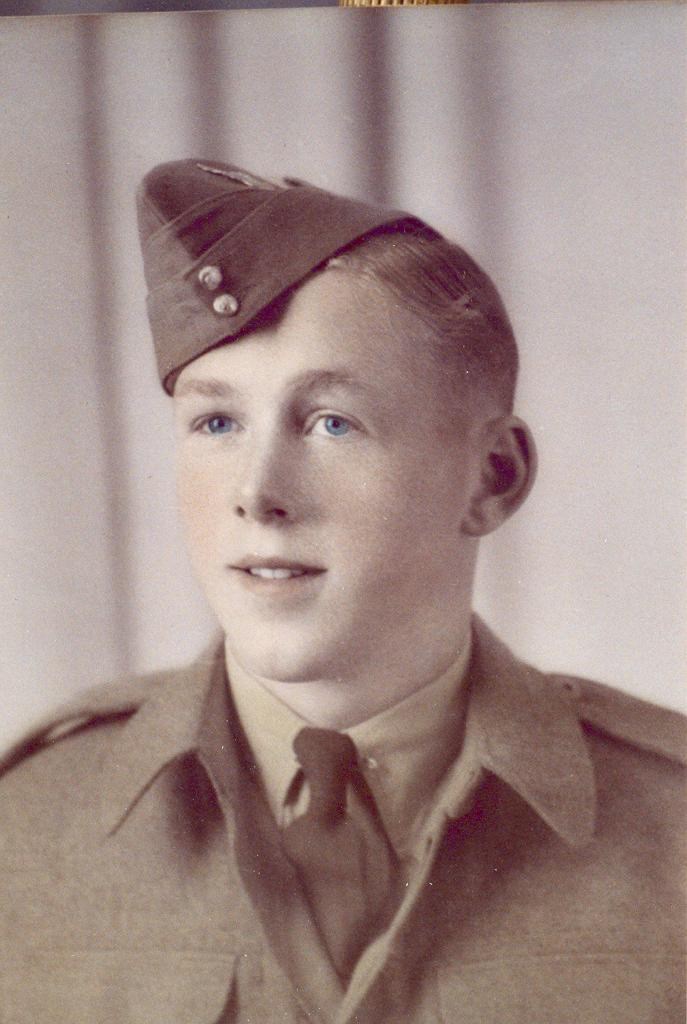

‘I had no idea how he was doing’

When Robert Pitman died on May 26, he wasn’t alone. His son was in the room with him, and his daughter, Sandy Jones, was in another room nearby. But his two months of experience with the pandemic were likely characterized by loneliness and confusion, having been unable to see or speak to his family for well over a month as his health deteriorated.

Before the pandemic, Jones says she would visit her father five times a week.

“I really felt badly for anybody who didn’t have that ability to have a loved one come in and check in with them more than once a week or once a month,” Jones says. “I was the eyes and ears for my dad. I was there often enough to see when things went awry.”

When his room was messy, for instance, she often stepped up to tidy it, she says, and she noticed twice when his watch was misplaced.

After the pandemic struck, however, Jones didn’t get to see her father, a resident of the George Derby Centre, for well over a month, nor did she get to speak to him on the phone.

“He had dementia and couldn’t quite figure out how to place the phone, and it would slide from his ear, and he’d sort of not realize it, that kind of thing,” Jones says.

Although the centre was facilitating FaceTime calls between families and residents, that service was advertised on Facebook and on its website – two sites Jones says she rarely visits. She called regularly and got brief updates from staff, but otherwise she didn’t see her father until May.

“I had no idea how he was doing, how his health was progressing,” she says.

A people person

When she describes Pitman, Jones tells of his love of people, his smile and the jokes he would tell to see that grin reflected back at him.

But with the pandemic came new safety protocols, and in care homes, masks are now mandatory for staff.

“I was just trying to imagine the fact that he’s sitting there at George Derby seeing only eyes. My dad was very much a people person,” Jones says. “He couldn’t see a smile behind a mask, even though, perhaps, they were treating him lovely.”

Jones believes the sudden isolation played a role in Pitman’s turn for the worse. The downward spiral was visible by the time she was finally able to see her father on a FaceTime call – he was thin from refusing to eat, confused and uncharacteristically angry.

“My dad was always a happy person,” she says. “He was very upset, and I was upset to see him in that state.”

Outbreak protocol

Families became particularly concerned when an outbreak struck the care centre in August – ultimately, seven people contracted the virus, including three residents and four staff, and one resident died.

During the outbreak, window visits were ruled out by the care centre when in-person visits were banned. According to executive director Ava Turner, the window visit ban was because family members tend to try to open the windows.

“If you come around here sometimes, you’ll see families trying to get their heads into the windows, into the room,” Turner says. “So unless I’m out there, I have security all the way around, that is particularly what happened. I don’t know if family members have COVID out there or they don’t.”

Even more concerning for some family members was the care home putting on hold the staff-facilitated phone or video calls between residents and their family members. Turner is quick to note the facility implemented the calls before anyone asked for the service, but when the outbreak struck, they were faced with staffing issues.

“Absolutely, it was all hands on deck to make sure that the service happens in each resident’s room, and that the residents who needed to be supported with feeding, that someone would be there supporting them with feeding,” Turner says. “That meant the team who was supporting the calls, I needed to utilize them more effectively and efficiently, and that meant they needed to support the residents who needed to be fed.”

‘That’s how it ended’

After seeing on their FaceTime call how thin Pitman had gotten, Jones says she asked to see his weight measurements, which only confirmed the significant weight loss.

“I was very upset at that, and I requested a visit. I insisted that they allow me to get in to see dad so that I could coax him to eat,” she says.

But when she was allowed to visit Pitman, she says he only gagged when food was brought close to his mouth. That was her last 15 minutes with her father until he was identified as “actively dying,” Jones says. And Pitman, himself, seemed to have sensed that the end was near.

“The only thing that he said sort of legibly was ‘Take care of yourself, Sandra,’” Jones says of their lunch meeting.

Jones and her brother were able to visit Pitman in the hours before his death, but even then, she says, she was expected to wear a mask.

“I simply took my mask off so he would know me, because I knew these were his final hours,” she says. “When dad passed, (my brother) was actually with dad in the room, and I was outside, along with my sister-in-law and the grandchildren. So that’s how it ended for my dad.”

A widespread issue

The families of Anna Patano and Robert Pitman are not alone. The isolation of seniors in long-term care during the COVID-19 pandemic has raised concerns provincewide. Next week, the seniors advocate will release the results of a survey launched at the end of August to probe the impact of visitor restrictions on seniors in care and their loved ones.

For Part 2 of our series – available here – we talk to the seniors advocate and to an SFU professor who says the “silver lining” of COVID may be that it has shone a light on problems in senior care that existed before the pandemic.

Follow the authors at @dustinrgodfrey and @CorNaylor

Email [email protected] and [email protected]

◆◆◆◆◆◆