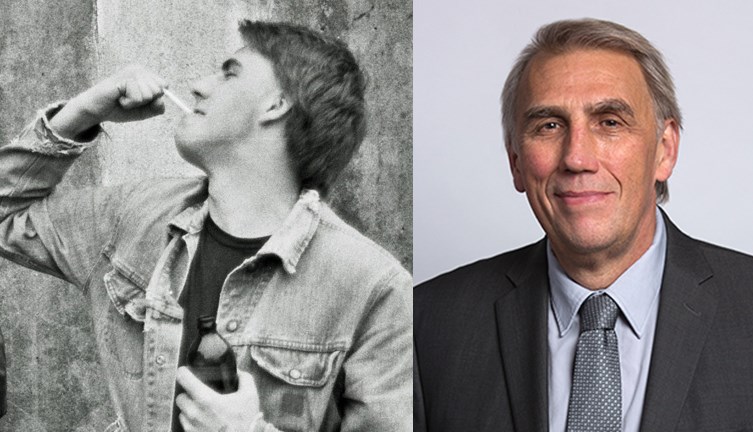

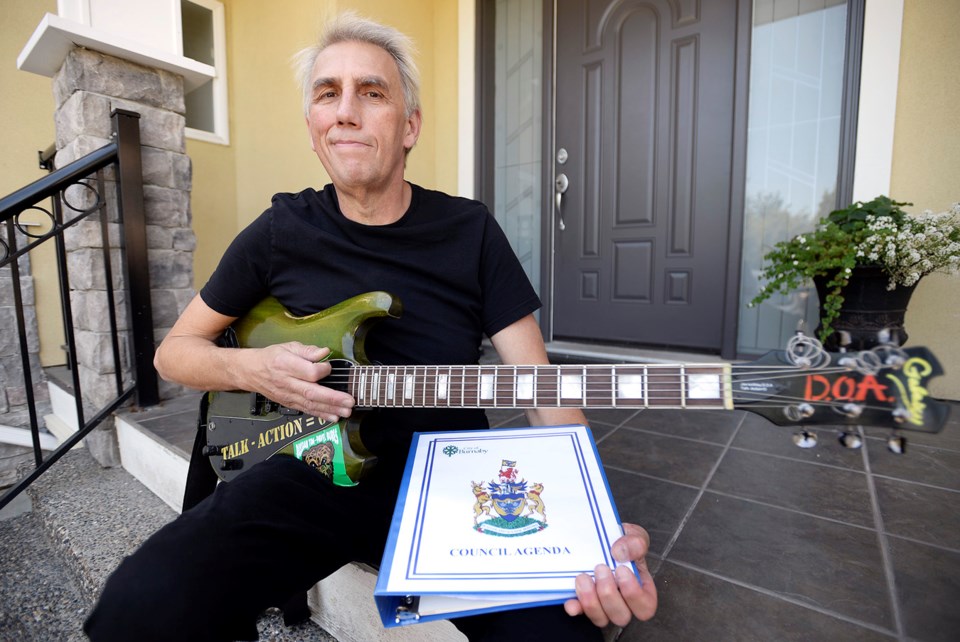

Joey Shithead has been possessed. A politician has taken control of the punk rocker, stuffed him in a suit and given him a new name: Councillor Joe Keithley.

The man who sang “Smash the State” is now a cog in the political machine he spent decades raging against. The guy who pilloried developers for their heartless greed now calls them “nice people.” And the punk who penned anti-police anthems now boasts of a “good relationship” with the local detachment.

What the hell happened?

⚫ ⚫ ⚫

A few dozen people huddled around a laptop in Joe Keithley’s kitchen to watch results roll in for the 2018 municipal election. He was in ninth place most of the night – one spot short of a seat on council.

It was familiar territory. Another election loss was nothing new. He could keep fighting the system from the outside.

Then his daughter refreshed the page. Suddenly, Keithley was in the top eight.

“I was like, ‘Oh… really?’ ” he recalls months later.

By the end of the night, he held the eighth and final spot. After decades of playing the outside agitator, Keithley was suddenly on the inside.

The punk cracked a beer and thought to himself, “OK, I’m in this now. I’ve got nobody to blame but myself.”

⚫ ⚫ ⚫

The music came first. At age 11, Joe Keithley was transfixed by a drummer playing in a jazz band at his sister’s wedding. He was soon banging on a kit of his own, much to his father’s chagrin. (“He was super square. My dad was completely right wing.”)

Next came the guitar. And some of his Burnaby North Secondary classmates became bandmates.

Then came the politics.

It was the early ’70s, the Vietnam War was raging, and the Americans about to test nuclear weapons off Alaska’s Amchitka Island. Keithley, then 16, marched out of school with 300 fellow students, joining a protest organized by Greenpeace.

“The principal tried to block us in the driveway,” Keithley recalls. “One grown man against all these kids.”

They marched to Alpha, Van Tech and Britannia, picking up more kids at each high school en route to the main protest in downtown Vancouver. Along the way, Keithley’s bandmate, Ken "Dimwit" Montgomery, thumped a homemade bass drum, keeping the young rabble rousers on pace.

Ever since, music and activism have been fused at the centre of Keithley’s life in the combination of brazen politics and brash sounds known as punk rock. The teens loved the new genre. It was the perfect antidote to the “mundane” music they heard on the radio – bands like Led Zeppelin and Deep Purple, who were “just about the rock” with no greater message, Keithley recalls.

Punk was different.

“You could express yourself musically and lyrically pretty well any way you wanted and be outrageous … the way rock was supposed to be before it was co-opted by Elvis Presley.”

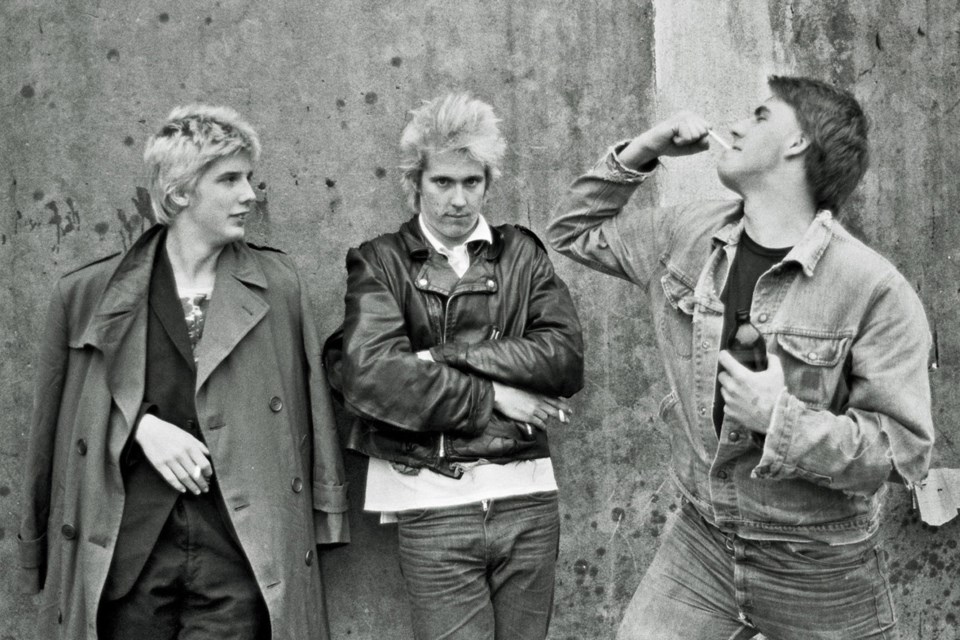

So the Burnaby boys formed a band – The Skulls. Later, it became D.O.A.

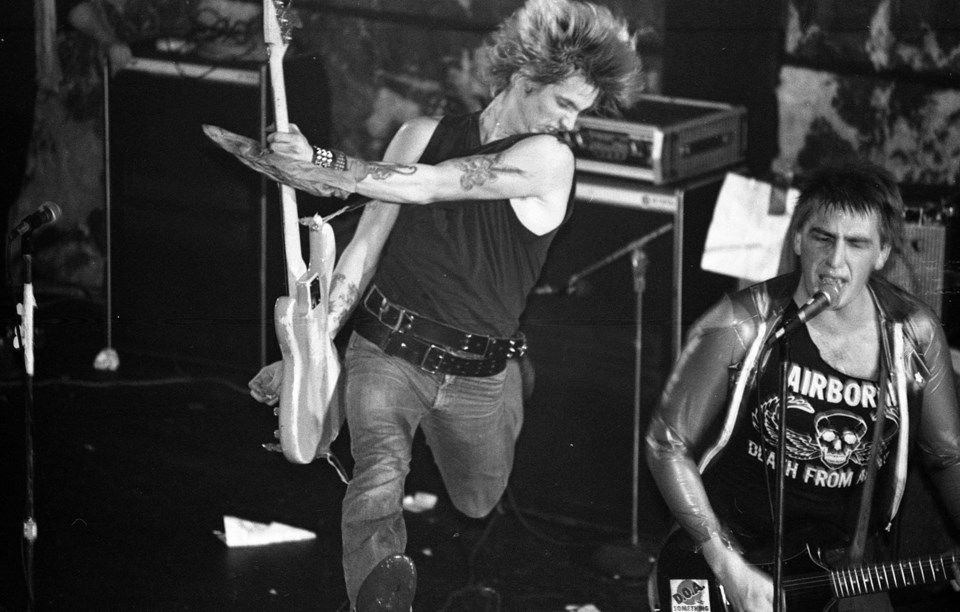

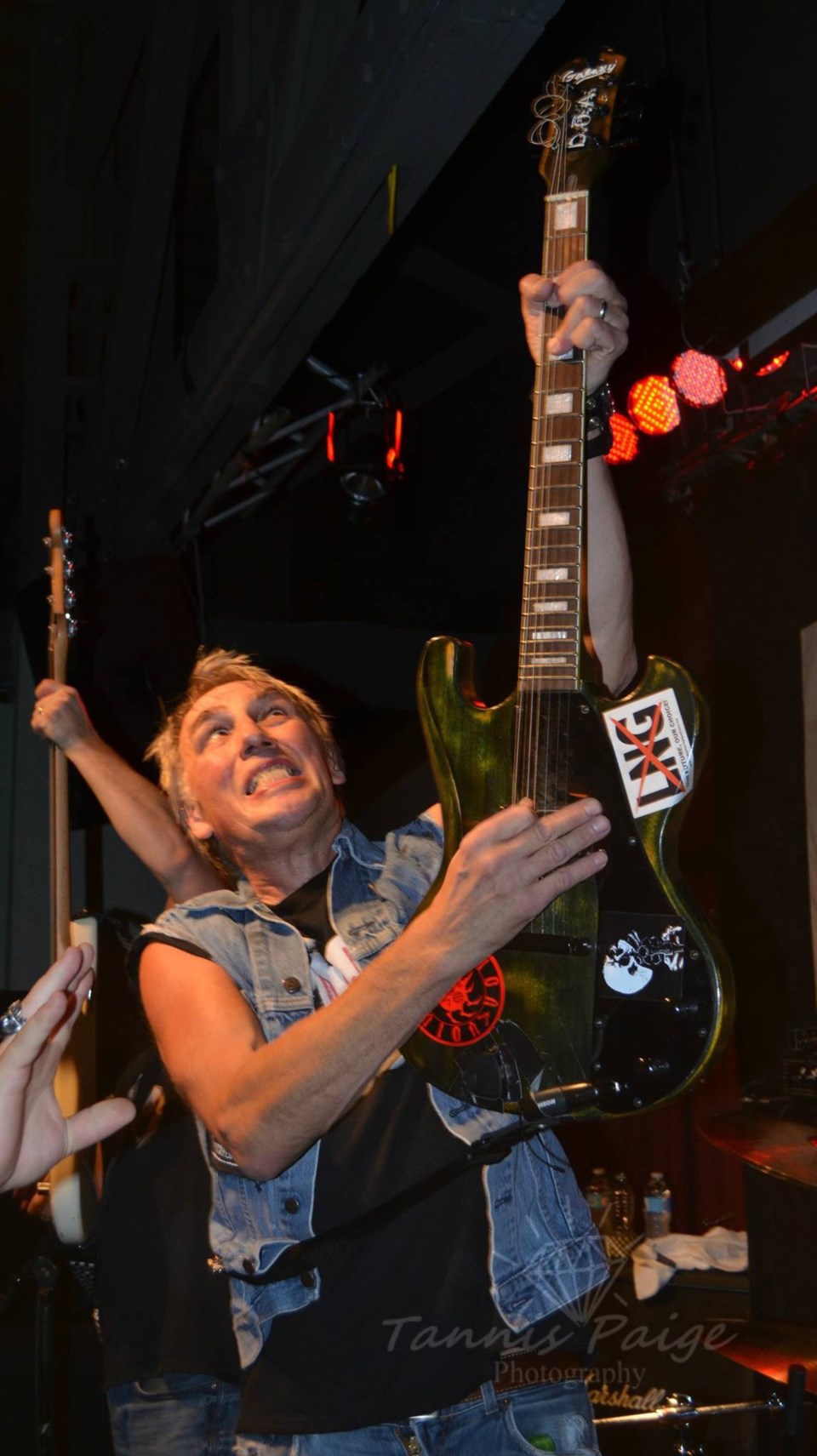

In the four decades since, D.O.A. has released 17 studio albums, toured the world many times over and has cemented itself as one of the world’s most famous, outspoken and long-lasting punk groups. The band has been through many lineup changes, with only one constant: Keithley, known onstage as Joey Shithead, on guitar and vocals.

Dale Wiese, owner of Vancouver record store Noize to Go, first saw D.O.A play a (literally) underground club in Edmonton in the ’70s.

“Right from the first note, I’d never seen anything so powerful from three people. The sheer power of the delivery and ferocity of it – and yet, it was tuneful and the songs were well-structured,” he recalls. “This idea of trying to make a difference through music wasn’t exactly new; they just added a lot of amplification and volume.”

All these years later, D.O.A.’s fierce music is still ringing in the ears of punks young and old. Wiese says his best seller this summer was a new compilation of D.O.A.’s early music.

⚫ ⚫ ⚫

Keithley estimates at least half – maybe two-thirds – of the dozens of songs he’s written are explicitly political.

He targets violent cops in “The Enemy.”

In “Slumlord,” he describes a “neighbourhood bully … Waving his finger like a pistol / Flapping his jaw like Adolf Hitler.”

“Class War” leaves nothing to the imagination: “I want a war between the rich and the poor.”

And the message is even more blunt in 1981’s “Smash the State”: “Kill Pierre Trudeau … Kill Ronnie Regan … Kill Margaret Thatcher … Kill them all.”

But Keithley has done more than bellow rabid polemics from stage and studio. An equation emblazoned on thousands of black T-shirts worn around the world serves as the band’s slogan: “Talk - Action = 0.”

D.O.A. has campaigned against pulp and paper mills polluting Howe Sound. They played Rock against Radiation in Vancouver and Rock Against Racism in Chicago.

To draw attention to planned logging of old-growth forest, D.O.A travelled to the Stein Valley in 1986. Local loggers tried to shut the benefit concert down. They didn’t take kindly to the punks coming in from the city to tell them what (not) to do.

“You don’t show up to a chainsaw fight armed with a guitar,” Keithley laughs more than 30 years later as he sits at his kitchen table, aging dogs lounging at his feet.

When B.C. Premier Bill Bennett cut aid to women’s groups and curtailed workers’ bargaining rights, some in the province called for widespread labour action. D.O.A. agreed and recorded a new song, “General Strike,” in solidarity.

In the early ’80s, a friend of Keithley’s took the “action” maxim much further. Gerry Hannah, the former frontman of rival punk group The Subhumans, was a member of the Squamish 5, a guerilla group found guilty in a series of politically motivated bombings.

When the group was arrested, D.O.A. played a benefit concert fundraising for their legal defence. Keithley said he was convinced the Squamish 5 wouldn’t get a fair trial and wanted to help, despite vehemently disagreeing with their tactics.

“One of the reasons Canada is one of the greatest places in the world is that there’s a level of civil discourse where we don’t settle things by killing people, hijacking, kidnapping, blowing up people. We always have to keep that in mind, or we go down a really bad slope,” Keithley says.

⚫ ⚫ ⚫

Keithley made his first foray into politics with the B.C. Greens in 1996. The party had six guiding principles but no platform. They supplied him with three cloth signs emblazoned with sunflowers – and nothing else. He printed his own flyers, bribed his young kids with candy to distribute them and called it a campaign. He came in fourth, pulling less than two per cent of the vote in Burnaby Willingdon.

The next year, he teamed up with neighbours who were trying to stop the sale of public land to Kodak. The Community Environment Responsibility party candidates “got shelled” in that municipal election, finishing at the bottom of the pack.

In 2001, the provincial Greens had a more fulsome platform, a new leader in Adriane Carr, more signs and more pamphlets. Keithley ran again, earning a respectable third-place finish, with nearly 15 per cent of the vote.

After a few years away from politics, he decided to run for the NDP in 2012 but failed to win the nomination in Coquitlam.

He was back with the Greens for a 2016 byelection and the general provincial election in 2017 – a breakthrough year that saw three Green MLAs elected but still left Keithley on the outside, looking in.

That finally changed in 2018.

As the municipal election neared, Keithley helped assemble a municipal Green party. They first planned to run the punk rocker as a mayoral candidate to oust longtime incumbent Derek Corrigan, but Keithley changed course, endorsing independent Mike Hurley for mayor, and sought a council seat instead.

By the end of the night, Hurley had won the mayor’s chair and Keithley the eighth and final councillor’s chair. The two would soon sit alongside seven incumbent councillors they had spent much of the campaign criticizing.

As he sipped his celebratory beer on election night (Oct. 20, 2018) Keithley thought of the road ahead.

“I’m elected now, so I’m going to make the best of it,” he thought.

⚫ ⚫ ⚫

In the beginning, the newly elected politician was relatively quiet at public meetings, taking time to listen and learn how to work within the system.

Keithley admits to encountering a “steep curve” as he tried to keep up with councillors with decades more experience. He eventually began piping up – something he’d been doing his whole life – but the language he used in council chambers was a little more delicate than his lyrics.

When council approved a new bike lane, he said he looked forward to riding it with his grandson. He spoke against a proposed liquor store, worried about the impact it would have on traffic. And he has pushed for the city to accelerate construction of new sidewalks, an initiative he feels is of particular importance to seniors.

Mere weeks after returning from D.O.A.’s latest European tour, he brought forward a motion asking staff to study the “advisability and feasibility” of banning the advertisement of e-cigarettes on city-owned structures, calling the bus-shelter billboards “a really bad influence on our youth.”

As a member of the mayor’s housing task force, he sat alongside the very developers he long criticized. Rather than call them “neighbourhood bullies,” he now says, “They were nice people, but their idea would be that we have no taxes and [the city allows them to] just build as many buildings as they can.”

Shithead wrote at least four “anti-police” songs, including “Royal Police,” in which he belts “they're bloody fools ... with their stupid rules ... kick'em out ... beat'em about.” But Keithley now says, “I don’t know if I’m friends, but I have a good relationship with the chief superintendent and the different members of the RCMP, and I’ve gotten along with them really good.”

“Policing today in Canada is a lot more gentle and kind than it was 30, 40 years ago. The police thing is ‘To protect and serve,’ and if they don’t, there should be an inquiry into it,” he says.

“Not to couch words too much.”

How can a man who wrote about killing Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau in “Smash the State,” reconcile that message with his new, tamer rhetoric? “I’m not the same man I was at 20 when I wrote that,” explains the now-63-year-old with a wife of 33 years, three kids, a grandchild and a silver minivan parked in a quiet suburban cul de sac.

The song was never intended to be taken literally, he says. It was merely a punk’s way of condemning the actions of politicians he didn’t like. When he sings the song now, modern leaders are targeted instead, including Donald Trump and Vladimir Putin.

Sometimes he’s asked “Where’s your guitar? Where’s your mohawk?” by seemingly disappointed fans. “The ones that would expect the sort of caricature punk rocker to be there … that’s not happening.”

⚫ ⚫ ⚫

The gap between Keithley’s songs and his statements as a politician should not be read as contradictory or disingenuous, says Catherine Corrigall-Brown, a University of British Columbia sociologist who studies activism.

“A song is art, and art often pushes messages to the extreme,” she says.

“If you said ‘Inequality in society has increased over time, and there are 15 reasons why,’ that’s already quite boring, right? You break out with ‘Down with the state!’ that’s much more interesting.”

“The cost of that is the more nuanced part of your message gets lost.”

According to Corrigall-Brown, Keithley’s trajectory is quite common: activists often change tactics later in life while remaining committed to their cause. Rather than marching in the streets, true believers often turn to law, social work or – sometimes – politics.

People don’t really change, she says.

“We have this stereotype that people are super radical when they’re young, and then they become really conservative when they’re old – they kind of grow out of their radicalness. It actually turns out that, for the vast majority of people, your political attitudes when you’re 20 are pretty similar to your political attitudes when you’re 60.”

⚫ ⚫ ⚫

Keithley is adjusting to the slow pace of change at city hall, where nothing happens overnight. Reports, plans, consultation and studies take months before council can take definitive action.

“As an activist and as a would-be politician before I got elected, I thought, ‘Damn, why doesn’t council do stuff faster?’ And people would say to me, ‘Joe, you can’t fight city hall.’

“And I always hated that expression and thought, ‘Of course you can fight city hall.’ ”

But now he’s on the other side.

“The activists would have us build 50,000 housing units and have them operating in six months. It’s not going to happen. You can’t build stuff that fast. You can’t set aside the land that quickly.

“Now I realize there’s a lot of competing interests.”

Hurley says Keithley has been “very adamant” on housing and other issues close to his heart since being elected – just not “in a radical way that he’s sung about in his songs.

“He’s realized that probably that smashmouth approach doesn’t work.”

The first time Coun. Nick Volkow saw his new colleague, he was thrashing onstage at Vancouver concert. “Those guys had a lot of high energy,” he recalls. But Volkow says he’s not too surprised to see a different character sitting beside him at council meetings.

Keithley has “taken to the job really well,” Volkow says, pointing to his laser-focus on social justice and environmental issues.

“You know what? I’m going to use the term – he’s a legitimate class warrior.”

Wiese, who has known Keithley for decades, attributes Keithley’s new approach to his years of world travel, saying “He’s become something of a diplomat.”

Keithley, meanwhile, sees it in simpler terms. “I kind of was an unofficial politician for 40 years, and I guess on October 20th I became an official politician.”