B.C.’s Strait of Georgia could become a dead zone for sea snails as warming seas upend the region’s ecological balance and usher in the emergence of “novel ecosystems,” a recent study has found.

The study, published this fall in the journal Ecology, tested how the intertidal dogwhelk snails would handle warming sea water along the Central Coast and the Strait of Georgia to the south.

Fiona Beaty, who led the research as part of her PhD dissertation at the University of British Columbia, said she selected the whelks (also known as a winkle) because her team anticipated that it would be vulnerable. But the more she connected the dots, the more she said the message “emotionally hit home.”

“It's pretty intense to get these results and connect them with the fact that the beaches I grew up with are probably not gonna look the same if I have kids or grandkids,” she said.

“And that's sad. That's part of climate change. We're like letting go of these ecosystems that we're deeply connected with.”

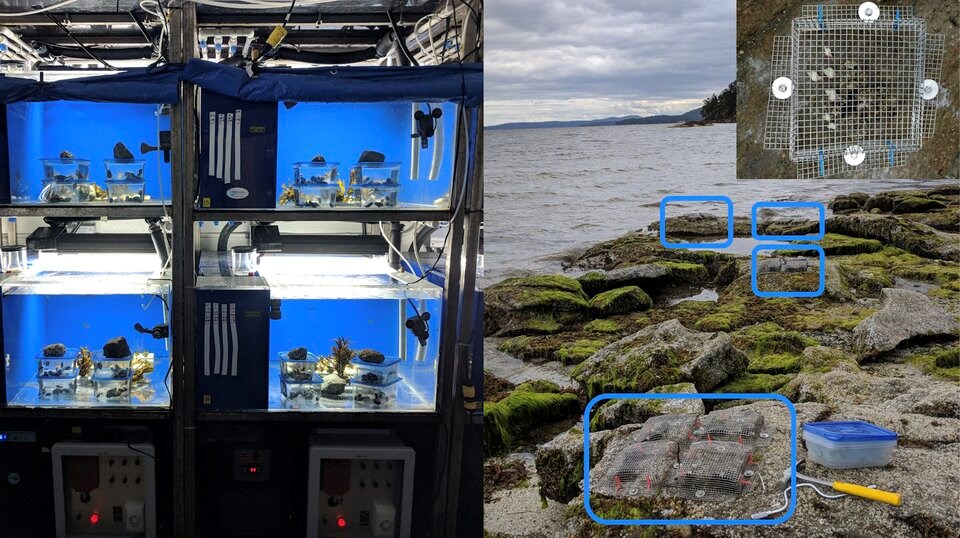

Beaty and her UBC colleagues did two experiments: one in the field to understand how snails are coping now and another in the lab to test how they will respond to future warming.

For the field study, the group installed cages filled with the sea creatures at four shoreline locations, two on Calvert Island and two south of Nanaimo.

Next, they used long-term sea surface temperature data collected at the nearby Egg Island and Departure Bay lighthouses, as well as more recent satellite data, to estimate peak summer temperatures the snails would likely face in both coastal locations.

Back at a UBC lab, Beaty and the other three scientists exposed 200 snails to four water temperatures over six weeks. Those included a 12 to 15 degrees Celsius summertime range currently found on the Central Coast; the 15 to 19 C water temperature range found in the Strait of Georgia; as well as the 19 C and 22 C researchers expect in the two coastal locations under a future warming scenario.

By the end of the lab experiment, 10 per cent of the snails in the Central Coast scenario had died. But in the Strait of Georgia group, mortality spiked to 50 per cent. Results from the shoreline cage experiment weren’t far off, Strait of Georgia snails had a survival rate up to 34 per cent lower compared to their northern relatives.

“This alignment between laboratory and field results suggests that Strait of Georgia snails are stressed in their current environment and vulnerable to future warming,” noted the study.

Dogwhelks range from Central California all the way up to Alaska, but the hottest seawater conditions are expected to be found in the Strait of Georgia, said Beaty.

Protected from the Pacific by Vancouver Island, the enclosed water body gets topped up with relatively warm layer of Fraser River water as if it were a summertime marine bathtub.

“We might see kind of like a gap in their species range and some sort of like local extinction, because populations to the south and Washington can't recolonize this body of water,” Beaty said.

The disappearance of dogwhelks would almost certainly have a ripple effect up and down the food chain, says the scientist. The predatory snail helps keep barnacle and mussel populations in check, and forms an important food source for sea stars, birds and crabs.

Their absence could also make room for the explosion of other species more suited for warm waters. Pacific oyster, an invasive species brought over by ships from subtropical East Asia, could increasingly hitch a ride and compete with mussels to dot rocky shores with their white shells.

“That has implications for shorebirds which feed upon mussels preferentially,” said Beaty. “We're already seeing a decline in a lot of shorebirds.”

The results of the study offer a glimpse of the early impacts of future ocean heating. By mid-century, moderate climate warming is projected to raise the region’s sea surface temperatures beyond 22 C the snails endured in the experiment, and above 25 C by 2100 — a potential death sentence for the Strait of Georgia population.

Extreme weather events could further accelerate those changes. During and after a record heat wave in 2021, Strait of Georgia dogwhelk snails experienced among the highest death rates along all of B.C.’s seashore creatures, according to unpublished research from UBC’s Chris Harley, the supervising researcher on the study.

In 2022, Harley told Glacier Media the extreme event may have primed B.C.’s southern waters to resemble the subtropical East Asian coastlines of Korea, China and southern Japan.

“Things die back, that makes way for oysters,” Harley said at the time.

“I think our system is going to turn into this strange stew of things that we're used to, and things would have shown up from across the ocean that just evolved in a warmer climate.”

While it’s hard to pin down exactly how the complex interactions will play out, Beaty says “we can definitely anticipate” there will be “lots of turbulence” in the region’s future.

“My instinct is less biodiverse,” Beaty said.