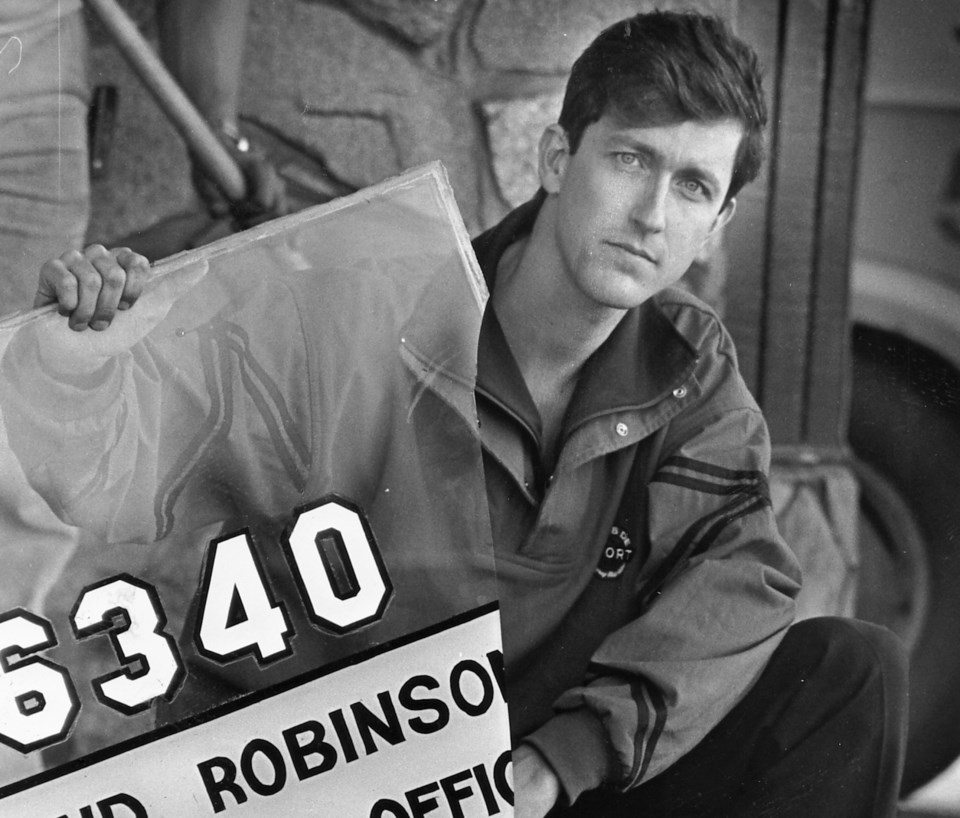

When Svend Robinson, Canada’s first openly gay member of parliament, was in his first term as MP of Burnaby, he was approached by a Burnaby mom concerned about her son.

Her husband was a major in the Canadian Armed Forces and her son, an air cadet, had dreams of becoming a military pilot, but she had heard Robinson speak about discrimination against gays and lesbians in the military.

“I remember it so vividly,” Robinson said. “She said, ‘My son would love to be a pilot in the military but he’s homosexual, he’s gay. What can we do?’ And I had to tell her, ‘Look, I’m sorry. This is the way it is right now.’”

From the 1950s to the early 1990s, the Canadian government not only discriminated against gays and lesbians in the military and public service, it rooted them out in order to fire them.

The rationale was that non-heterosexuals were at a greater risk of blackmail by Canada’s enemies because of what was then called “character weakness.”

“This thinking was prejudiced and flawed. And sadly, what resulted was nothing short of a witch-hunt,” Prime Minister Justin Trudeau said in an official apology in the House of Commons Tuesday.

Robinson was in Ottawa for the apology and called it “truly a historic day.”

About 60 victims of the decades-long so-called “gay purge” watched the apology from the gallery, he said.

“For them to hear from their Prime Minister, and not just from their Prime Minister, but the leaders of all the parties, ‘we’re sorry, it was wrong’ and – just as importantly – 'never again,' it was incredibly moving and powerful,” Robinson said.

As a member of an advisory council to the Prime Minister, the former longtime Burnaby MP had helped craft the apology along with a diverse group of gay, lesbian, transgender and two-spirit (LGBTQ2) people from across the country.

“He reached out, and I was honoured to have been asked to do that,” Robinson said.

Along with the apology, Trudeau announced $145 million in funding Tuesday for reparations to victims and for memorialization and awareness raising projects as part of a class action lawsuit settlement.

A new bill introduced Tuesday will also enable the records of those criminally convicted for same-sex acts in the years when they were illegal to be expunged.

“For me the most important thing was that it not just be words but that there also be an acknowledgement of pain and the human cost that this took, the human toll that this took and that the apology should be accompanied by meaningful redress,” Robinson said. “There has to be funding – and this has been agreed – for research and for awareness, because most Canadians have no idea that this happened. They remember Pierre Trudeau almost 50 years ago saying, ‘The state has no place in the bedrooms of the nation,’ but they have no idea that for 30 years after that people were being discriminated against, persecuted, in some cases taking their own lives, criminalized.”

Robinson said that story needs to be told and the government documents related to it released.

“An important part of this apology process is a commitment to do that,” he said, “I fought for years to get access to documents so that the truth is told about what actually happened.”

When Robinson graduated from Burnaby North Secondary School in 1969, gay sex was still a crime.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms didn’t exist until three years after he was first elected, and section 15, which has successfully been used to oppose discrimination based on sexual orientation, wasn’t brought into force until 1985.

Robinson said coming out publicly as gay during his early years in politics was a non-starter.

“From the time I was nominated and beyond, I knew that one day I hoped to be able to be open, but back then, if I had just come out right away, before people knew me, it would have been the end of my political career,” he said. “I had to lay the groundwork for it.”

After he came out in the spring of 1988, he would remain the only openly gay MP until 1994, when Bloc Québécois MP Réal Ménard came out.

(The first woman to come out as lesbian in the House of Commons was NDP MP Libby Davies in 2001.)

“I used to joke I didn’t exactly start a trend, did I?” Robinson said with a laugh. “There was a lot of fear still. When I came out initially, my office was trashed on Kingsway. Premiers – (Progressive Conservative Grant) Devine in Saskatchewan, (Socred Bill) Vander Zalm in British Columbia – were saying ‘This guy is a terrible role model for young people.’ The prime minister in the election six months later, (Brian) Mulroney, was saying, ‘Imagine Svend Robinson as minister of national defence.’ It didn’t exactly encourage other gay and lesbian folks to come out.”

Among the homophobic hate mail Robinson received after coming out was a letter containing a single bullet and a call for him to use it on himself.

“We’ve made extraordinary progress,” he said.